A slimmed-down LAPD seems here to stay. What happens to crime with fewer cops?

- Share via

- New projections show that between recruiting shortfalls and attrition, LAPD leaders expect to lose more than 150 officers in the coming fiscal year, leaving a force of about 8,620, which would be the lowest staffing level since 1995.

- LAPD officials have long argued that 10,000 officers are needed to ensure public safety, but recent crime statistics indicate the city is becoming safer even as the department shrinks.

When Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass gave pay raises to the city’s rank-and-file police officers last year, she sold it as a sensible investment toward regrowing the LAPD to the 9,500-member force it was before her election in 2022.

In the months since, Bass and leaders in the Los Angeles Police Department have continued to project optimism about reaching that goal.

Behind the scenes, though, officials are starting to confront the reality that the LAPD buildup won’t happen anytime soon — while acknowledging that the country’s third-largest police department may even continue to shrink.

New projections included in the department’s fiscal year 2026 budget proposal show that between recruiting shortfalls and attrition, leaders expect to lose more than 150 cops, leaving a force of about 8,620 by June 30, 2026. That would mark the lowest deployment in roughly 30 years, records show.

During public appearances, Bass, LAPD Chief Jim McDonnell and other top leaders are still making the case that the department needs to grow, arguing more manpower is required to maintain public safety. The Palisades fire recently showed the department can be stretched thin during a major disaster. Meanwhile, the upcoming World Cup and Olympic Games loom as massive security challenges.

Coverage of the firefighters’ battle to improve containment over the Eaton and Palisades fires, including stories about the latest death count and victim frustration.

Yet even as the LAPD has gotten smaller, by some measures the city is becoming safer — despite public perception to the contrary. Police Department data show that many types of violent crime are down, especially homicides and shootings, continuing a years-long decline after increasing during the pandemic.

LAPD leaders have long debated how many officers are necessary to patrol the city’s sprawling territory, stretching from Wilmington to the San Fernando Valley. Although the push has historically been for more manpower, the latest crime trends have left some wondering whether the recent declines in staffing have actually led to a right-sizing of the department.

Some officials say having fewer officers available for patrol duty and other functions will make it difficult to sustain the recent declines in crime. Not only will people experience even longer wait times when they call 911, some crimes also will inevitably go unsolved for a lack of available investigators — both of which erode public trust, they argue.

L.A. is hardly alone in its struggles with hiring and retaining officers. Like other big-city agencies, the LAPD is facing tougher competition for top candidates from other suburban law enforcement agencies, as well as the private sector.

The department has in recent years started offering signing bonuses to entice applicants, as well as extra incentives for current officers who rent or buy a home in the city. It has also beefed up its marketing budget, advertising on TikTok and other social media platforms in order to reach younger candidates — who tend to share a less favorable view of law enforcement than their elders.

Officials have also explored rehiring recently retired officers, and bringing on more civilians to take over desk jobs currently being performed by sworn officers. Polling from recent years suggests that most Angelenos have little interest in shrinking the department.

The latest police contract ratified in the fall of 2023 boosts the starting pay of officers by nearly 13%, with guaranteed 3% annual raises over four years. LAPD starting salaries now top $86,000 — higher than those in Pasadena, Long Beach and Burbank, but still lower than Beverly Hills and Santa Monica.

The City Council signed off on the raises, over objections from activists and some city officials, who say that they would not significantly boost recruitment and come at the expense of other basic services such as park maintenance and street paving.

For the record:

8:08 a.m. Jan. 24, 2025An earlier version of this story misspelled the last name of L.A. City Councilmember Nithya Raman as Rahman.

Among those raising concerns were Councilmember Nithya Raman, who said she voted against the LAPD raises because she wasn’t convinced they would fix the real problem: People are simply not going into law enforcement in the same numbers as before, for reasons other than the pay.

“We are not really grappling with the fact that spending a lot more money on LAPD has not yielded more results or increases in staffing,” she said.

The fixation on hiring more cops now is distracting from the development and long-term investment in community-led programs that research has shown are more effective in addressing the underlying causes of crime, Raman said.

“We need a holistic alternative response,” said Raman, who is part of a new ad hoc council committee on boosting alternatives to police. “Even that conversation has not been had yet.”

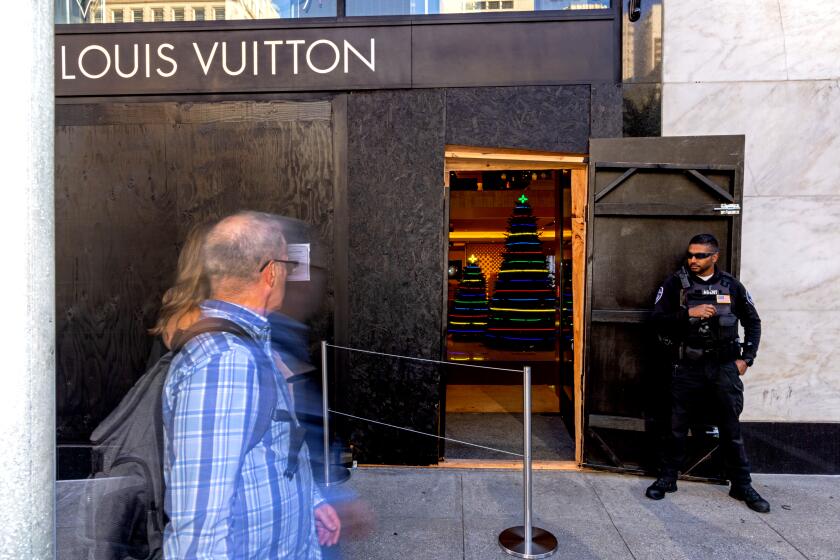

The LAPD recorded an uptick in robberies in some areas, which records obtained by The Times show was caused by shoplifting incidents that resulted in felony charges. Officials say some retailers are asking security guards to be more confrontational with thieves.

