- Share via

FRENCH CAMP, Calif. — As coronavirus cases began to grow in San Joaquin County in June, Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs proposed requiring citizens to wear a mask in his city in the center of the fertile valley, where agriculture is king and poverty pervasive.

The response he received from the county emergency services director, a key figure in coordinating the pandemic response, was disquieting, he said.

“Stay in your lane,” wrote Shellie Lima in a June 9 email to Tubbs obtained by The Times, days before the county allowed card rooms, hotels and day camps to open. “I am against the proposed mask ordinance for Stockton ... Why would our elected officials feel that they have the medical understanding to do so?”

Weeks later, San Joaquin is so overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases that military medical teams have been sent to two local hospitals. ICU beds are scarce, and the surge has hit farm workers especially hard.

Though county figures say about 31% of overall cases are in the Latino community, some on the front lines estimate that up to 70% of cases from the recent hike have hit in that demographic, in a region where they account for about 42% of the population, according to census figures. Experts agree that official case counts across the state may be low because of testing problems.

“Maybe they don’t think it’s serious, maybe the people who are most likely impacted are not a priority for them, or maybe it’s just a lack of understanding of the science,” said Tubbs of the county response. “We keep treating it like this wasn’t avoidable. It was.”

In a recent interview with The Times, Lima said that sending the email from her county account was an accident, and its contents did not reflect the views of her office. But she added that “so much has changed” since she wrote it, and acknowledges the county response “could be better.”

As Gov. Gavin Newsom detailed Friday, there are many reasons Latino workers, including farmworkers who make up 93% of the state’s agricultural laborers, are bearing the brunt of California’s cases. Farmworkers in particular often live in crowded housing, sharing space with other families. Many are transported to job sites in packed vans, and they have little access to healthcare, including testing, and personal protective equipment. When they fall ill, the realities of lost wages may drive them to work anyway, exposing others.

But according to advocates for agricultural employees, the coronavirus is also ravaging Latino farmworkers because they have long been treated as disposable labor in California, risking their lives in heat waves and pesticide-laden fields to help put food on people’s tables. The pandemic has only amplified the brew of conservative politics, economic pressures and historic disparities that run through the farmlands of California’s inland counties, they say, resulting in government aid that seems too little, too late.

