COVID shut down his set. How Paul Schrader finished shooting ‘The Card Counter’ in 5 days

- Share via

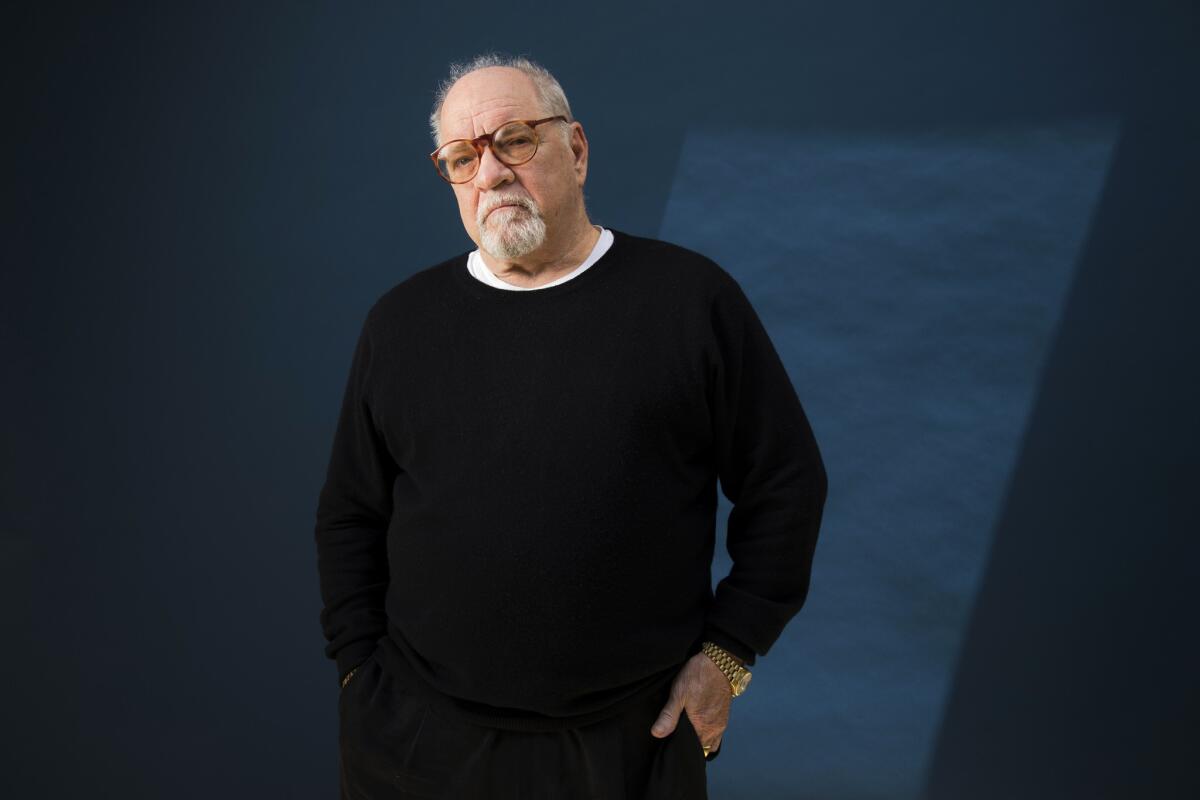

Having somehow weathered his way from enfant terrible to wizened survivor, Paul Schrader is a filmmaker who is simply not finished yet. Every time it might seem his career is on the wane, he resets, revitalizes and comes back again.

Just a few years after his 2014 film “Dying of the Light” starring Nicolas Cage was taken away from him by financiers — leading Schrader to disavow the movie — he received his first Oscar nomination (for original screenplay) after directing “First Reformed,” which was released in 2018 and starred Ethan Hawke as a troubled small-town minister.

Schrader’s work is marked by emotional intensity, intellectual vitality and an aesthete’s appreciation of style. His filmography is full of unusual corners that are still being discovered. The 1979 film “Old Boyfriends,” directed by Joan Tewkesbury with a screenplay by Schrader and his brother Leonard, was recently rereleased on home video. As was the 1990 film “The Comfort of Strangers,” directed by Schrader from a screenplay by Harold Pinter.

He’s been directing films from his own scripts since 1978’s “Blue Collar” starring Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto. He went on to write and direct such films as “Hardcore,” “American Gigolo,” “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters,” “Light Sleeper” and “Affliction.” His celebrated work as a screenwriter for director Martin Scorsese includes “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Bringing Out the Dead.”

Never one to shy from controversy onscreen or off, he directed Lindsay Lohan in the 2013 Hollywood-set thriller “The Canyons,” written by Bret Easton Ellis.

In March, Schrader was about three-quarters through the shoot for his next film, “The Card Counter,” in Mississippi — with a cast that includes Oscar Isaac, Tiffany Haddish, Tye Sheridan and Willem Dafoe — when the production was shut down due to the growing pandemic. In July, Schrader was able to shoot for an additional five days to complete production.

During the break in shooting, “The Card Counter” was picked up for distribution by Focus Features.