Far from being defunded, the department’s multibillion-dollar budget has continued to grow since the mass protests that followed George Floyd‘s murder by Minneapolis police in 2020. In some ways, the LAPD has begun to resemble the streamlined force that some reformers had pushed for. Low-level arrests and traffic stops have plummeted, and staffing shortages have forced the department to focus more on responding to and solving violent crimes.

The LAPD has faced other stretches of diminished staffing. The Watts uprising of 1965 sparked a hiring spree, but then in the late 1970s, after the passage of tax-slashing Proposition 13 squeezed city coffers, the department’s sworn ranks shrank by hundreds of officers. In the years that followed, then-Chief Daryl Gates lobbied to expand the department to 8,500 cops in order to keep up with the city’s population growth. Voters disagreed, repeatedly rejecting a Gates-backed ballot measure to increase police ranks with a flat-fee property tax.

But police hiring picked back up during the height of the war on drugs in the 1980s and again after another inflection point, the unrest that followed the acquittal of four LAPD officers in the 1991 beating of Black motorist Rodney King. Soon after Mayor Richard Riordan swept into office, having run on the promise to restore order in the city by expanding the LAPD to 10,000 officers — a succession of mayors and police chiefs chased that symbolic benchmark for two decades.

Max Felker-Kantor, a Ball State University professor who studies the department’s history, said LAPD officials have often used moments of crisis to “provide a way to make those arguments where we need more police.”

He said officials have long fixated on the department’s size compared with the NYPD and Chicago police, which historically have had more officers to patrol smaller geographic areas. This idea of a chronically understaffed force became deeply “ingrained,” he said, and has influenced the department’s “proactive” style of policing and reliance on technologies such as helicopters and predictive policing software.

The LAPD’s proposed spending plan forecasts adding 585 new recruits next year over 13 academy classes, which amounts to hiring 45 new cops every month — a target the department hasn’t reached in years. Only 21 officers crossed the stage at the most recent academy graduation this month, which was moved indoors because of air quality concerns from the nearby raging wildfires.

Senior LAPD officers who spoke to The Times described a near-constant juggling act of maintaining patrol minimums, which internal documents show entail eight two-person squads in divisions such as Central, Wilshire and Rampart. Having hundreds of officers out on permanent injury or sick leave, plus dozens more detailed to various specialized task forces, has exacerbated the staffing crunch.

Before he became executive director of the L.A. Police Commission, Django Sibley was a beat cop in Hull, Britain. Like most of his colleagues, he didn’t carry a gun.

Experts who study police recruitment say that departments from coast to coast are facing the same problem of losing officers faster than they can replace them. Experts cite heightened scrutiny over officer misconduct, relatively low pay compared with other less dangerous professions and a general lack of interest in long careers in government service as reasons why fewer people are going into law enforcement.

A Reddit page dedicated to LAPD matters offers another explanation: too much red tape during the recruitment process. The forum is dominated by anonymous posts about would-be applicants complaining about waiting months to hear back from background investigators.

Some officials say it’s too early to see the effect of the police raises, saying they are hopeful it will eventually help reverse the department’s staffing losses.

Police Commission President Erroll Southers has said in numerous public appearances that he thinks the department’s strong reputation continues to attract would-be officers, pointing to the record number of applicants in recent months.

“We’re not just taking anybody so I’m OK with that,” Southers said in an interview last year.

Former L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón — who also served previously as a top LAPD official and was involved in the department’s buildup to 10,000 officers in 2011 — said he believes today, as he did back then, that the goal is a “very arbitrary number, without any real science behind it.”

“The reality is that there is no really clear formula that says that this is the number of officers you should have,” he said, pointing to the lack of consensus among experts about what effect police staffing levels have on safety.

At least in the short term, having fewer police officers does not mean costs are being cut. The short-staffed department has ended up spending millions on overtime — and potentially putting it on the hook for costlier future payouts.

LAPD Deputy Chief John McMahon acknowledged that the LAPD is growing smaller, but said that emerging technologies could help improve efficiency as departments are forced to do more with less. The lack of manpower means that officers are tied up on some calls for hours, interviewing witnesses or retrieving surveillance video, he said, leaving little time for the type of “discretionary enforcement” that helps deter criminal activity.

The list of chief candidates reveals who among the LAPD’s top brass angled for the position and sheds light on heavy politicking behind the scenes.

For months, he has lobbied for a real-time crime center, which he says will monitor live video from scores of cameras and license plate readers across the city to provide timely information to police as they respond to emergencies. In recent months, department officials have started to explore the increased use of drones, similar to cities such as Beverly Hills, he said.

Some police watchdog groups, such as the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, are leery of the department’s history of “techno-solutionism” — the idea that all of society’s problems can be solved by digital technology. Left unchecked, they warn, such expansions of police powers have historically led to privacy intrusions and mass surveillance, particularly in communities of color.

McDonnell, the LAPD’s new chief, is among those who have pushed for hiring more officers, while also saying he supports changing how resources are deployed.

During one of his confirmation hearings, McDonnell told the City Council that he wants more cops for “reinforcing” community policing, whichcalls for officers to get out of their vehicles and engage with residents, instead of racing from one 911 call to the next.

“We’re working on a shoestring now,” McDonnell said. “But the efficiency comes at the expense of the community policing philosophy.”

Times staff writer David Zahniser contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.