- Share via

Los Angeles, six years ago: A young woman boarded a bus to meet her boyfriend for the first time.

They had been dating for nearly two years, but she had only ever spoken to him over the phone.

Her destination was San Quentin. In his cell on death row, her boyfriend kept a cellphone. The phone is how they met, how they fell in love.

Alone and in a new country, she was introduced to this man, a gangster and a murderer, with the promise that he would help her survive. She fell for the sound of his voice on the end of the line, this voice that gave her all she needed: money for her bills, support for her children, the patience and devotion of a man who has nothing but time and no one to lavish it on but her.

This is a love story, but it is also a story of how the Mexican Mafia does business. Exploiting the state’s failure to control the use of cellphones behind bars, members of the prison-based syndicate collect money and order murders on city streets many miles from the prisons where they are caged.

About two-thirds of the Mexican Mafia’s 140 members are held in California prisons, which are inundated with illegal cellphones. They use the phones to traffic in drugs, collect money and order murders.

The woman’s account shows how these men use lovers and friends — some willing participants, others unwitting ones — to do what they physically cannot. At the direction of her boyfriend, who played a supporting role in the Mexican Mafia, she distributed his money and arranged conference calls with other inmates. She knew it was wrong, she said: “But I didn’t know how far the consequences would go.”

They would lead to murder; to a new home in a new city where, she hoped, no one from the Mexican Mafia would find her; to a courtroom in Compton, where, after taking the witness stand, she was shown a photograph of a dingy apartment bathed in the weak light of a street lamp. Rain had fallen that night, darkening pavement already blighted by blood.

She began to shake, then said: “I remember everything.”

Brenda is from Tijuana. Her story starts with Nicholas Solorzano Martinez, a member of a Compton gang called Tortilla Flats who is nicknamed Funny. After doing time in California prisons, Solorzano was deported to Mexico, where he met Brenda. The two had a daughter together.

After finishing his shift one night as a security guard at a Tijuana nightclub, Solorzano and two other bouncers went to a bar called the Black Bull, where they shot a man to death in a drunken brawl, according to Mexican media reports.

Brenda asked where he lived. ‘If I tell you,’ she recalled Beto saying, ‘you won’t want to talk to me.’

Solorzano shared a prison cell with another deportee called Flaco. Flaco was from Hollywood and had a cellphone, Brenda said. He told Brenda he would introduce her to someone who could help her “survive” in the United States, where she had crossed the border without a visa or job prospects.

Flaco patched in a man called Beto. Brenda asked where he lived. “If I tell you,” she recalled Beto saying, “you won’t want to talk to me.”

He lived on “paseo de la muerte,” he said. Death row.

Alberto Martinez had been sentenced to death in 2010. A woman hired Martinez and several of his friends in the Pacoima Flats gang to murder her brother, who was due to inherit the family’s trucking business. Martinez drove the car used to abduct and kill the man.

Martinez didn’t tell Brenda any of this, but she knew he must have done something terrible to be on death row.

In the courtroom, a defense attorney asked: Didn’t that give you pause?

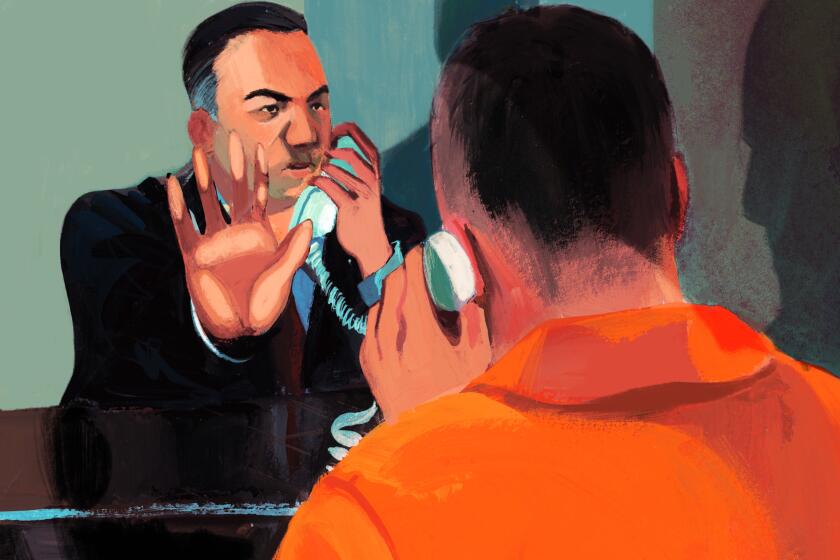

Federal prosecutors say Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, a criminal defense attorney who once taught English, connected the Mexican Mafia’s bases of power in prisons, jails and the streets of Southern California.

