How a century-old traffic ordinance paved the way for L.A.’s deadly streets

- Share via

Good morning. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- The traffic ordinance that changed everything.

- Late evacuation orders in Altadena raise a haunting question: Could more lives have been spared?

- Stressed? Take the fast track to ‘womb-like’ euphoria at this new L.A. art experience.

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

L.A.’s deadly embrace of car-favoring traffic rules

For several years, I’ve been reporting on Los Angeles’s failure to deliver safer streets and curb traffic deaths. Despite on-paper goals to reduce the number of people killed while walking, biking and driving in the city, the death toll surged roughly 80% from 2015 to 2023.

You can probably guess how 2024 went, but here are some tragic early figures.

Preliminary data from the Los Angeles Police Department through Dec. 28 show 306 people died in crashes last year, including 170 pedestrians killed by motor vehicle drivers.

That’s a slight decline from 2023, when car crashes killed more people in L.A. than homicides did. But it marked the third straight year that more than 300 people died in crashes on city streets. More than 1,580 other crash victims were severely injured last year, virtually unchanged from 2023.

The full-year report has yet to be publicly released but is expected to be shared at a still-TBD news conference, according to LAPD’s data management division.

Why haven’t L.A. and other U.S. cities been able to stop the carnage?

We can chalk that up to a multitude of factors, including political will, driver accountability, public outreach and stronger safety regulations for automakers. But the simpler explanation is that we built our streets so drivers can go fast, which makes them more dangerous — especially for people walking.

It’s easy to normalize our car-centric world, since most of us living today were born after the automobile became a cultural necessity to get around. But the deadly street conditions we experience now were paved in large part by a century-old L.A. traffic ordinance that became the template for cities across the nation.

Today marks the 100th anniversary of that ordinance, so let’s time travel.

