From the Archives: With ‘Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana,’ Umberto Eco considers identity

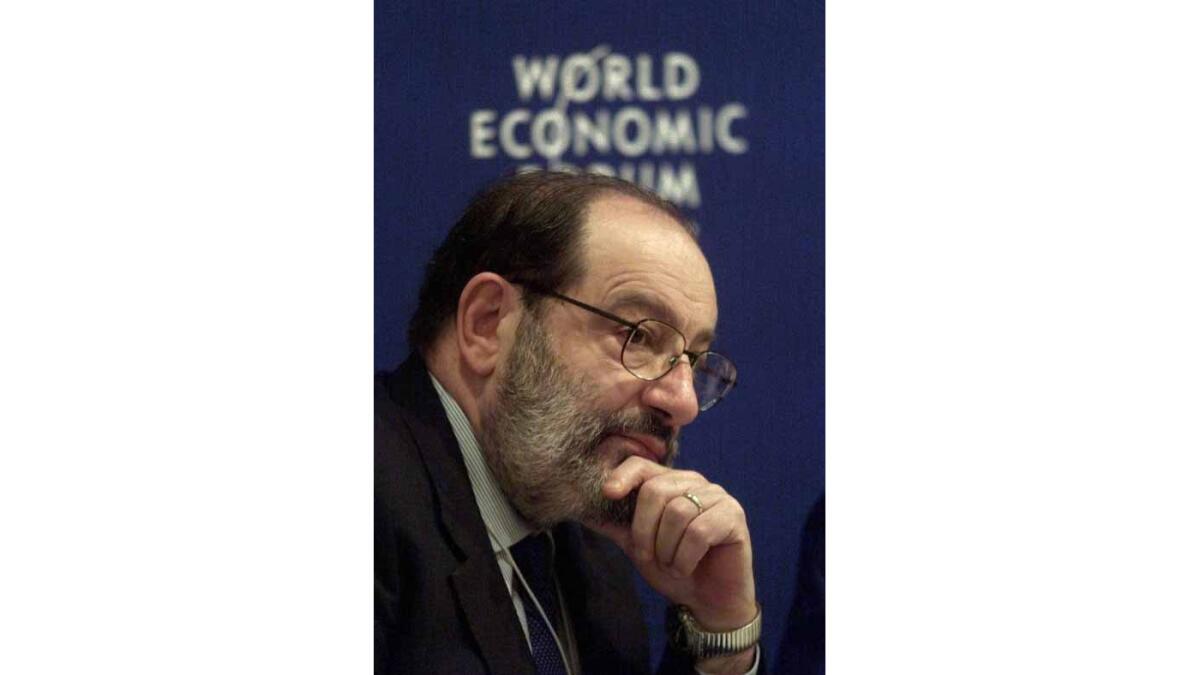

Italian author and philosopher Umberto Eco sits on a panel discussing the value of history and tradition during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Jan. 29, 2000.

- Share via

Reporting from New York — Literary giant Umberto Eco left behind a rich legacy of works, including “The Name of the Rose” and “Foucault’s Pendulum.” In 2005, he sat down with the Los Angeles Times to discuss his latest novel, “The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana.” This story originally appeared in The Times on June 13, 2005.

Umberto Eco settles into a couch in the second-floor den of Midtown Manhattan’s Morgans Hotel and pulls the stub of an unlit cigar from his mouth. After smoking for most of his adult life, he began cutting back about six months ago yet can’t quite leave the habit of touch behind. He’s not even sure he wants to leave smoking behind, having read somewhere that those with Alzheimer’s are disproportionately nonsmokers, suggesting nicotine as a guarantor of memory. And memory, Eco believes, defines the human soul.

Stop smoking, he jokes, and risk losing yourself.

“If there is something that we call soul, that’s memory -- it makes up your identity,” Eco, 73, says, his voice twisted by a thick Italian accent and interrupted by quick, explosive chortles. “All your befores, all your afters -- without memory you are an animal. You have no human soul. Even for a believer, you cannot go to hell without memory. Why to suffer so much if you don’t know why you suffer? It doesn’t make sense. If, in time, you lose your memory, there’s no meaning in paradise and no meaning in hell.”

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Memory lies at the heart of Eco’s new novel, “The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana,” which has brought him from his Milan home to New York for the start of a book tour that includes stops in L.A. this weekend.

In the novel, Eco explores the nature of a life separated from its context. Antiquarian book dealer Giambattista “Yambo” Bodoni suffers a stroke and awakens from the fog of a coma to discover he has lost the part of his memory that holds personal experiences. He has no idea who he is; his wife and two daughters are strangers, and the route from the hospital to his own house is a tourist’s adventurous trek.

He recalls quotations from books -- he initially tells his doctor he is Arthur Gordon Pym, an Edgar Allan Poe character -- but can’t discern which women he encounters are lovers from what his wife assures him was a licentious past.