“It’s not that it didn’t bother me,” she replied. “It’s that I didn’t ask if he did it or not. They all say they didn’t do it.”

Picking at a plate of chilaquiles at the Lucky Star Cafe after testifying, Brenda told a Times reporter she found Martinez “extremely intelligent and well-spoken. He’ll say anything a woman wants to hear.”

Soon, they talked every day. Martinez got a higher-quality phone that allowed them to video-chat. Seeing him, she thought he had “the face of a bad person.” The attraction only deepened.

Martinez got her a small bungalow apartment on 133rd Street in Compton and paid the $700 monthly rent. He sent her money: for her phone bill, to get her nails done, to shop at the mall. He bought clothes and school supplies for her daughters and sent them text messages wishing the little girl a good day at school.

Then, Martinez asked Brenda to send some money to his friends’ wives. She knew his friends were inmates, but she did not think much of it.

Men began dropping off cash at Brenda’s apartment, $1,000 to $2,000 at a time. Martinez gave her the names and addresses of the “señoras” and she sent them money orders.

Brenda did not believe the money was derived from crime, she testified. Martinez told her members of his gang with legitimate jobs were “helping the ones inside,” she said.

One day Martinez wanted Brenda to send money and “thank-you cards” to some people, she recalled. He told her to write down some names and post office box numbers.

Seeing him, she thought he had ‘the face of a bad person.’ The attraction only deepened.

A prosecutor displayed the list in court: Fernando Bermudez, Raul Garcia, Carlos Molina, Hector Ayala, Jesse Gonzalez.

The five men are members of the Mexican Mafia, Deputy Devon Self of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department testified. Ayala and Gonzalez are on death row. Garcia and Molina run Martinez’s old neighborhood in Pacoima.

Martinez told Brenda that women “aren’t supposed to know about the business,” she recalled, but he confided in her that he works for what he called “los chingones” — the bad-asses. He told her she must always speak of such men with respect. Not once did he use the words “Mexican Mafia,” she said.

Testifying in the defense of a Mexican Mafia member in 2019, Martinez described himself as an associate of the organization, not a full-fledged member, and acknowledged using cellphones in prison.

Self estimated that hundreds of state prisoners are illegally using cellphones behind bars. Some are smuggled in by guards and staff, while others are brought in using drones that drop the phones onto prison yards. “I believe at the L.A. County jail we even shot one down,” the deputy testified.

A California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation department spokeswoman, Terry Thornton, said in a written statement that investigators use cell inspections, clothed and unclothed body searches, metal detectors, X-ray scanners, dogs and audio and video surveillance to try to root out contraband cellphones.

Thornton said Martinez has been caught four times with cellphones between 2016 and 2019. She would not provide specifics of the incidents or describe what punishment Martinez received, saying such information is protected under state law.

Martinez didn’t respond to a letter seeking comment.

Martinez, Brenda testified, was the first to say, “I love you.” But she admitted falling for a man whose embrace she had never known.

She knew what other inmates called Martinez — Crook — but she preferred Beto (short for Alberto) and Chino (for the curly hair that tumbled down his back).

Almost two years after they had met, Brenda boarded a Greyhound bus with her daughters and brother. He would watch the girls at a motel while she went to San Quentin to see Martinez in person for the first time.

She didn’t tell her brother where she was going. “He knew the types of boyfriends that I had,” she testified, adding: “The less he knew, the better.”

San Quentin is the state’s oldest prison, built in 1852 on a scenic bluff overlooking the San Francisco Bay. Inside, Brenda felt she had entered “a sanitarium, a crazy person’s house.” Granted a contact visit, she was locked with Martinez in a wire enclosure that she likened to a “birdcage.”

A guard snapped a photograph of the two embracing: Martinez stares into the camera, a faint smile playing on his lips. Brenda clings to his arm. The crown of her head just reached his chin.