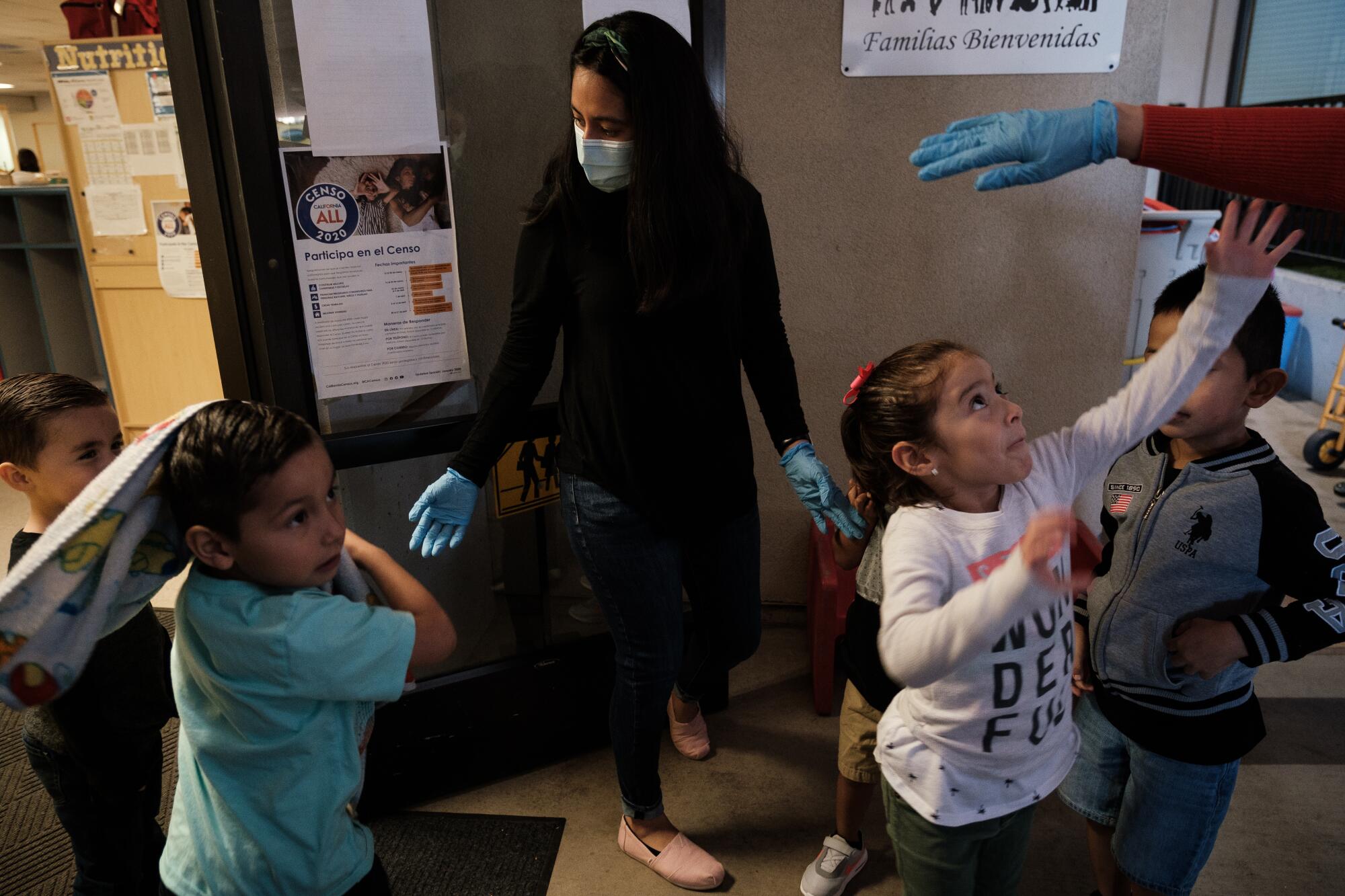

“It’s just alarming,” said Jose Rodriguez, president of El Concilio, an advocacy and services organization that runs child-care centers and affordable housing for farmworkers. “It’s just disappointing how there is not a sense of urgency by public health or healthcare providers to find out how these folks are getting it and then try to contain it.”

Though the virus has struck other farm counties, such as Monterey, San Joaquin stands out as a place that dodged the pandemic early but did not use that time to prepare. As of Friday, the county surpassed 10,000 cases and has counted 110 deaths. More than 3,700 of its cases have come in the last two weeks.

California’s 420,000 farmworkers are working through the crisis. But language barriers and a lack of communication on the coronavirus put many at risk.

San Joaquin’s public health officer, Dr. Maggie Park, said her county has been working to protect farm laborers since March, when the cherry-picking season started and migrant workers began to arrive, but “despite everyone’s best efforts, we still have some outbreaks. ... Sometimes you just can’t control that.”

Farmworkers and their families in San Joaquin say they have seen little help so far.

Citlali Mendoza, 18, currently lives with her farmworker parents in a low-slung complex of cramped apartments near the county jail. Each year, the family spends about nine months in San Joaquin before returning to Mexico for the remaining months.

Mendoza, who is starting at Modesto Junior College this fall, said she is “very worried” about her mother’s and father’s heath, especially because of the tight conditions of their apartment complex. Her unit is a few hundred square feet, filled with framed prints of Catholic saints and a Last Supper wall clock, and shared by six people. But she says the family has received no aid or information from government sources about the spread of the virus.

“It’s hard,” she said. “I’m really scared.”

Eulogio Granados is a middleman who hires farmworkers and contracts the crews with local farms — a common arrangement that some argue shields growers from the legal responsibilities of being direct employers, but which growers say is necessary because their labor needs fluctuate with the season. Granados said that he has paid out of pocket for masks for his crew, costing him $300 for the last batch of 100 masks. His cousin has been sewing cloth ones for him to pass out.

“I should get help, but nobody is doing it,” Granados said, standing near a field of green tomatoes where his crew was clearing weeds. “That’s a lot of money.”

Gloria Lopez, another labor broker, said her employer requires social distancing and had received thousands of masks from the county this week. She was planning on distributing them as soon as she received them. But nearby, Luis Diaz, 19, said his employer, different from Lopez’s, didn’t provide protective equipment, and he believes there should be “more help for the community.”

Tim Pelican, the county agricultural commissioner charged with helping about 3,580 farms covering 787,000 acres, said he too is frustrated by the slow pace of response. He said that while the county is working on programs, including mobile testing for farmworkers and quarantine sites for those who live in crowded conditions, they are not currently available.

“From my standpoint, I think some of the actions came along a little too late,” Pelican said. “I think everybody knew it was going to come, it was just when.”