The origin story for L.A.’s deadly streets

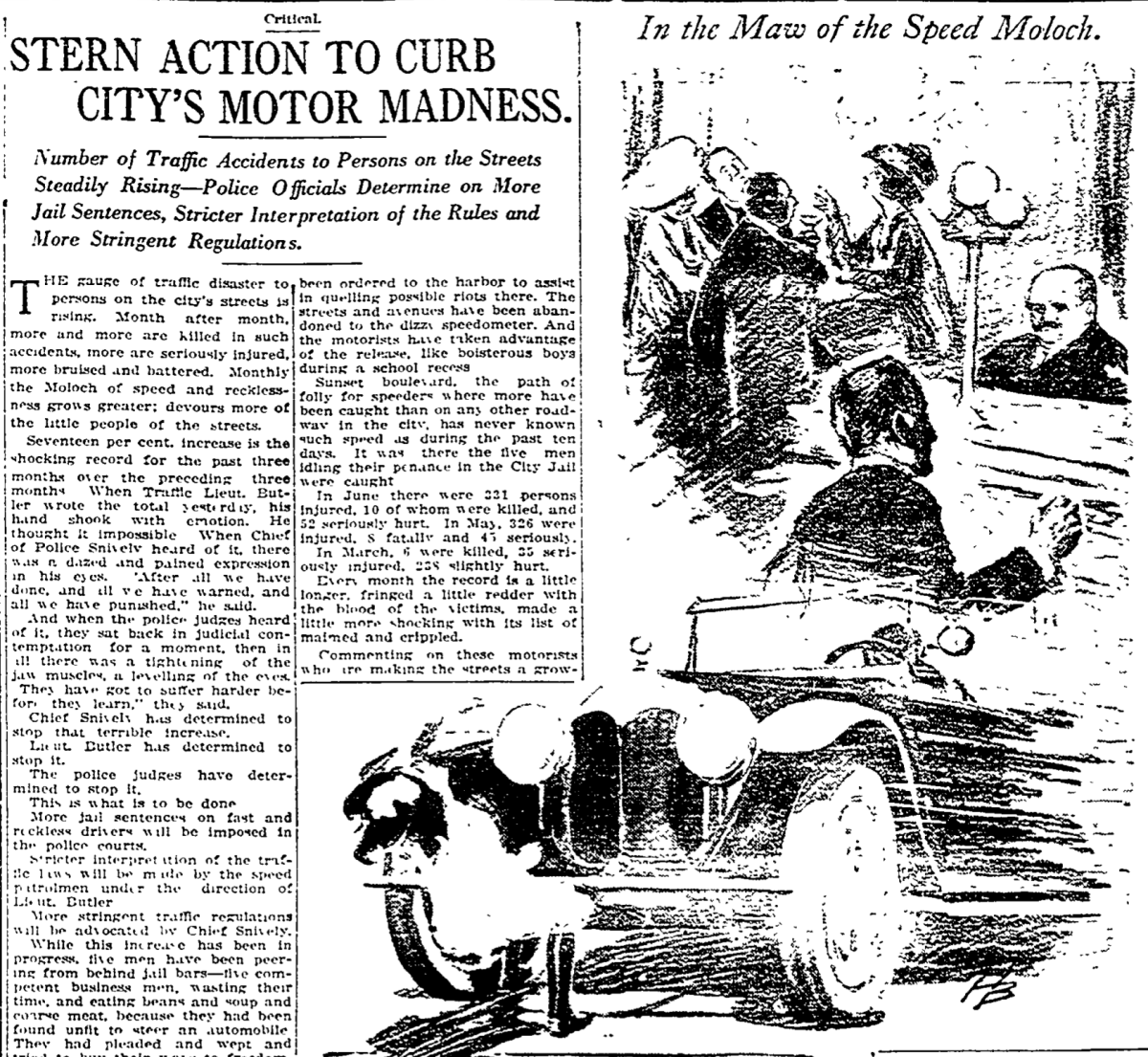

Los Angeles streets in the 1920s were a far cry from the car-clogged roads we have today. Most Angelenos walked, rode bikes (and horses) and took public transportation. For many, automobiles were viewed as lethal invaders. The numbers supported the perception.

In the early 20th century, drivers were killing thousands of people each year, many of them children. That was bad news for automakers and dealers trying to sell their machines in pedestrian-rich cities that villainized their products.

So one prominent L.A. Studebaker salesman, Paul G. Hoffman, crafted a plan: Create new traffic rules to reconfigure L.A. streets to be more car-friendly by giving drivers priority.

“What he wanted to do was find a way to make it easier to drive, to make it easier to drive faster, and also, importantly, to ensure that if a driver hit a pedestrian … the presumptive responsibility didn’t fall automatically on the driver,” tech historian Peter Norton explained.

Norton is a professor at the University of Virginia and chronicled Hoffman’s scheme in his 2008 book, “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.”

His body of research reveals the calculated effort by auto interests to shift the blame for traffic deaths from reckless drivers to pedestrians, clear the roads for cars and boost vehicle sales. A quick walk in your community will confirm who came out on top.

Lasting impacts

To make the car-favoring rules a reality, Hoffman recruited Miller McClintock, a Harvard PhD student who was studying motor vehicle traffic in cities. With financial support from the auto dealer, McClintock took on the role of traffic consultant and constructed the ordinance, Norton explained.

