What’s the use of freedom? A novelist found it while tussling with ‘Free Love’

- Share via

On the Shelf

Free Love

By Tessa Hadley

Harper: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

One 40-year-old housewife’s revolution begins with a kiss in “Free Love,” the eighth novel by British author Tessa Hadley. In 1967, as a misbegotten dinner party winds down in a suburban London backyard, Phyllis Fischer kisses Nicky, the young and insouciant journalist son of family friends, and everything changes. Without hesitation, she abandons her family to live in Nicky’s London cold-water flat atop a dilapidated building of bohemians and immigrants. This act expands into a larger rejection of social systems Phyllis finds morally corrupt. But just as she settles into her new life, a plot twist drives home the inevitable truth that freedom, particularly in middle age, comes at a cost. For Phyllis, it’s worth it.

Melodramatic as this may sound, liberation in the 1960s was a seismic event, especially in stiff-lipped Britain. The personal upheavals of the era marked a dramatic shift from austere, repressive times to the brash, contemporary moment we still inhabit.

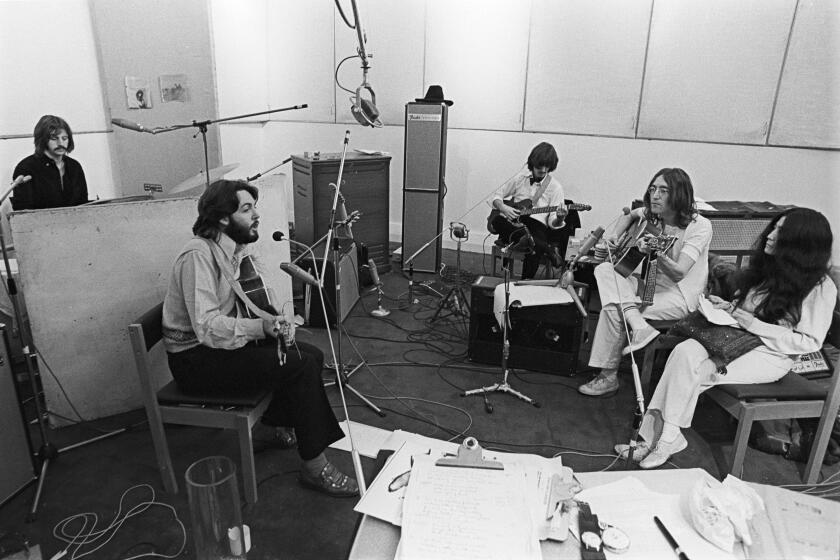

Think of the scenes around the rooftop concert in Peter Jackson’s Beatles documentary, “Get Back.” Hadley watched it with her husband over Christmas. “There are men with umbrellas, expostulating — ‘Can’t we shut them down?’ — because crazy youth with their long hair and their loud music are getting in the way,” she says over Zoom from her home in Cardiff, Wales. It was, she recalls, “a pivot on which the next 60 years hang. We live as the heirs of that moment.”

To fully capture its intensity, Hadley has made her own radical shift: She’s written, for the first time in a while, a linear story within a finite period.

Hadley’s recent novels, including “The London Train” and “The Past,” have been acclaimed for toggling skillfully back and forth in time, the better to illuminate complicated contemporary women in middle age and beyond. What emerged were uncommonly clear psychological portraits of the anxiety surrounding aging, agency, desire, creativity and bourgeois life. Alice Munro and Elizabeth Bowen spring to mind, as do Lily King and Zadie Smith.

The author discusses her quartet of novels, written fast on the heels of Brexit, Trump and the ensuing horrors and concluding with “Summer.”

What links these works to “Free Love,” for all their structural differences, is an invigorating focus on the second half of life, which is when Hadley has produced her most meaningful work. It has been 20 years since she published her first novel, “Accidents in the Home,” at 46. However, midlife reinvention stories like Hadley’s are never simply the magic of overnight success.

