- Share via

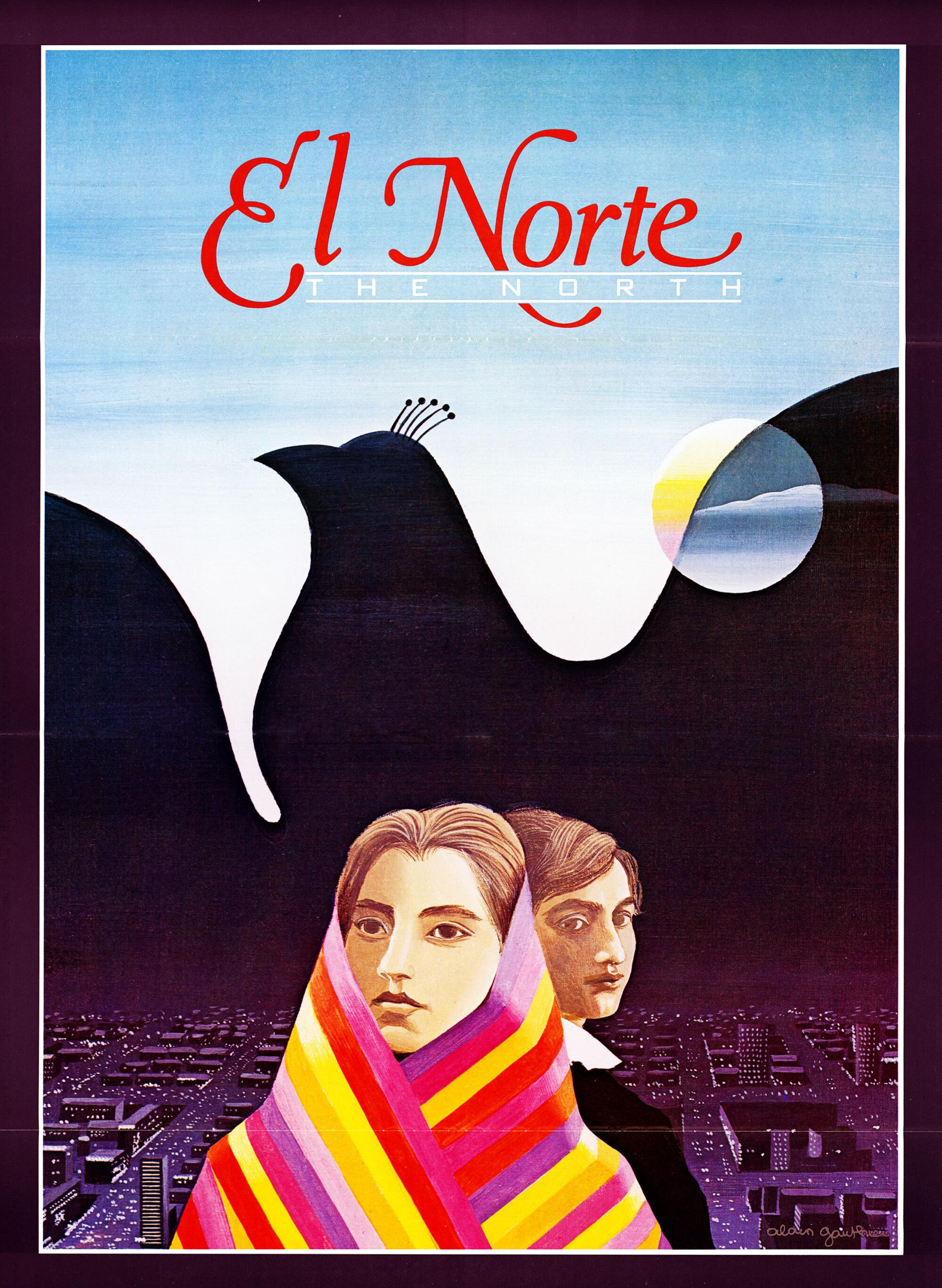

After having celebrated its 40th anniversary last year, the Sundance Film Festival is not yet done looking back at its storied history. In addition to playing over 80 new feature films, the Park City, Utah, fest will once again showcase key films that have shaped the Sundance Institute and independent storytelling in turn. This year that includes a screening of the 1983 film “El Norte,” which played at the festival early Tuesday.

Forty years after it first earned writer-director Gregory Nava and co-writer Anna Thomas an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay, the film remains a new American classic. A sweeping epic about the treacherous journey some migrants make from Central America to the United States in search of a better life, “El Norte” feels just as timely in 2025 as it did when it first premiered.

Nava’s connection to Sundance, both its festival as well as the institute, goes back decades. He was at the very first Sundance Lab in 1981. It’s there where he got to further develop “El Norte,” working with his actors to help hone in on the kind of story he wanted to tell, one as grounded in his own experience of living next to the border, as informed by the vast research he did talking with Central Americans who’d escaped violence in their countries of origin.