Newsom announced Friday that his administration was working on a program for quarantine housing for farmworkers, and Park said she discussed it on a call with state officials Thursday for the first time. Newsom also promised more education for employers, increased access to sick leave and enforcement of labor laws, including requiring employers to report outbreaks.

Rodriguez, the community advocate, said testing and tracking for the Latino community is another problem. Many residents are undocumented, lack insurance and are fearful that seeking treatment could lead to deportation, he said. His organization recently arranged with the county department of public health for a pop-up testing site for the Latino community. He said 300 people turned out, but the public health department arrived with only 30 tests.

Rodriguez arranged for another day of testing at a Latino grocery story. More than 600 showed up, though only 300 tests were available. Rodriguez said that about 10% of the tests came back positive, but he was again dismayed that the public health department did not follow up. The lab sent results directly to his organization to share with the test takers, he said.

Park said the county continues to do contract tracing, but is overwhelmed by the numbers. On one recent day, the county had about 450 positive cases reported, she said. Each of those cases has probably exposed multiple people.

“It almost becomes an impossible feat to get to all of them,” Park said. She added that many farmworkers report that they are unemployed, fearful of creating trouble with employers, making it impossible to pinpoint outbreaks.

San Joaquin’s supervising epidemiologist, Kelly Rose, said the state system for tracking also makes it difficult to determine how many farmworkers have fallen ill because it may miss some involved in agricultural work. Truck drivers, she said as an example, may be working on farms but could be classified as transportation workers. San Joaquin has officially counted only 102 coronavirus cases attributed to farmworkers, according to Rose’s data.

County and state officials said they are working hard to ensure that San Joaquin and similar counties have the materials and manpower needed to handle rising cases. Brian Ferguson, spokesman for the governor’s office of emergency services, said the state has sent more than 600,000 N95 masks to the county, along with more than 1.5 million surgical masks and other supplies. Statewide, Feguson said that nearly 12 million surgical masks have been allotted specifically for agricultural workers.

Lima said San Joaquin has released information in Spanish and other languages. The county has also passed out 1,200 sanitation kits to essential workers, and Pelican, the agricultural commissioner, said his agency distributed 2,000 cloth masks to migrant housing facilities, along with about 500,000 respirator masks, directly to growers and employers.

Juanita Ontiveros, who began working for farmworkers’ rights with Cesar Chavez decades ago, said she is not surprised that help has been slow to arrive. She points out that farmworkers have long had to fight battles for “basic human rights” such as shade and clean water. Recently, she delivered rubber bands to field workers who were trying to make masks out of leftover irrigation fabric, she said, and has been doing field inspections to help laborers understand their rights for social distancing and other protective measures.

Ontiveros said state and county governments need to think ahead when it comes to protecting California’s rural Latinos. Tomatoes are starting to ripen, she said — requiring workers to ride on large harvesters while the fruit is pulled down belts for sorting. She would like to see Plexiglass shields between workers, similar to what has been placed in restaurants and grocery stores.

And she is concerned about the closures of migrant camps in the winter. Some farm laborers return to their home countries, while others try to scrape by in temporary living situations. Ontiveros said the state and counties should keep the housing available to the essential workers, arguing it is dangerous to force them to travel during the pandemic.

She said that kind of planning requires the “nitty gritty” insights of those affected, but farmworkers themselves have been largely excluded from conversations about their needs.

“A lot of times [government thinks] because they are farmworkers, [government] can say what’s good for them, but hardly ever ask them for their own suggestions and ideas,” Ontiveros said.

Some in Stockton said the county has also been too slow helping the homeless population, largely people of color, which presented a growing crisis in the area before the pandemic. Though a state program to move some vulnerable unsheltered people into hotels helped, providing 76 rooms for those at risk of contracting the virus, 71 homeless people have caught it, according to official county figures, sending them to local hospitals in some cases. Park said the county is now working to secure hotel rooms for homeless people waiting for test results.

But homeless advocates said there is no place for unsheltered people to go if they are positive but don’t need hospitalization, or are recovered enough to be released. One of the city’s main homeless service providers, the Gospel Center Rescue Mission, “jumped into the fight,” said its chief operations officer, Britton Kimball. Kimball personally helped refurbish two buildings in about a week to serve as recovery centers for COVID-positive homeless people, the only such beds in the county, he said.

So far, about 50 people have used the facility. Kimball said that without it, homeless people with the virus could be forced to remain on the streets, potentially spreading the virus.

“You could think that from the county’s perspective this would trump everything, but that does not seem to be the case,” Kimball said recently, as some of his virus-positive clientele sat in a private yard taking in sunshine. “Promises were made. They have been slow in fulfilling them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.