To the Manner Born, Bush Finds His Own Way

- Share via

HOPKINSVILLE, Ky. — It’s nearly noon. The sun is hot.

Since an early-morning flight from Austin, Texas, George W. Bush already has given a speech to senior citizens and sat through an hour’s bus ride crammed with local news interviews. He still has autographs to sign here at the Wood House barbecue shack, then a tour of the Corvette plant and an airport rally in nearby Bowling Green.

Yet Bush is working three or four hundred yards of rope line as though it were a dip in the pool. Unhurried, visibly exhilarated, he shakes hands and banters with the crowd, hydroplaning on the moment.

“That your son-in-law?” he asks a middle-age woman. “How’s he behaving? Doing everything you tell him?”

“Who you got there?” he asks a man holding a child. “She’s a lot better looking than you are.”

An arm goes around a soldier leaning against the rope. The gesture, close but not too close, conveys both warmth and respect for the uniform. An aide takes the soldier’s small camera, snaps a picture and smoothly returns the camera as the candidate moves on.

Leaning down to a boy standing with an older man, Bush says, “You listen to your granddad. He’ll give you some good wisdom.”

Along the side of the parking lot, all the way to the highway out front, he is a natural, seemingly lost in the pure pleasure of the act. It has been a long time coming, but George Walker Bush is free at last.

Free at last because, until recent years, the course of Bush’s life was marked by long, looping curves that sometimes took him far away from his destination. Most political leaders plunge into their careers right away. But Bush was like the hero of an old story who wants one thing but first must accomplish something else--slay a dragon or retrieve a treasure.

Only now, at age 54, is he finally doing full time what the evidence suggests he wanted all along: to have a life in national politics.

Politics has always been the magnet that tugged at his compass: From the playground leader and big man on campus of his youth through brief but telling campaign experiences as a young man, the hints of an unquenchable appetite--and substantial gifts--were there. Now, as he prepares to claim the Republican presidential nomination, he clearly has emerged as a skilled practitioner of the political arts.

Some still deride him as an “empty suit,” but it takes more than a famous name and a bankroll to dominate the early phases of the nominating process, roll over a flock of challengers, take a knee-buckling punch from Sen. John McCain of Arizona and sweep to victory.

With such a lifelong itch--and with politics woven deep into his pedigree--why did it take him so long to find his calling? Why did he devote most of his adult life to a middling career in business? Why has the man who may become the 43rd president of the United States served in government only as governor of Texas for the last six years?

The answer speaks to the central, enduring struggle of Bush’s life: the need to reconcile the tradition-bound standards and expectations of his father and grandfather, men he reveres as heroes, with his own more freewheeling and impatient nature.

The Bush family credo was laid down by his grandfather, the late Sen. Prescott Bush of Connecticut. By both word and deed, he declared that in pursuing his career, a man’s first duty was to secure a fortune and provide for his family. Then, in the spirit of noblesse oblige, he might turn to public service.

The sequence was all important. A politician who had not made himself independently wealthy might be tempted to compromise his principles, might be too eager to please the crowd.

It was a dictum that George Herbert Walker Bush, the senator’s son and future president, followed to the letter. It fit both the man and his times. Not so for George W. Bush. Yet the fact that the prescribed course had been embraced by his father gave the tradition enormous power. It sent his own life on a decades-long digression that ended only when fortune handed him a chance to own a professional baseball team, the Texas Rangers, which in turn laid the groundwork for his political career.

When Bush talks about his parents, he emphasizes their unequivocal love and willingness to let their children find their own way. But his family’s code was enforced not so much by words as by the sterner command of silent expectations.

Only rarely would Bush’s dad spell it out. There was the summer during George W.’s college years that he took a job as a roughneck on an oil rig, only to give it up when he found the offshore assignment too confining.

“I was called to my father’s office in downtown Houston,” Bush recalled in an interview. “He simply told me: ‘In our family and in life, you fulfill your commitments. You’ve disappointed me.’ ”

Long afterward, when his father labored in the shadow of Ronald Reagan, many Americans saw the older Bush as decent but ineffectual, dogged by what a newsmagazine cruelly called “the wimp factor.” But to his family, especially his oldest son, Bush the elder was always a towering figure, the gold standard of how a man should live his life.

Among his detractors, the younger Bush’s career is commonly portrayed as a corner-cutting version of his father’s--superficially parallel, but with the hard parts left out. “Bush Lite,” insiders joke.