‘It’s that I didn’t ask if he did it or not. They all say they didn’t do it.’

On the long ride home, Brenda thought about how much the prison had frightened her. Back in L.A., she told Martinez that she didn’t want to go through life with a voice on the phone. That she didn’t see a future with him.

Martinez responded by calling even more, sometimes 20 times a day, she said. When she didn’t pick up, people showed up at her home. They acted friendly but tried to come inside.

When she answered Martinez’s calls, he cursed: “Where the f— you been?”

Brenda was leaving a market on Willowbrook Avenue, pushing her daughters in a stroller, when a young man with long hair asked whether she needed help with her bags. She and Guillermo “Willy” Toledo ended up exchanging phone numbers.

Toledo came to Brenda’s apartment later that day. As they talked, a man from Toledo’s gang, Compton Varrio Largo 36, showed up and asked to speak with him outside.

When Toledo returned, he asked Brenda whether she was seeing someone. She admitted she had been dating an inmate on death row called Beto.

Toledo said Beto sent the man from his gang to talk to him. Brenda was certain now that Martinez had people watching her.

On the long ride home, Brenda thought about how much the prison had frightened her. Back in L.A., she told Martinez she didn’t want to go through life with a voice on the phone.

As Brenda and Toledo grew closer, she told him “a little about what I was doing” — the cash, the money orders, the phone calls. Toledo, she said, warned her “something serious” could happen if the money ever came up short.

The next time some men came to her apartment with cash, she refused to take it. “I said, ‘I have things to do. I’m not going to do favors anymore.’ ”

Martinez, she said, learned of her relationship with Toledo, whom he dismissed as “a nobody from the neighborhood.”

Toledo had done time in prison for robbery and carrying guns, court records show, but he wasn’t connected like Martinez. He lived with his mother, scraping out a living painting houses and collecting government assistance, Brenda said.

One day Martinez called her and asked, “Where’s Willy?”

Brenda lied: He’s at his mother’s.

“No, he’s not,” Martinez replied. “His car’s parked in front of your house.”

One night, a seven-piece band started setting up outside Brenda’s apartment. There was a drum kit, a tuba, a trombone and a guitar. One man had strapped a large drum to his chest. Another held a pair of cymbals.

They brought a bouquet of flowers and balloons that read “Hugs and Kisses” and “Happy Anniversary.”

Martinez had sent the band to Brenda’s home to mark the two-year anniversary of their first phone call.

Several friends of Martinez were there, including a woman who was holding a phone, Brenda recalled. Martinez was on FaceTime. She had never seen him so in love, the woman remarked.

Toledo, she said, warned her ‘something serious’ could happen if the money ever came up short.

She held the phone close to the microphone so Martinez could dedicate song after song to Brenda.

Wearing a hot-pink dress and clutching a drink, Brenda sang along to ballads by Ariel Camacho and Banda MS, according to a video shown in court. Toledo was there too. She didn’t dare to dance with him with Martinez watching from hundreds of miles away.

The loud music drew the cops, who warned the crowd. When the deputies returned shortly before midnight, Brenda, the band and Martinez’s friends walked several blocks to Toledo’s home, where the party continued until 3 a.m.

Martinez was on FaceTime for all of it — for so long that the phone died and had to be charged up again.

A deputy led a sullen-faced man into the Compton courtroom. He was wearing an orange jumpsuit, his wrists shackled to his waist.

The prosecutor asked Michael Haynie how he felt about being on the witness stand. “I feel nervous, um, overwhelmed,” he said. “I feel ashamed.”

Haynie had pleaded no contest to murder and assault and was testifying in exchange for a reduced sentence of eight years.

A member of an East Los Angeles gang called Stoners-13, Haynie was in prison for operating a chop shop when another inmate connected him via cellphone to Martinez.

When he got out, Haynie said he started doing “favors” for Martinez: “Pick up money, try to get ahold of somebody for him.”

One day, Martinez called Haynie and said he was having trouble reaching Brenda. Martinez wanted Haynie to get her new boyfriend on the phone and “put hands on him, to beat him up,” Haynie testified.

‘Get out of here,’ she recalled him saying. ‘Move, or I’ll shoot you.’

Martinez sent him a photograph of the man, Haynie testified. He told him to find a Pacoima Flats gang member, Francisco Virgen, who knew where Brenda lived.