Schrader recently got on the phone to talk about the unusual circumstances of the film’s production and completion. A film critic before he became a filmmaker, Schrader not only had startling insights into his work, but also thoughts about what filmmaking and exhibition might be like in a post-COVID world.

Before we start talking about the production on the movie, could you just describe the story? What is “The Card Counter” about?

Well, I don’t want to get too deeply involved in the plot, but what I will say is over the years I’ve kind of developed my own little genre of films. And they usually involve a man alone in a room, wearing a mask, and the mask is his occupation. So it could be a taxi driver, a drug dealer, a gigolo, a reverend, whatever. And I take that character and run it alongside a larger problem, personal or social. It could be debilitating loneliness like in “Taxi Driver.” It could be a midlife crisis like in “Light Sleeper.” It could be an environmental crisis like in “First Reformed.”

So now I have a character and he’s in his room, he’s alone. And he has a mask on. And the mask he wears is a professional poker player. And the problem that runs alongside him is that he is a former torturer for the U.S. government. So it’s a mix of the World Series of Poker and Abu Ghraib.

How did you come to put those two things together?

I’m always looking for that. I’m looking for deep-seated problems, either personal or societal, and some kind of oddball metaphor. The more you get closer, you run these two wires next to each other, the more sparks you see flying across. And it’s in the sparks that the viewer comes alive. If the wires ever touch, there’s nothing left for the viewer to do. But if you keep these two wires really close to each other, the viewer will start to spark from one wire to the other. And that’s the greatest thing you can give a viewer or a reader, an opportunity to be part of the creation.

Let’s talk about the production and everything you’ve been through. Take me back to March. What was it like for you when the production had to shut down?

I have learned in my dotage how to make a quality film on a low budget. So the film I used to make in 40 days I now make in 20. And so “First Reformed” was 20. I had shot in Biloxi 15 days. Now I knew coronavirus was going to be rising, because when I heard that Macau shut down, I said, you know, it’s just a matter of time. Macau is the wealthiest gambling center in the world and I’m here in the gambling center of the Gulf. If Macau shuts down, it’ll reach Vegas, it’ll reach here. And we were doing a scene, a poker tournament with 500 extras. And I remember I said to the A.D., “We can’t put 500 people in a room without one of them being positive.” And sure enough, one of them was. Two days later, we not only closed down, all of the Gulf was closed down.

Fortunately, when I went back, I had shot my big crowd scenes. And also I had shot my sex scenes, which I would have hated to try to do under these restrictions. So all I had left when I went back was a number of scenes in the prisons, and four more scenes in the casinos, some driving scenes. So I was in pretty good shape. But I really wanted to finish the film.

And Oscar Isaac, he was on his way to Hungary to do reshoots for “Dune.” And he wanted to put off this reshoot till after “Dune” — to do it in September because he has a big beard and he didn’t want to shave off his beard. I said to him, “Oscar, there’s a window open right now in Mississippi.” I said, “If we don’t jump into this window while it’s open, this will become one of those famous films that never got finished, and we’ve got to exploit this moment.”

So I talked him off the ledge and he agreed to do it. And we were able to put everybody back together and do our week of prep and five days of shooting. It was very strange, and in a way it was kind of fun, in a summer camp sort of way. But I would hate, hate to make a whole film this way. It was an adventure for five days, it’s a nightmare for five weeks.

It was an adventure for five days, it’s a nightmare for five weeks.

— Paul Schrader on completing “The Card Counter” with post-pandemic safety protocols.

In the break from March to July, were you on high alert that you could come back at any moment? Were you editing the footage you already had?

Here’s what happened. I was editing. My editor is in New Jersey and my assistant editor is in Tennessee, so we’re all editing virtually. And I had four major dialogue scenes between my principal characters that I had not shot. Then I was able to screen virtually the film for a number of people I respect, like Scorsese, who is the executive producer, like [filmmaker and programmer] Kent Jones and other people. And what I asked them all is, “I have four more scenes to shoot. I can rewrite them. What am I missing? What do I need to add? How should I write these four scenes?”

And I started getting feedback about what they felt was missing. So I was able to rewrite these scenes and make these relationships much better. And not all productions get to do that. It’s a very expensive reshoot, but it was built-in that three-quarters of the way through, I have an opportunity to rewrite one-quarter of the meaningful character scenes. So I did, I rewrote it. And I realized what was missing. And I wouldn’t have realized that if I was shooting at the top. I would have only realized that in post. And I would have walked around the room kicking myself in the ass, saying, “I wish I had the opportunity to reshoot some scenes.”

How was getting everything back together?

As soon as Mississippi allowed us to come back, we came back. And of course nobody’s working, so everybody’s eager to come back. They are hyper-conscientious because they know they are only being allowed to work by the grace of God. And so the masks and the PPE and the hands and the distancing, you don’t need to tell any of the people this. They’re so happy to be at work. They have no problem with any of that.

