There’s No Time to Glide: Clyde Has Too Much to Do

- Share via

It is the irony of this glamorous sports town that greatness is often too tired to look pretty.

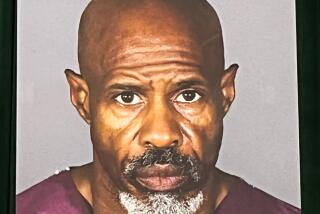

Clyde Turner is like this.

Greatness lives in a lower middle-class neighborhood, has 100,000 miles on its car, twice that many on its shoes.

Greatness works three jobs, chasing kids in the morning, watching them run in the afternoon, coddling them at night.

Greatness makes so little money as a coach, it actually pays for the privilege.

Greatness has won three consecutive state championships, four this decade, yet he says he has not witnessed one moment of any victory.

Greatness is too busy helping others see it.

Clyde Turner, today’s two-minute guy.

You probably have not seen his name until now. You will see it during the 120 seconds it takes to read this story. You probably will not see it again.

Nationally celebrated, locally ignored, the way it always is with people like this.

Clyde Turner, former national track coach of the year, coach of arguably the nation’s best high school boys’ track team, working toward a fourth consecutive state championship.

Clyde Turner, in his 40s, for nearly half his life working a hard dirt track at Pasadena’s Muir High.

He never received his college degree but has coached hundreds who have.

He was never a great runner but has taught hundreds to fly.

In the mornings he is a truant officer at a middle school. In the afternoons he runs the noisy Muir boys’ track program with an assist from five coaches and his wallet.

His phone rings dozens of times each night, but it’s never fame, it’s a kid needing a ride to practice, a sore muscle treated, a full belly for the first time in three days.

Seventy kids each year since he became coach, some of this country’s greatest athletes and neediest children, following Clyde Turner into his brief dreams.

“Sleep is not on my schedule,” he said, and you believe him.

During a recent conversation on the eve of local track sectionals, he took nearly a dozen phone calls from kids and coaches, not to mention a visit from an athlete and his uncle.

The conversation ended at 10:30 p.m., just in time for Turner to drive to the home of Obea Moore, considered this country’s best high school long sprinter.

Moore was suffering from a hamstring injury. Turner had promised to treat the muscle in hopes of allowing him to run the next day.

“That’s why I’ve never seen any of our state championships,” Turner said, laughing. “I’m always in our tent, where somebody always needs something.” Nanette Moore, Obea’s mother and vice principal at Duarte High, made it clear this visit was not unprecedented or even unusual.

“Clyde has a true love for it,” she said. “This team is like his family.”

That’s what greatness builds, families, who grow larger and closer, and doesn’t Turner know it.

On football weekends, while many high school coaches are glued to the TV, Turner is glued to that phone.

He has served as the track coach for nearly a dozen current college or NFL players who call him to request a five-minute pep talk.

Maybe the one about the predator versus the prey. Or the one where he spins memories, reminding the athlete not to forget his roots.

Chad Brown. Marcus Robertson. Darick Holmes. All have called, always on Sunday mornings, just as they get into the locker room.

“When Ricky Ervins was with the Redskins, he would call at 7 a.m. our time and say something like, ‘We’re playing the Cowboys, what do you think?’ ” Turner said.

Turner thinks track can teach a focus that can be used in other aspects of life. He thinks track can be worth $120,000 to a child if that focus is on a scholarship.

He also thinks that even if Muir wins another title in a couple of weeks in Sacramento, the team cannot give him what it did in 1995.

In a span of three weeks that spring, Turner lost his mother to diabetes complications, his assistant coach to a drive-by shooting, his uncle to a heart attack.

And three of his top track stars could not participate in the state meet because of personal or academic problems.

On the day of his mother’s death, which occurred on the eve of the meet, he gathered his team in a Muir classroom. From behind darkened glasses, he explained the troubles and told them that this time, their inspiration would have to come from within.

He then excused himself, but a funny thing happened.

His team would not let him go. The boys surrounded him, all 70 of them, engulfed him in a group hug, promised to win the state meet to remind him of his strength.

So they did, which was greatness in itself, which is why it’s OK to forget all about Clyde Turner now, why he won’t even notice.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.