That’s a misleading portrait. A man with a needle-sharp sense of humor and an itch to skate near the edge, George W. Bush has shown a remarkable ability to survive in tough competition, learn from experience and get where he wants to be, regardless of detours.

Now, as he prepares for the last leg of his quest for the White House, Bush displays the serenity of a man who has the treasure tucked securely beneath his arm.

“I don’t know where my life is going to end up, and I don’t fear not knowing where my life is going to end up,” he said recently. “I know I’m going to end up in the grave . . . so I’m going to live life to the fullest. I want the chapter book to be full.”

Myth and Legend Texas vs. the East

When he talks about the influences that shaped him, Bush emphasizes growing up in Texas. The difference between himself and his father, he’ll say, is that “he went to Greenwich Country Day School [in Connecticut], and I went to San Jacinto Junior High” in Midland, Texas.

San Jacinto. The name echoes: the battle in which Mexican Gen. Santa Anna was routed, the Alamo avenged, Texas made free. The land that is home to tough, bootstraps people who can spot a phony quicker than a tornado and never run out on a friend. Football-crazy on Friday nights, churchgoing on Sunday, back to work Monday--early.

This is where the myth begins.

Young George W. Bush attended San Jacinto Junior High for exactly one year. Even if you add the preceding six years at Sam Houston Elementary in Midland and a subsequent two years at the exclusive Kincaid School in Houston, the total is no greater than the nine years back East at Phillips Academy, Andover, Yale and Harvard.

But remember: Myth is truth in costume.

Bush is right when he says, “I think I remained more closely part of the world I grew up in. I was educated up East, but my heart was always back in Texas. . . . I could have chosen to remain in the East, but I love Texas, have great pride in Texas and everything Texan.”

His Texas childhood was rich in traditional values and normalcy. Little League. Baseball cards. Dads who worked; moms who stayed home. Neighbors who kept an eye on each other’s kids. Back-fence pals who became friends for life.

Yet Bush was always set apart: First among equals, confident heir to something larger than Texas. In a circle of adults making fortunes, his father was always among the most successful, his parents the most prominent in church and community. His was the house with the pool. Headquarters for the neighborhood gang.

Always, it seems, Bush was recognized as the leader of the pack. First to launch the next adventure. Quickest with a nickname or wisecrack. Always the most daring and irrepressible.

Moreover, within his childhood circle none possessed such an ancestral line, a well-tended link to the aristocratic Bush and Walker clans in the East. It was a heritage of established wealth and influence, as well as public service, that molded the child’s inborn sense of primacy and forged the legs on which he stands for president.

It was also a heritage that imposed inescapable expectations.

When he entered the world on July 6, 1946, spurred by a dose of castor oil his impatient Bush grandmother administered to his mother, his parents’ life resembled an old movie starring Cary Grant or Walter Pidgeon, Katharine Hepburn or Greer Garson.

Bush’s father, admired as a student and a baseball player when he graduated from Andover, had brushed aside parental objections and enlisted in the Navy--on his 18th birthday, June 12, 1942.

At a Christmas dance six months earlier, he had met a 16-year-old girl named Barbara Pierce. They dated, exchanged letters and, soon after he became the youngest pilot in the Navy, announced their engagement. Then he shipped out to the South Pacific.

It was a story out of Life magazine. The tall, handsome pilot from a prominent family. The wartime romance. His plane shot down over enemy waters. Rescued by submarine. Coming home a hero, with three Air Medals and the Distinguished Flying Cross. George and “Bar” were married just after New Year’s 1945.

When the war ended, Bush entered Yale. Like many returning veterans, he was more mature, more purposeful than the younger students. He was fraternity president, member of Skull and Bones--Yale’s most legendary secret society--and Phi Beta Kappa, all in three years.

He was also star first baseman of the team that won the Eastern Intercollegiate championship two out of his three years. Bar went to all the games and kept a score book even when pregnant with her first son.

The future president’s subsequent decision to pack his red Studebaker and head for Texas and the oil business in 1948 only added to the legend: Shunning the easy life on Wall Street, learning a risky business from the ground up, doing his family proud with an entrepreneurial triumph--and only afterward turning to politics.

That was exactly how Prescott Bush had said it should be done.

But the decision to go West was not quite the leap into a night sea that it might seem.