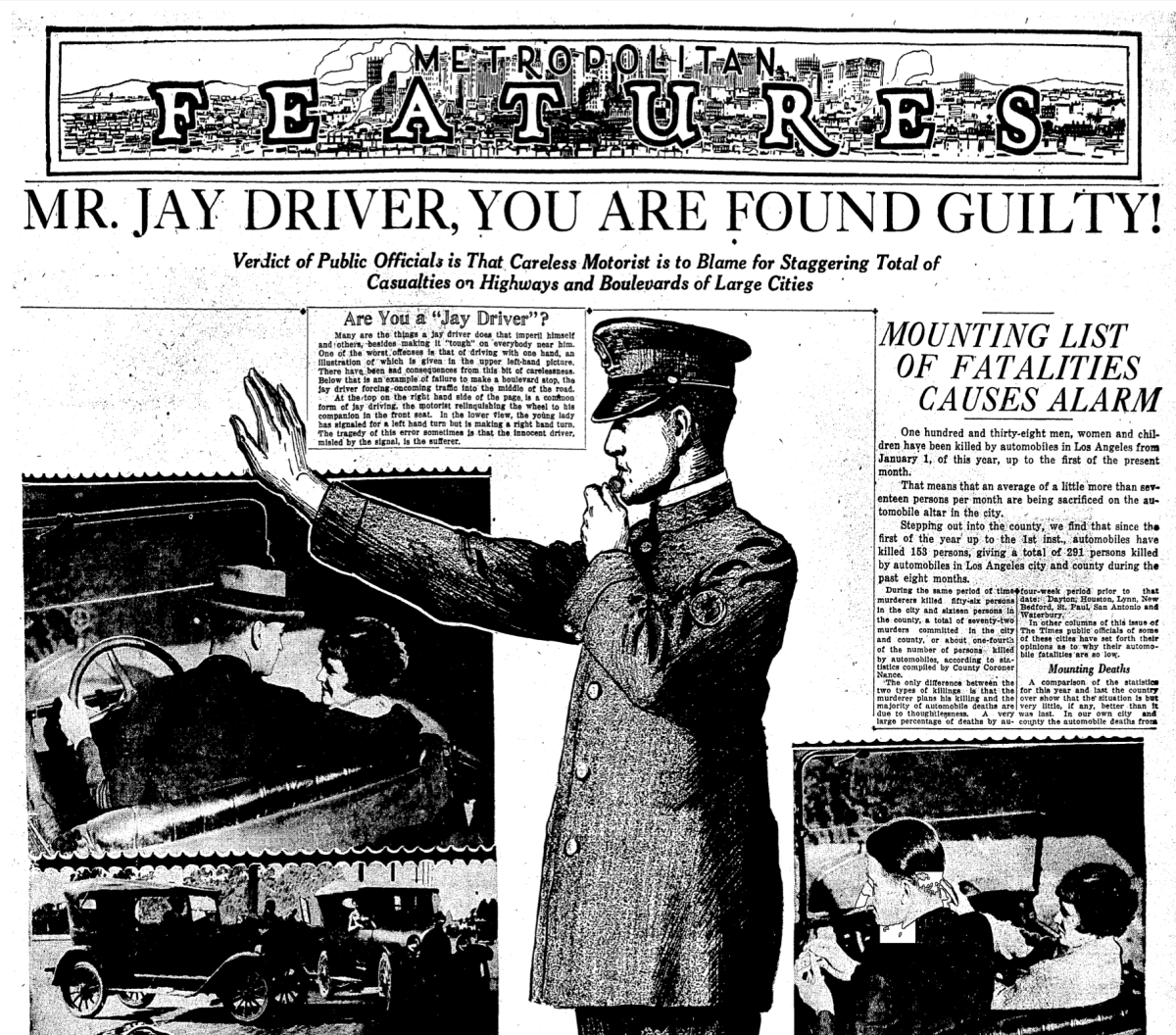

The most consequential provision, according to Norton, was that walking in the street outside of specific crossings was criminalized. That act was colloquially known as “jaywalking,” a term promoted by auto interests to shame people out of the streets that they’d had free access to for decades (“jay” is derogatory slang that essentially means a small-town idiot).

The ordinance also established that motorists were allowed to make right turns at red lights.

It was approved by the L.A. City Council in December 1924 but vetoed by Mayor George E. Cryer, a Republican, who took issue with the limitations placed on pedestrians and the safety hazards of allowing right-on-red.

“Pedestrians desiring to cross a street and who have been held up pending the release of traffic in the direction they desire to go are immediately menaced in the crossing by turning vehicles,” Cryer wrote in his veto message.

But the City Council — which Norton said was significantly influenced by auto industry interest groups — overrode his veto. The ordinance took effect on Jan. 24, 1925.

Basically, the people who stood to profit most from this technology successfully wrote the rules for how their often-lethal machines could be used in public space — and how anyone not using their products should behave as a result.

Remembering that sequence of events is important, Norton said, because it dispels the dominant narrative that car-centric streets were something a majority of Angelenos wanted.

“We forget that they didn’t dare try to get public support for the traffic ordinance of 1925,” Norton said. “The mayor was directly elected by the people of Los Angeles [and] vetoed that law. So it was not a democratic process, it was not a consumer demand process. It was a power struggle.”

Federal officials, also seeking to establish order on the nation’s increasingly deadly streets, took note of L.A.’s new rules.

“Rather than draft a traffic ordinance from scratch, [they] said: ‘Let’s take L.A.’s, we’ll tweak it a little bit, and it will be the official model municipal traffic ordinance of the whole country.’” Norton explained. “So wherever you are in the U.S.A. today, you’re living with a traffic ordinance that’s descended from that 1925 ordinance.”

Through lines to today

Norton noted that the ordinance was not the only factor that secured the automobile’s dominance of public space but was “symbolically and practically … the most significant” political and cultural shift in how we regulate roads and think about driver accountability.

But the new traffic laws didn’t instantly make streets safer. The Times reported in September 1925 that drivers killed more people in the roughly seven months after the ordinance took effect than in the same time period a year before.

L.A.’s transition to shift blame from fast drivers to pedestrians was eventually embraced on a national scale, Norton said. Pedestrians continue to bear the brunt of that normalization and battles for safer streets continue today.

California decriminalized “jaywalking” in 2022, with proponents noting that citations had been disproportionately written in communities of color. And last year, L.A. voters approved a ballot measure that requires the city to add long-planned safety upgrades for cyclists and pedestrians when it repaves streets.

For Norton, the history lesson reveals that shaking our “car-dominated status quo” is not a pipe dream.

“It’s possible to change things in ways that seem unimaginable,” he said, “and the proof of that is that L.A. did that in 1925.”

Today’s top stories

Multiple new blazes have erupted in Southern California

- The Hughes, Sepulveda and Laguna fires are the latest blazes in a nerve-racking week as Southern California heads into a fourth consecutive day of red flag fire weather warnings.