You can only have one person within six feet of your actor at a time. That person could be hair, it could be makeup, it could be props, it can be the director, it could be another actor. And you kind of queue up. And a thing that I realized, we had a warehouse. So we did rehearsals for every scene in this warehouse. And I told the actors that when we get to the location, to the casino, the prop people will be in there, the lighting people will be there and then you will walk there with your mask on, and you will take the positions that you took in rehearsal. Then I will roll camera and you will take your masks off and we’ll play the scenes. So that’s how we did it.

Given everything that it takes to get to shooting, once you were back on set with the actors, did you still feel like they could give you the performances that you needed? Was it difficult to get to a place of artistic creation given all the other concerns that everyone has?

Because they had done the rehearsals, they had gone through the permutations of their performances before. So the only thing different for them was that they were in a real space rather than a fake space. As I explained to them, there would be no time for exploration on set. All the exploration you are going to do, we’re going to do here in the warehouse. I don’t want to hear one peep from you about changing anything once we get into this hothouse environment. So however many hours we have to spend in the warehouse, let’s spend it.

How close to finished are you with the movie now, considering you had a lot of it already cut together?

Basically, I’m finished, down to an hour and 49 minutes, which is where I think it should be. Obviously, I have to do the score, there’s the post-prod and the special effects, but the thing is that there’s no pressure to finish the film anymore at this time. I was talking to Focus, and I could give them the film in a month. They don’t want the film in a month because they don’t know what to do with it in a month. They said, you just take whatever time you need, which is the opposite of the way studios usually talk. I also have final cut, so it doesn’t really matter. What I deliver, I deliver.

When you made “The Canyons” you talked a lot about your feelings regarding the theatrical experience, VOD and streaming and contemporary filmmaking. What impact do you think the COVID shutdowns will have on movie theaters?

There’s a certain kind of film like “The Canyons,” which should be made for VOD, which is a kind of exploitation film. And there’s another kind of film like “First Reformed” that has to be mounted by film festivals and art-house cinemas, so that it has an identity prior to VOD. So if you’re on VOD and you see an Ethan Hawke film about a minister, you’re not going to say, “Oh, let’s watch that.” No, what you’re going to say is, “Oh, I heard about that film. I heard it was good.” Well, how did they hear it was good? They heard that from film festival reportage and they heard from their friends who have seen it at theaters. So that sets up VOD.

The opposite case is a film like “First Cow,” a film that was crushed by not having a theatrical window. And everybody is, “Should I watch ‘First Cow’?” They have no context. So what’s important for a film like “The Card Counter” is we have to give it context. We have to go to the festivals and we have to go to the art cinemas to tell people what we have in our hands. Then we can go to VOD, where the real money is. So “First Reformed” went to Telluride, Toronto, Venice and New York. That set the table. I would love to set the table for this one. I can go to all those festivals. That’s not a problem for me anymore. The problem is: Are festivals going to happen?

Do you think theaters are going to come back?

Not in the way they did. There are only four reasons for theaters to exist anymore. And this situation has accelerated these trends. Like symphonies and operas and live theater, concerts, they need a reason to exist. One reason is family cinema, because parents love to see their kids interacting with other kids. Animation films will always have an audience. Another is extraordinary spectacle. IMAX, virtual, whatever they come up with. Something you can’t see at home. The third is date movies for high schoolers, which is horror and rom-coms. Or rather, dirty rom-coms.

And then the fourth is club cinema. Which used to be called art cinema. But with these new institutions that are a combination of social institutions and cinematic institutions. So the Metrograph in New York has one restaurants and two bars. There’s more square footage devoted to eating and drinking than there is to watching movies. And yet it’s always full because people want to be in that environment. So then alcohol’s become the new popcorn. And those club cinemas, which were pioneered by Alamo, they will continue to exist because people want to be part of the club, people want to buy a membership. They want to eat and hang out, and they want to know which films have been approved by the club. Which is something you cannot get from VOD.

When “First Reformed” was coming out, you spoke about how you had made it thinking it could be your last film. And yet you seem so reenergized over the last few years. Do you feel that way? Have you been able to hit the reset button in some way?

Oddly, yes. I’m in the middle of a new script, which is about a horticulturalist. And what has happened in my case, following the disastrous situation I went through with “Dying of the Light,” I said, I would no longer work unless I had final cut. And once I got final cut, I was free. When I began, you didn’t really need final cut. When I was working in the studio system, all those other films, you were working with people who knew movies, who liked movies. Who you can talk to, you could disagree with — things would get changed, sometimes they’d get better, sometimes for worse in your mind, but you were working with people who liked movies, who watched movies. In the last 15 years, I’m dealing mainly with financiers, who not only don’t watch movies, don’t even particularly like them. And how can you have discussions with these people? And that’s what final cut freed me from, because I realized I couldn’t talk to these people. I wasn’t talking to [studio executives like] Barry Diller and Thom Mount and Ned Tanen anymore. I was talking to Joe Schmo from some hedge fund and I couldn’t talk to Joe Schmo. The only way I could talk to him was to have final cut.

I’m certainly excited to see what becomes of “The Card Counter.”

The new one is quite good. Focus told me not to hump it too much because that’s their job down the line. But you can take my word for it, it’s quite good.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.