For generations, the sons of old money in the East had sallied forth to new-money hot spots in the West. When the rich range land of the Dakotas opened up in the late 19th century, so many of Theodore Roosevelt’s Ivy League peers joined him in ranching that Tiffany & Co., the New York jeweler, produced the ornate bronze belt buckles favored by the cowboy aristocrats.

Similarly, when George H.W. Bush moved to Texas with his wife and young son in the late 1940s, the oil business was booming and he was far from the only Yalie drawn to the Permian Basin’s promise of sudden wealth.

He went, the future president told Fortune magazine, because he wanted to avoid “cut-and-dried jobs, with everybody just like everybody else, getting a job with Dad’s help and through Dad’s friends.”

In reality, the oil field supply firm that hired him in Odessa, Texas, was a subsidiary of Dresser Industries. Prescott Bush sat on Dresser’s board, and his son’s job had been recommended by his good friend, the company’s president.

Those details were beyond the ken of a 2-year-old boy, of course. And they would not have mattered anyway; his father and grandfather were already the commanding figures of his life.

And he always understood that members of families such as his lived on a different plane. One of the things that later irritated him about Ivy League liberals was that they seemed to feel guilty about being born to privilege.

Texas Roots

Life in Odessa was colorful. The postwar housing shortage was so acute that the little family moved into part of a tiny house on an unpaved road and shared the bathroom with a mother-daughter team--prostitutes, legend has it. The Bushes were lucky at that; most of their neighbors lacked indoor plumbing.

The senior Bush was gone from morning to night, working in the company warehouse, traveling the oil patch, learning the business. After Odessa, there was a similar year in Bakersfield, Whittier and other California oil towns.

Another child might have found the continual moving and the unfamiliar people unsettling; Georgie seemed to thrive.

With the father gone and relatives far away, mother and son were thrown together in a relationship that would be different from Barbara’s relationships with her other children--close, but turbulent and demanding too.

The Bushes’ second child, a girl, was born in Compton in December 1949. They called her Robin.

By 1950, his apprenticeship over, the senior Bush’s company rotated him back to Texas. This time he settled his family in Midland and within a few months started his own business buying and developing oil leases. Unlike blue-collar, roughneck Odessa, Midland was home to managers and entrepreneurs--middle-class, solid and strict. “Raise hell in Odessa, raise a family in Midland,” people said.

The Bushes paid $8,000--no small sum then--for a house in a new subdivision known as Easter Egg Row because each house was painted a bright but different color. In many ways, life there had a Technicolor quality too. Young George went to Sam Houston Elementary. Both parents taught Sunday school at First Presbyterian. The senior Bush was into everything, from the YMCA and Community Chest to breathing life into the local GOP.

The senior Bush and his partner brought in scores of high-yield wells, then morphed it into Zapata Oil. With his family helping line up funds, Bush pioneered offshore drilling. By 1954, he was a multimillionaire.

His son, meantime, lived in a world presided over mainly by his mother. She was the disciplinarian; she had the hot temper. And, while another son, John E. “Jeb” Bush, had been born in February 1953, she targeted her maternal wrath most often at the impish Georgie.

He had her quick tongue. He was not shy. And as sometimes happens when a first son is several years older than his nearest brother, he saw himself as a junior peer of his parents.

“I don’t think I was a difficult child, but I must have been pretty strong-headed,” he said. “There were rules. One of them was children are to be seen and not heard, especially around adults. I must have violated that one all the time.”

He chuckled, recalling the time his father wrote a friend, “Georgie annoys the hell out of me talking dirty.”

In school, Georgie was the one who put a football through a window. Outside class, baseball consumed his life. He played Little League, with his mother always in the stands as she had been for his father. It was clear the boy would never match his father’s skill, but he had the grit to play catcher.

Into the midst of all this innocence came tragedy.

In March of 1953, 3-year-old Robin Bush was diagnosed with leukemia. At the time, the disease was so uncommon her parents had never heard of it. Unlike today, when many children recover, it was invariably fatal.

The senior Bush called his uncle, Dr. John Walker, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital in New York. He confirmed the grim prognosis but offered treatment that might buy time--for a breakthrough or a miracle. The parents and their daughter flew to New York at once. Six-year-old Georgie and baby Jeb stayed behind, unaware of their sister’s condition.

For six months, the parents shuttled between Manhattan and Midland, sometimes using a private airplane lent by their friend Eddie Chiles, who years later would play a pivotal role in George W.’s life by selling him the Texas Rangers.

The medical team tried everything. But on Oct. 11, Robin died. Her stricken parents went home to Midland to break the news to their sons.