- The region is set for its first real rains of the winter, which would provide some welcome relief in this seemingly endless firefight.

- But fire weather could return if dry weather and Santa Ana winds return.

Late evacuation orders in Altadena raise a haunting question: Could more lives have been spared?

- Revelations about the timing of the evacuations have added more unease and anger in Altadena, where at least 17 lives and more than 9,000 structures — many of them homes — were lost in the fire.

- The Times reports that western Altadena got an evacuation order many hours after the Eaton fire exploded.

- Some community leaders have raised concerns about equity in the delayed warnings: Western Altadena has a more racially diverse makeup than neighborhoods to the east and is known for its rich Black history.

Empty office buildings in downtown L.A. could help housing crisis

- In the years since the pandemic, landlords downtown have watched in frustration as the value of their office buildings has plummeted.

- Landlord and developer Garrett Lee believes there’s a more reliable path forward than trying to convince tenants to return: converting offices into apartments.

- The idea took on new urgency this month as wildfires destroyed thousands of homes in Los Angeles’ Pacific Palisades neighborhood and Altadena, exacerbating the region’s long-running housing shortage.

How Trump’s executive actions could erase portions of California’s environmental agenda

- On the day President Trump took his oath of office, he promised to sign numerous executive orders that stand to undercut California’s aggressive auto emission standards, undo Biden-era environmental protections and boost U.S. fossil fuel production.

- Sticking to his promise, Trump is now seeking to put his stamp on California water policy by directing the federal government to send more water from Northern California to the Central Valley’s farms and Southern California cities. State officials say it could do harm.

The biggest snubs and surprises of the 2025 Oscar nominations

- “Emilia Pérez” led the field with 13 nominations, including for best picture, lead actress, supporting actress and directing.

- Karla Sofía Gascón, who stars in “Emilia Pérez” as the eponymous cartel boss who undergoes gender-affirming surgery, made history as the first out trans woman nominated in an acting category.

- Despite bringing the fun to “Gladiator II,” Denzel Washington did not earn an Oscar nod for the role. See other snubs and surprises here.

What else is going on

- Some price-gouging rules could be keeping high-end homes off L.A.’s rental market.

- Rents rise as refugees from the fires squeeze into L.A.’s tight housing market.

- Hundreds of tiny endangered fish were saved from the Palisades burn area — in the nick of time.

- The Palisades fire burned their high school. Now students face COVID-style, remote learning.

- Fires destroyed your family photos. Here are some ways to restore those memories.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Meet the architect of Trump’s attack on birthright citizenship: a California lawyer facing disbarment, columnist Michael Hiltzik writes.

- Invincible? After historic offseason, the Dodgers sure seem like it, writes columnist Bill Plaschke.

- Our biggest threat might not be earthquakes or fires, columnist Steve Lopez writes, but human nature.

- It’s now clear that America’s death penalty is dying one generation at a time, writes guest columnist Austin Sarat.

This morning’s must-reads

An ex-NBA player’s plan for a $5-billion Las Vegas arena is an empty pit. What went wrong? The project was former NBA player Jackie Lee Robinson’s lone source of income, he testified in a deposition. He used some of the funds to pay his mortgage and to purchase items from high-end stores including Gucci and Louis Vuitton. He also transferred thousands of dollars to himself, his wife and daughter.

Other must-reads

- Under Trump, we could be flying blind when it comes to bird flu and other infectious diseases.

- Housing tracker: Before the fires, the Southern California housing market downshifted.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to [email protected].

For your downtime

Going out

- 😌Stressed? Take the fast track to ‘womb-like’ euphoria at this new L.A. art experience.

Staying in

- 📖The making of ‘La Bamba’ was a family affair. An upcoming book with never-before-seen photos will show how.

- 🍴 Here’s a recipe for penne with caramelized cauliflower, garlic and chile.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

A question for you: What movie do you think should win the Oscar for Best Picture?

Oscar nominations landed Thursday morning after being delayed twice by the Los Angeles wildfires. As expected, “Emilia Pérez” led the field with 13 nods, including best lead actress for Karla Sofía Gascón, who made history as the first out trans woman nominated in an acting category.

What movie do you think should win best picture?

Email us at [email protected], and your response might appear in the newsletter this week.

And finally ... your photo of the day

Today’s great photo is from Times photographer Wally Skalij at the scene of the Hughes fire, which ignited Wednesday morning north of Castaic.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Defne Karabatur, fellow

Andrew Campa, Sunday reporter

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Hunter Clauss, multiplatform editor

Christian Orozco, assistant editor

Stephanie Chavez, deputy metro editor

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.