“In my first 20 years [as an adult] when I was struggling to write, I didn’t know how to write a book that worked,” Hadley says. “Part of the struggle was my fear, in those days, that the realist novel of the 19th century, which I love to read, might be dead.” The challenge she took decades to resolve was how to meld those realist sensibilities with the modern one. In the 20th century,” she explains, “we learned to be more self-conscious.”

With “Free Love,” she chooses to be direct. Where previous books relied on an accordion-like manipulation of time, the new one aims straight for the bind of middle age. Gone are the historical flashbacks of “Late in the Day” and other novels. In this propulsive new work, the past lives only through the present.

Phyllis races against time to escape regret, seizing a future free from compromise rather than capitulating to inertia and remorse. She flouts convention to abandon one family and then become a mother again at 40. Within the artificial world of fiction, an imagined woman is liberated without punishment, though she is not by any means unscathed. The taste of her hard-fought autonomy is as bitter as it is sweet.

Her heroine’s success hinges on “a kind of foolishness,” Hadley says — and so does the author’s. “If you can’t be naive and risk making a huge fool of yourself, you can only write guarded, smart books. And there’s a place for them, but they’re ephemeral.” She weighs whether it’s “courage or foolishness that enables a writer to be a bit childish in their books” as a means to offset excessive self-awareness. Ultimately, she notes, “it’s always the interplay between these two opposites.”

Hadley gamely exploits this tension in a narrative that grants the reader sympathy for all its characters — the fearless and hidebound alike. Her feat is all the more impressive at a time when critics openly judge harsh mothers. Consider the journalist who recently felt justified asking “Maid” author Stephanie Land if she should have had an abortion.

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

The theme is everywhere. Recent works like Dana Spiotta’s “Wayward,” Claire Vaye Watkins’ “I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” and Maggie Gyllenhaal’s film adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s “The Lost Daughter” resonate with contemporary audiences who connect with ambivalent portraits of motherhood.

Yet, as Hadley well knows, this search for freedom outside the nuclear family is not new. Doris Lessing’s novels on the theme draw on choices she made beginning in the ’30s and ’40s. Hadley latches onto the decade when this became possible without scorn, determined to remain objective throughout. “I really don’t want to take sides about [social] change,” she stresses. “I hope what novels do best is watch the change.”

In Phyllis, Hadley has created a “woman who is not unhappy, not abused, not miserable.” Removing judgment, Hadley frees the reader to fully absorb Phyllis’ motivations. That even-handedness applies to all her characters. Hadley observes: “I think in a novel you can be entirely with Phyllis on one page — feel, as she says, that every cell of my body has changed, and she can’t go back,” yet “also agree with her husband who says, ‘We all live in the same world. How do you think you’re free of those things?’”

Hadley may get to see yet another perspective on the story; “Free Love” has been optioned for television by the Apartment, the outfit that produced an adaptation of Ferrante’s “My Brilliant Friend.” Reflecting on her first screen option, Hadley senses “a gorgeous kind of relinquishment,” anticipating the freedom “to do so much work visually, not spelling things out but hinting, and seeing.”

This sense of relinquishment — of setting aside reason to take up freedom — is what drives Phyllis and also works on her author in the middle of her late career: the freedom from having to polemicize and explain. “The great privilege of the novelist actually — which I believe quite strongly — is that at their best, [one] doesn’t actually need to take sides,” she says.

That doesn’t mean relinquishing tension or pain. Throughout this deceptively straightforward story, an undercurrent of mixed emotions tears at the reader. Personal liberation is not a victimless exercise, but Hadley creates space to see the larger motion of history at the end of an empire — and at the beginning of a freer but more complicated era. Brutal but optimistic, Hadley’s arresting novel offers a backward glance that helps show us a way forward.

Peter Jackson’s nearly eight-hour Beatles doc both refutes the canard of Yoko as band-wrecker and reminds us of what was lost when Paul and John went separate ways.

LeBlanc is a book columnist for the Observer. She lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.