George was outside his school when his parents’ car appeared. “My mom and dad and sister are home!” he shouted to a teacher. “Can I go see them?” He raced to the car, thinking he saw Robin. “I got to the car still certain Robin was there, but of course, she was not,” he said later.

“We felt devastated by what we had to tell him,” Barbara Bush wrote in her memoirs. “As I recall, he asked a lot of questions, and couldn’t understand why we hadn’t told him, when we had known for such a long time.”

For parents, it was the wound like no other. Eventually, Barbara dealt with the pain by plunging back into community work. Initially, as she and others have described it, she who had been the rock during Robin’s illness now almost crumbled. For a time, she leaned on Georgie.

When he came home from school, she would be his constant companion. Intentionally or not, he would help her deal with some of the sources of pain.

For one thing, after the initial round of condolences, a veil of silence descended. Outside the family, no one mentioned Robin and her death. Well-intentioned as it was, it made the anguished parents feel as though their daughter had never existed.

Georgie, his mother said later, tried to punch a much-needed hole in the curtain. On one occasion, father and son were sitting in the stands at a football game with friends when Georgie announced, “I wish I were Robin.”

The adults froze. Why? his father asked. “I bet she can see the game better from where she is than we can here,” came the answer.

Some months later, Barbara suddenly realized how much she was relying on her older son. She overheard him tell a friend he would like to play but had to stay with his mother. “That started my cure,” she wrote later. “I realized I was too much of a burden for a 7-year-old boy to carry.”

A little over a year after Robin’s death, Neil Bush was born, followed in 1956 by Marvin. (Dorothy, the final child, was born in 1959.)

After Neil was born, the family decided they had outgrown Easter Egg Row. They moved to a larger house that had a swimming pool. They got a puppy. The new house and their lives were again filled to bursting with kids, sports and community doings.

They lived there four years; then, in 1959, the senior Bush’s business success, as well as his ripening political plans, dictated a move to Houston.

For Georgie, the year at Midland’s San Jacinto Junior High was followed by two years at Houston’s Kincaid School; the difference in names told the story. He didn’t know it, but George W.’s idyllic Texas childhood was about over. It was almost time to go “up East.”

Andover and Yale: Boxing the Compass

Early in his father’s oil career, an old hand remarked that he seemed to be a college man. Yale, Bush replied. The man thought, then replied sympathetically, “Never heard of it.”

Much as the elder Bush tried to embrace Texas mores, when it came to education, people like that didn’t count. His oldest son would go to Andover and on to Yale--these were critical steps in training the man he was meant to become.

Houston is 1,858 miles from Boston, but that’s not why Bush remembers Andover as “a distant land.” In 1961, the great New England boarding schools were still cold and forbidding, committed to the spartan values on which they were founded. High standards set, hard work expected, scant emotional comfort offered.

“It was hard. It was really hard,” Bush said recently.

How Bush responded to the challenges at Andover and Yale offers an early clue to the way he has tried to box the compass of his life: finding a way to honor his father’s heritage, even though he was a different person and was growing up in an age beginning to scorn the old traditions.

Bush could not match his father’s record as a scholar or an athlete. His grades were mostly middle-of-the-pack. By his senior year, when a counselor noticed he was applying only to Yale and the University of Texas, he urged Bush to think of fallbacks. As an athlete he had more moxie than talent.

What he would use to make a place for himself was his exceptional social skills--the skills of a politician. “My ability to make friends,” Bush calls it. “It’s just who I am. I can make friends well.”

In fact, some of Bush’s closest confidants today are friends from early in his life, including Midland pal Don Evans, general chairman of the presidential campaign, and Clay Johnson, his chief of staff in the governor’s office, from Andover and Yale days.

Andover classmates have remembered him the way grade school friends did, as an informal leader who was fun to be with, the one who came up with zany ideas and funny quips. In a setting that put a premium on adolescent sarcasm, Bush had no trouble earning the nickname “Lip.”

It helped that he was not afraid to make himself conspicuous: Some recall him tweaking the school’s dress code by wearing a tie with a T-shirt.

Unable to be a sports star, he became head cheerleader at the then-all-boys school. And he pulled the cheering squad into the modern era in a way that set his peers laughing and school elders tut-tutting.

At football games, biographer Elizabeth Mitchell wrote in her book, “W: Revenge of the Bush Dynasty,” he wielded a giant megaphone like a stand-up comic, with barbed comments about players and spectators. At Saturday morning assemblies, his cheerleaders put on skits, appearing once as a motorcycle gang and another time in drag.