Yambo’s wife, a psychologist, suggests he return to his childhood home, an estate in a rural village in northwest Italy, and use the archives of his youth to re-establish himself. So begins a reconstruction that cannot work because Yambo is now building a life from the outside rather than living it from the inside; it’s like the difference between observing life and experiencing it.

Still, memories revive and the strain of encountering a past he had repressed -- a youthful moral test during World War II -- bring him both to revelation and a renewed darkness that might or might not be death.

In the process, Eco slowly builds a fictional biography not of a character but of a generation, and illustrates it with youthful literary touchstones from the 1930s -- Flash Gordon and Ming the Merciless, Queen Loana and Mandrake the Magician, the Phantom and Mickey Mouse. Disney’s “Mickey Mouse Runs His Own Newspaper” slipped past the Italian Fascist censors, and Mickey’s pronouncements about the freedom of the press alerted the young Yambo (and Eco) that the written word had more potential than simple propaganda.

“The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana” is Eco’s fifth novel, and like the others it comprises both traditional narrative storytelling and inventive discourses on arcane subjects while drawing on philosophy, history and literature.

The approach was cast in Eco’s 1983 debut, “The Name of the Rose,” in which he used a murder mystery to explore the medieval Roman Catholic Church. The Middle Ages also gave rise to “Foucault’s Pendulum,” in which contemporary characters uncover centuries-old plots by the Knights Templar, and to “Baudolino,” about the days of Barbarossa, who fought the papacy in central Europe in the 12th century.

Eco advanced to the 1600s for the “The Island of the Day Before,” which imagined the race among navigators to establish longitude, and thus measure distance and time, which would give the discovering country an advantage in the battle to build colonial empires.

In the new novel, Eco stays in the relative present, reaching only back to the 1930s for his tale of a childhood lived in war. The research was more personal -- Eco spent World War II in a small village near Turin. “They were not dropping bombs, but the partisan war was going on so we got to avoid the bullets going around us, not from above,” Eco says.

Eco dipped into his own reassembled library of children’s books, antiquarian volumes and Fascist propaganda for the mementos included in the book.

“All during my adult life, every time I could in a flea market I re-set up my original library,” Eco says, adding that more recent Internet searches helped him fill the gaps. “Through the Internet, I succeeded in reconstructing my stamp collection of 1943. More or less I have found exactly the same stamps I had in my collection.... I have spent all my adult years continuously going back to my childhood

Other elements of the novel, he says, were borrowed from the lives of friends, including a crucial and harrowing story line about Yambo’s involvement in an encounter between German soldiers and Italian partisans.

“The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana” began with a flameout. Eco had contemplated writing an autobiography about growing up in Mussolini’s Italy but found five years ago that a friend had beaten him to the punch. “I said, ‘I hate you! You have stopped me, I can’t do the same,’ ” Eco says a few days after the hotel interview, speaking to a packed house at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y.

An encounter with another friend, though, jump-started the idea when the concept of memory came up in the conversation.

“I started to muse, that could be the start -- a man who loses his memory,” Eco says. “Not an autobiography but an objective biography of somebody else, and maybe of a generation.”

Eco viewed the project as the inverse of Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past,” in which memory propels the narrative. “The very fact that I couldn’t, like Proust, return to my personal memory” laid the groundwork. “That the character has to deal only with the objective memories makes his a reconstruction that is collective and generational.”

Eco’s physique has the soft roundness of a life well lived, his eyes sharp behind large-frame glasses. He is known primarily as a novelist and freely spices his conversation with literary references. But he is also a highly regarded and widely published expert on semiotics, the study of symbols and signs, which he teaches at Italy’s University of Bologna.

Sitting in the hotel den, with its genteel decor of leather and wood, Eco says he was surprised that the novel had even been translated after it first appeared in Italy last year.

“It speaks of Italy and a generation of memories,” Eco says, adding that he told his foreign publishers he “would not be offended” if they passed on the book. They didn’t. “The foreign publishers loved the book, and in the three countries in which it has been published -- Germany, France and Spain -- the reaction has been very, very positive.”

Eco hopes the universality of memory, and curiosity about other cultures, may give the book a boost in the U.S.

“Through the book, foreign readers discover the story of another country,” Eco says. “After all, we had never been to Macondo but when Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote ‘100 Years of Solitude,’ we learned something about Macondo.”

Yet the sense of nostalgia for lost childhood, lost innocence, may prove more significant.

Like Vladimir Nabokov, whose memoir “Speak, Memory,” begins with equating life as a candle flicker between two abysses of darkness, Eco writes in his new novel of life as a song. Without memory, the notes follow no path, each existing in its own moment, and the song is no longer a song. And without memory, each moment of life just a free-floating note.

“Literature, like philosophy, is always a meditation on death,” Eco says, still toying with the unlit cigar. “Otherwise, why to write?”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.