Haynie’s brother-in-law, Victor Soto, drove them to a Jack in the Box in Pacoima, where Virgen was waiting on a motorcycle. As Virgen got in the car, he showed Haynie a gun, Haynie testified.

Brenda and Toledo were inside her apartment when they heard a knock at the door.

Haynie and Virgen told Toledo that Martinez wanted to speak with him. There’s nothing to talk about, Toledo said angrily. Haynie, trying to “cool him down,” made small talk with Toledo. Brenda brought out some beers, which they drank on the steps. Soto, who had been waiting in the car, came out to see what was taking so long.

Toledo got a phone call and walked across the street, where a black car had pulled up. When he returned, Haynie testified, his hand was in his pocket. Toledo walked inside the apartment, and from where they were standing by the doorstep, “you hear him put one in the chamber, like real loud,” Haynie said. “He wanted us to hear it, that he had one.”

When Toledo came out, he agreed to talk to Martinez. Haynie estimated the two spoke on the phone for no more than five minutes. “You could tell the conversation wasn’t going good.”

Toledo hung up and told Brenda: “Let the men talk.”

Brenda remembered it somewhat differently: Toledo was talking to the men in English. She did not understand what they were saying, but it seemed friendly. Then Toledo turned to look at her, “but not like usual. He just said, ‘Go in the house. I’m going to talk to them.’ ”

A few seconds after the door closed behind her, she heard a thud, as if something — or someone — had been thrown against the wall. She ran outside and saw Haynie holding Toledo from behind while Virgen and Soto pummeled him in the stomach.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Brenda threw herself in the middle of it. “I was trying to throw punches and kicks, everything I could.” Virgen drew a gun, she said. She grabbed the barrel, but he didn’t let go. “Get out of here,” she recalled him saying. “Move, or I’ll shoot you.”

Virgen shot Toledo in the leg, Haynie said. “I panicked. People were looking out their windows. A lady had come out.”

Virgen handed the gun to Soto, who pointed it at Toledo’s head, Brenda testified. Virgen nodded once and Soto pulled the trigger, she said. She crumpled to the ground with Toledo, trying to stanch the blood that was streaming from the hole in his head.

Virgen and Haynie ran, she said, but Soto backed away slowly. “Let’s go,” she heard the others yell.

No gun was found on Toledo’s body, authorities said.

The jury convicted Virgen of second-degree murder but could not reach a verdict as to Soto, who, rather than going to trial again, pleaded no contest to manslaughter.

Martinez was not charged with Toledo’s murder. Ray Lugo, the sheriff’s detective who investigated the case, said local prosecutors would not bring a new case against an inmate on death row, where they are already serving the most severe punishment under the law.

“What are you going to give them, double life?” he asked.

Lugo said he wants to see Martinez charged by federal authorities in a racketeering case that would send him to a federal prison, “where they have a little more control over the inmates and phone access is not an issue.”

The detective believes the corrections department should use signal-jamming technology to cut off cellphone service on death row.

Speaking with detectives through the bars of a holding cell, Martinez admitted being in love with Brenda but denied having anything to do with Toledo’s death.

“People are dying and they’re getting away with murder,” he said. “These guys on death row think nothing can happen to them.”

Lugo said he traveled to San Quentin to interview Martinez, who refused to come out of his cell. As a ruse, the detective asked the guards to tell him that Brenda had been seriously hurt.

“We just winged it,” Lugo said. “I wasn’t going to make a 500-mile trip for nothing.”

Speaking with Lugo and his partner, Rich Ruiz, through the bars of a holding cell, Martinez admitted being in love with Brenda, Lugo said, but denied having anything to do with Toledo’s death. “He said, ‘I have no idea who could have done this.’ ”

Before they left, Lugo told Martinez that Brenda might not make it and asked whether there was anything he wanted to say to her. According to the detective, Martinez said: “Could you tell her that I still love her very much?”

Back at the Lucky Star Cafe, Brenda shared a memory of her last conversation with Martinez. Three years after Toledo was killed, she said, he called her and asked where she was living. She refused to say.

Then the voice she once thought could give her all she wanted, that made her fall in love over a phone line, asked her not to testify.

“I love you,” Martinez said. “I’ll never do anything to you. But others will.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.