Faculty members grumbled that the cheerleaders were starting to overshadow the team. But the school paper came to their defense, saying: “George’s gang has done a commendable job, and now is not the time to throw a wet blanket over cheerleading.”

By graduation day in 1964, Bush had gotten into Yale. Perhaps the counselor had forgotten his father was a distinguished alumnus and his grandfather a trustee of the university.

College in many ways was just a continuation of Andover, with drinking added. Bush got to know a lot of people, made friends with most of them and led a social circle that seemed to have more rollicking good times than just about anybody. He joined his father’s old fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon, known for the biggest and best parties, and became its president too. He also followed the family path into Skull and Bones.

Bush majored in history and did well enough--as well as his more studious-seeming Democratic rival, Al Gore (two years his junior), did at Harvard, as the press would later report.

And, during his freshman year, Bush got his first real taste of political campaigning in his father’s hard-fought Senate race against liberal Texas Democrat Ralph Yarborough. Through the summer before college, he had listened as his father and his top aides plotted strategy over Sunday afternoon cookouts--sessions that emphasized grass-roots organizing over ideology.

Young Bush traveled the state with his father too, tasting the excitement of building support among conservative but traditionally Democratic voters. On election night, he was at the tote board, recording his father’s narrow defeat--but also observing his resilient determination to try again.

Not long after the vote, the gregarious freshman introduced himself to Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, already an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War but also a contemporary of Bush’s father and fellow Bones man. “I know your father,” Bush remembers Coffin saying. “He was beaten by a better man.”

It was a brutish remark. “You talk about a shattering blow,” Barbara Bush later told her biographer, Donnie Radcliffe. “It was a very awful thing for a chaplain to say.”

The bruise lasted a long time, partly because it struck at the heart of the profound problem Bush’s college years presented:

Outwardly, he was drinking life to the lees--often literally--seemingly without a care. But beneath the surface, history was beginning to put him in a bind.

In Bush’s view, the great social and political protests that engulfed colleges in the late 1960s and early ‘70s hit Yale in full force only after he graduated. “The guys behind me in college became the hair people,” he said this spring.

But by his senior year in 1967-68, the tumult on his campus and others was building. The problem for Bush was not just that he could not join the protest movements; he did not share those views, and it would have been an unimaginable repudiation of his family anyway. The problem was that he could not escape membership in his generation either.

That would become painfully evident when he confronted the questions of military service.

Wild Oats

On Feb. 16, 1968, early in a year that would see conflict over the Vietnam War turn violent and the Democratic Party tear itself to pieces at its Chicago convention, the federal government abolished the draft deferment for students attending graduate school. For many, that precipitated a crisis, but not for 21-year-old George W. Bush. He was already on his way into the Texas Air National Guard.

In January of 1968, he had taken and passed the officer qualification test. That summer, after graduation, he went through an abbreviated form of basic training and received an unusual, direct appointment as a second lieutenant. He would go on to pilot training, learn to fly fighter jets and complete his military service with monthly Guard activities at home in Texas.

Then and later, he couched the decision to join the Guard in terms of wanting to follow in his father’s footsteps as a pilot. He would strenuously deny that he sought to avoid combat in Vietnam or that family influence was used to facilitate his Guard career.

No evidence has surfaced to dispute his statement that neither he nor his father, by then a member of Congress from Houston, sought preferential treatment for him. Still, once in the Guard, Bush moved ahead with exceptional dispatch and without meeting all the time-consuming requirements for advancement and pilot training that normally applied.

Bush also sought and received permission to take part in two political campaigns while he served in the Guard--both far removed from Texas and indicative of where his interests lay.

In 1968, he went to Florida to help conservative challenger Ed Guerney upset LeRoy Collins for the Senate. In 1972, he worked as political director in former Postmaster General Winton “Red” Blount’s ill-fated Senate bid in Alabama.

The itch for politics would not go away.

The campaign digressions, like his admittance into the Guard, have kept alive the questions about favored treatment. Regardless, Bush successfully completed a yearlong pilot training course in which about half the students washed out. And the achievement of learning to fly an unforgiving military jet was all his own: The airplanes had no idea who his father was.

Still, while outwardly following in his father’s footsteps, he sidestepped the part about actually going to war. If pressed on that, Bush will acknowledge he had a choice, that he could have positioned himself to see combat in Vietnam.