“It was an incredible experience,” Nava recalls over Zoom about that filmmaker retreat. “We worked with Sydney Pollack. We worked with Waldo Salt. One of the requests that I made to Sundance was that in order to do ‘El Norte,’ we would have to bring professional actors together with nonactors. So they brought Ivan Passer, the great Czechoslovakian filmmaker who had done ‘Intimate Lighting’ and who really knew how to work with nonactors.”

In casting then-nonprofessional actors Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez and David Villalpando as his two leads, Nava had wanted to bring a level of wounded authenticity to the film. It would be a way to offer a humanist portrayal of people who had often been sidelined even in their own stories.

“Los Angeles was a city pervaded with shadows,” Nava says. “Of people who were picking up your dishes and mowing your lawn and taking care of your babies and doing all the work of the city. And I could tell, I knew, from my background, that they were from Guatemala, they were from Mexico, that they were refugees, that they were people who were here, and that one of them had an epic story”

But Nava knew that to tell such an epic story he’d have to approach it differently than how he’d seen such stories being told in Hollywood. This was a tale that would be grounded not in European story beats but in Indigenous — and Maya, specifically — lore.

“One of the things that I wanted to do when I made ‘El Norte’ was to tell a Latino story in a Latino way,” he says. “I didn’t want to do a movie that was imitative of something else.”

He turned to the great novels from Latin America like Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and Miguel Ángel Asturias’ “El Señor Presidente.” But he went even further back. He drew inspiration from the Popol Vuh, a foundational text for the Kʼicheʼ people of Guatemala. And it was there where he first began toying with the idea of making “El Norte” a story about siblings.

“One of the things that you see in ancient Mesoamerican and Mayan mythology is that they’re always twins,” he explains. “There’s always two, not one. In the Popol Vuh you have Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. And since our protagonists are Mayan I wanted to capture Mayan culture and make it true to Mayan myth and Mayan storytelling.”

“El Norte” is anchored by a brother and a sister. Broken up into three parts (“Arturo Xuncax,” “Coyote” and “El Norte”) the film follows Rosa and Enrique. Played by first-time actors Villalpando and Gutiérrez, the siblings first witness the genocidal violence that’s taken over their small town. Both of their parents are killed by the military. Fearing for their own lives, they decide to trek north in search of a better world. That journey first takes them through Mexico, then through the border, and eventually to a cold and uncaring Los Angeles that chews up their dreams, American and otherwise.

Nava similarly turned to a series of 17th and 18th century Maya texts to dream up different kinds of symbolism that would lend the film a distinct kind of texture. He points to a scene where Rosa finds out her mother has been taken (and likely killed) by armed men. Rather than portray such a violent scene, Nava shows Rosa arriving at her mother’s comal and finding it full of white butterflies.

“In the Chilam Balam, there is this image of whenever there’s a problem in the land — a plague, the Spanish conquest, war with the Itza, people dying, famine — there was a gathering of white butterflies,” he says. “And I read that, and I went, Oh, my God, that is unbelievable. This is our Latino storytelling. In our way. With images that you’ve never seen on the screen before.”

In keeping with that commitment to bringing Maya folklore into “El Norte,” Nava insisted on making the film trilingual: it’s in K’iche’, Spanish and English, truly capturing a journey that’s both geographic and linguistic in equal measure.

As the film moves from Guatemala to Mexico and then to the United States, Nava slowly splinters the magical realism Rosa and Enrique had grown up with. The potent symbolism in their hometown, where their connection with their own dreamlike imagery is central to their everyday lives, soon fades away. As Rosa and Enrique try to make a living as undocumented workers in Los Angeles, the brutal reality around them quickly sets in.

It’s not lost on Nava how prescient the film now feels. At a time when rhetoric about the border and the so-called “migrant crisis” continues unabated, “El Norte’s” focus on the humanity of its Maya protagonists reorients the conversation around the lived experience of those making life or death decisions when they cross the border.

Nava recalls a recent screening of it for students at USC who watched it for the very first time.

“After the film was over, I was crowded with students,” he recalls. “And they said to me, ‘This film seems like it was made last year.’ It was a fantastic experience in a way, to go, ‘Yes, we’ve made a film that has that kind of life and longevity and moves people.’ But by the same token, 40 years on, and the situation is still the same.”

“Because everything that the film is about is once again here with us. All of the issues that you see in the film haven’t gone away. The story of Rosa and Enrique is still the story of all these refugees that are still coming here, seeking a better life in the United States.”

The urgency of its story packs a punch for the shocking image it closes with: a shot of a severed head. It’s a dour note to end on but one that Nava knew would be necessary. It’s why he knew the film would have to be made outside of the studio system and with the backing of institutions like the Sundance Institute and PBS (which partly funded the film). He was committed to offering an unvarnished look at the daily reality of men and women like Rosa and Enrique.

“I wanted to tell the truth,” he says. “Part of the journey of making this movie, and of making it independently, was so you could tell the truth. I can’t put a happy ending on the story of refugees coming to this country. That would be a lie.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.