“I was prepared to do it,” he said, “but no--if I’d wanted to, I guess I would have. It was in my control.”

If Bush’s attitude toward combat was different from his father’s, so were the war and the times. Rare indeed was the college graduate who rushed to combat in 1968.

In any case, after Bush finished flight school and was transferred back to Texas to fulfill the remainder of his military commitment piecemeal, the Guard was no longer a full-time job. And the challenge of commencing his adult life seems to have caught him unprepared, or at least reluctant to accept what was expected of him.

At first all went well; it was 1970 and his father was running for the Senate again. Young Bush jumped into the campaign, traveling the state as a surrogate and organizing rallies. The experience was doubly important to the younger Bush: Throughout his life, political campaigns--and baseball--allowed him to share his father’s life in ways nothing else did.

Much as it meant to him personally, the campaign took an unexpectedly negative turn: Instead of a chance to unhorse Ralph Yarborough, whose liberal star was fading, Bush senior found himself facing Lloyd Bentsen, a millionaire businessman with solid ties to conservative Democrats.

As George W. had on election night in his father’s previous campaigns, he chalked up the returns as his father was beaten, 53% to 47%.

After that, the senior Bush moved to New York as President Nixon’s ambassador to the United Nations, followed by a turn as Republican National Committee chairman while the Watergate scandal unfolded. Back home, his eldest son held a succession of jobs.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and I wasn’t going to do anything I didn’t want to do,” Bush said. One thing was certain: The coat-and-tie routine “wasn’t for me.”

Things came to a head one night in 1973: Bush had taken his younger brother out drinking during a visit to Washington; returning to his parents’ home, the car had a noisy encounter with trash cans. When his father summoned George W., the son offered to duke it out.

The upshot was twofold:

George W. went home to work with a mentoring program that tried to help underprivileged kids in Houston. And that fall, he entered Harvard Business School, to which he had applied without telling his parents. Again, it seemed, grades weren’t everything when it came to Bush gaining admittance.

He was back on the family track, though he wore his National Guard pilot’s jacket and chewed tobacco in silent protest. With none of the corporate thirst that usually accompanies it, he earned the world’s most coveted MBA.

But what few acknowledged during the seemingly directionless period in Bush’s life--and which he himself may have only vaguely sensed--was how much flight time he was accumulating on the campaign trail. In Florida, in Alabama, in his father’s efforts to build a Republican Party and run for office in Texas, the business young George was learning from the ground up was the business of politics.

Going Home to Texas

No matter these interests, it was a fortune-building career in business that he was expected to pursue. He “needed to get on with making a living,” as his mother wrote.

Stopping in Midland to visit friends, Bush found the oil industry booming; the 1973 Arab oil embargo had sent prices skyrocketing. “It was exciting to me. I was inebriated with the atmosphere out there,” he said.

It was almost exactly how his father had begun and it seemed to promise a relatively painless road to the requisite riches. Bush served a brief apprenticeship, then went into business for himself. He raised some capital through family connections and began to invest modestly in leases and exploration.

On the personal side, life combined the best of his fighter-jock days with something like a return to San Jacinto Junior High. He called himself “Bombastic Bushkin” and was again the funniest, most daring, most raffish member of the crowd.

The legend from this period has the poignant quality of a wild pony trying to learn to love the bridle:

Bush had a tiny apartment that would reputedly have embarrassed a teenager; a welter of shucked-off clothing, old newspapers and a broken-down bed lashed together with old neckties. Often before dawn, he was at the high school track, running laps and--so one story goes--occasionally yanking down the shorts of a much older and slower runner as he swept past.

Running reflected the seemingly contradictory habits of partying hard--sometimes too hard--in the evenings, but going to bed early and rising with the sun. (Even at the height of his drinking, he says, “I was always the first one to go to bed. All my friends will tell you that.”)

Then, quite suddenly, in 1977, his life seemed to turn a corner. He got married and he decided to run for Congress.

His romance with Laura Welch has become a storybook tale--how friends brought them together for a cookout; how the couple seemed to strike sparks at once; how they were married just three months later, in November 1977.

The two had grown up and attended the same schools in Midland, but they had not really known each other. It was not hard to see why. Compared with the brash, impulsive Bush, Laura Welch was quiet and serious, a librarian by training who shunned the spotlight he craved.

It turned out that each offered the other a missing piece.

“I don’t give George advice,” Laura once told the Dallas Morning News. “I know George has plenty of people who want to tell him things. I don’t need to be one of them.”

For his part, Bush says his wife respects his political competence but is worth listening to when she does offer opinions. “She has a lot of common sense. I trust her judgment, probably a lot more than she knows.”

Perhaps most important, “she’s a very calm person.” He remembers how Laura developed toxemia when she was carrying their twin daughters, Jenna and Barbara, in 1981. Bush was very anxious. “Don’t worry,” he remembers her telling him, “the children will be born healthy”--and they were.

After his wedding, Bush launched immediately into the campaign for Congress.

He had only been in Midland a couple of years and had not achieved anything like the financial success family tradition dictated. But Democrat George Mahon, who had represented the district since 1934, was retiring. What happened next was a lesson Bush never forgot. He went into the race cocky as always, and he won a tough GOP primary. Then he met a canny Democratic state legislator from Lubbock named Kent Hance.

As Bill Minutaglio describes the campaign in “First Son,” his biography of the Texas governor, Hance took everything Bush had to be proud of and turned it against him: his education, his family background, even his dedication to running. In every way, Hance suggested Bush was not a legitimate Texan.

Says Bush: “He out-countried me. He created a doubt in people’s minds about my authenticity.”

It began with Bush’s early television spots, which featured pictures of him jogging. A Hance surrogate promptly remarked that in Lubbock, the district’s largest city, the only time a man ran was when he had somebody chasing him.

Says Bush now, “Kent Hance gave me a good lesson . . . and it did make an impression on me.” Never again, if he could help it, would an opponent get between him and his own legitimacy.

Against Hance, Bush fought hard, learned a lot, but in the end lost--by about the same margin his father had in the 1970 Senate race. He would read the voters’ decision by the light of family tradition: He would go back to the oil business and try to do it the Bush way.

Purgatory and Beyond

He did try.

Yet the decade following Bush’s run for Congress is marked by a sense of looming crisis. Meeting the family’s expectations meant everything to him, but deep down he must have sensed that what worked for his father would not work now.

Bush has insisted the family did not pressure him, though he admits there was a sense of relief when he enrolled in business school. And it is striking how his mother scarcely mentions him during this period in her otherwise voluble memoirs.

He raised more capital and pushed ahead with Arbusto Energy Corp., named with characteristic humor after the Spanish word for “bush.” He made a living at it, but his father’s rapid success eluded him. For one thing, Bush never had a single-minded preoccupation with accumulating great wealth. “Money has never been a way of keeping score for me,” he says.

Also, the tide that drew him to the petroleum industry had begun to turn. Oil no longer was plentiful in West Texas. Prices were beginning to slip.

By 1984, there were jokes about changing the company name to “El Busto.” Bush was glad to merge with a company called Spectrum 7, which embodied the oil holdings of the Cincinnati-based DeWitt family, longtime friends of the Bushes and--more important, as it turned out--a clan with ties to Major League Baseball.

The deal did not permanently reverse Bush’s business fortunes, but it bought him time. Off the job, the drinking was becoming serious. Beer, bourbon--whichever he chose, he was doing it more. Laura was talking to him about it. He tried to ease back, but it didn’t work.

“I was too disciplined to be a day drinker. I was certainly not drinking heavily every day,” Bush says. “But alcohol began to crowd out my affections.”

In July 1986, he, Laura and a group of friends went to Colorado Springs, Colo., for his 40th birthday. They stayed at the famed Broadmoor Hotel, and, for Bush, the celebration was unstinting. The next morning, when he went running, he realized he had hit the wall.

“I had to make a choice,” he says. From that day forward, he did not touch alcohol again.

The decision was part of a larger change.

The summer before, while vacationing at the family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine, he had undergone a religious experience. The Rev. Billy Graham, a regular summer visitor, had talked to him at length about accepting Jesus Christ as his personal savior, and Bush began to study the Bible with new intensity.

That spring--April 1985--he had also taken part in a Camp David meeting on his father’s 1988 presidential race. Lee Atwater, the young Turk of campaign hardball, had made a pitch to lead the campaign. When George W. raised the question of loyalty--Atwater had ties to potential GOP rivals--Atwater had challenged him to join up as a watchdog.

The religious experience, the invitation to return to politics and the turning away from alcohol all came at a time when Bush’s business situation was becoming untenable. Once more a rescuer arrived when he needed it. A company called Harken Energy Corp. that specialized in picking up foundering oil firms threw Bush a rope. It would take on his company’s debts, give him a substantial chunk of Harken stock and pay him an annual salary to serve as a consultant.

Was it because his father was vice president and Reagan’s heir? Many thought so. But Bush could hardly be blamed for jumping at the offer. He made sure his old employees had jobs, then packed the family off to Washington and his father’s presidential campaign.

Soon, Texas flag tacked to the wall, he was ensconced at Atwater’s elbow. They turned out to be soul mates, hyperkinetic political hipsters who loved the game in all its details.

“The thing I liked about George was that he was willing to do absolutely anything,” one aide to the ’88 campaign recalls. “If there was an event out in [the Washington suburb of] Prince George’s County [and] a local congressman was supposed to speak and canceled at the last minute, you could ask George. And he’d jump in his car and drive through all that traffic and make the speech.”

Another sign of Bush’s growing savvy was that he took the time to listen to emissaries from the Christian right, becoming a link between them and his father. In the process, he learned to deal with what is now a vital part of his own constituency.

It was also during the campaign that Bush got another call from the DeWitt family. Chiles wanted to sell the Rangers, he was told. Maybe he should consider becoming an owner.

The question of what he would do after the campaign had been hovering over his head. This seemed the answer: He loved baseball and, he said, “it was a visible position.”

After his father’s election and transition into the Oval Office, he went home and put the Rangers deal together in April 1989.

The timing had been perfect: As he was leaving Washington, Harken Energy went into a tailspin. Bush sold his interest just before the bad news broke; the Securities and Exchange Commission looked into the question of insider trading but took no action. Bush used the $800,000 he had gained to get into baseball.

Bush ran the Rangers like a political campaign. He had an issue: the need for public financing of a new stadium, which he got. And he used his position to showcase himself almost like one of the team’s stars. He had baseball-style cards printed up with his picture on them, and almost every day throughout the season he could be found in his seat signing autographs and greeting potential constituents.

When he left to run for governor in 1994, he would reap $15 million on his investment. More important, he had established himself as managing partner and public face of a phenomenally successful business.

Almost miraculously, the monkey was off his back. Finally, he could concentrate on what he’d been preparing for most of his life.

In the only game he was ever really good at, George W. Bush could now make the varsity.

With the White House within reach, he might even become an all-star.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

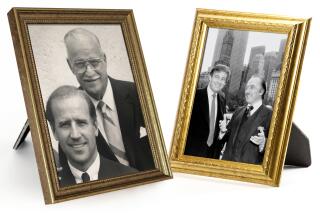

His Major Influences

PRESCOTT BUSH

Bush’s grandfather said life should be approached in this order: first provide for your family; then turn to politics. It was the blueprint followed by both Bush and his father.

*

GEORGE BUSH

A commanding figure in his son’s life, his disapproval could cut like daggers. To George W., his father is the gold standard of how a man should live his life.

*

BARBARA BUSH

She was the disciplinarian. Her relationship with George was different from relationships with her other children--close, but turbulent and demanding too.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

His Early Years

PERSONAL

* Born July 6, 1946, in New Haven, Conn., to George and Barbara Pierce Bush. His father was still a student at Yale.

* Residences: Austin and Crawford, Texas.

* Married 22 years to former Laura Welch. Twin daughters, Barbara and Jenna, age 18.

* Religion: Methodist.

* Hobbies, interests: Running, baseball, bass fishing.

* Pets: dog, Spot; and two cats, India and Ernie.

EDUCATION

* History degree from Yale University, 1968. MBA, Harvard University, 1975.

MILITARY

* Pilot in the Texas Air National Guard, 1968-73.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

His Professional Years

* After working in the Texas oil industry for about two years, Bush formed his own oil and gas company, Arbusto (Spanish for “bush”) Energy Inc., in 1977.

* Ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1978.

* Arbusto merged with another energy company, Spectrum 7, in 1984 and Bush became CEO of the new firm. Harken Oil and Gas bought Spectrum in 1986.

* Served as an advisor to his father’s presidential campaign in 1988.

* Managing general partner of Texas Rangers baseball team, 1989-94.

* Elected Texas’ 46th governor in 1994, reelected in 1998.

* Wrote autobiography, “A Charge to Keep,” (William Morrow & Co., 1999) with communications director Karen Hughes.

*

The Times will profile presumptive Democratic candidate Al Gore two weeks from today, on the eve of the Democratic National Convention.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.