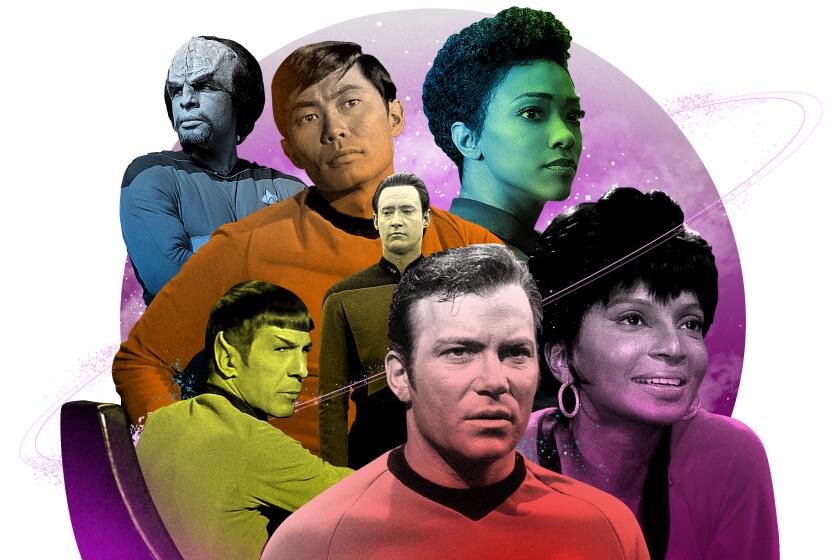

Appreciation: ‘Star Trek’ underutilized Nichelle Nichols. She was its heart and soul anyway

- Share via

The original “Star Trek” may have been canceled in 1969, but it is still with us. That three seasons of a television series could in those days produce 79 episodes led to a healthy life in syndication, which brought the voyagers of the starship Enterprise new generations of viewers and led to the creation of a dedicated fandom, multiple ongoing conventions and the eventual creation of a franchise that continues to pay respect to the original.

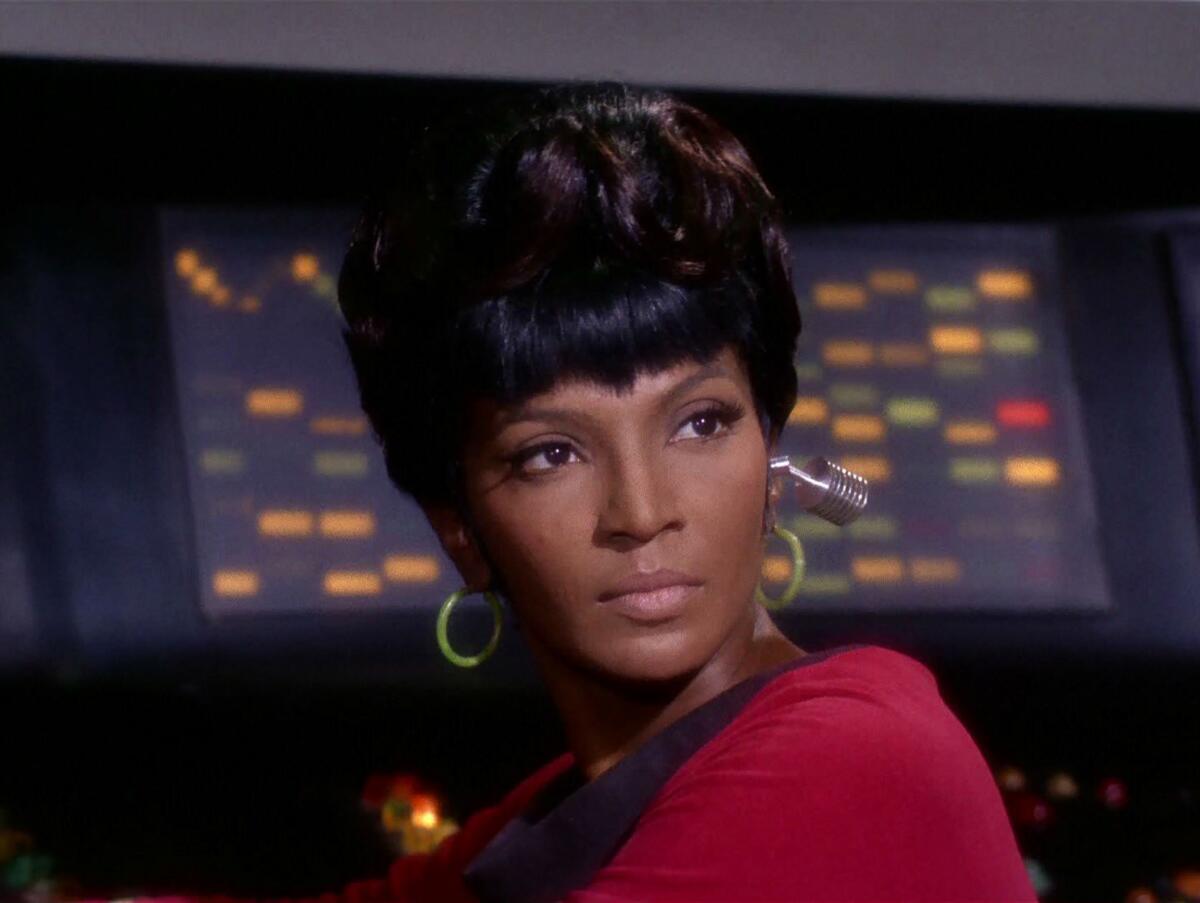

As communications officer Lt. Uhura (the first name Nyota was a later addition), Nichelle Nichols, who died Saturday at the age of 89, was with the show from first to last, including the subsequent “Star Trek: The Animated Series” and six feature films built around the original cast. Nichols was an elegant, poised performer — she was a trained dancer who held herself like one, just sitting at her console, one leg forward, one leg back, one hand to her earpiece — and in a series in which overacting can sometimes seem like the baseline, she never did too much. But Uhura was far more than a character in a television show, just as Nichols was something more than an actor: They were inspirational figures of historical import, both the player and the part, models of dignity who pointed to a better future simply by doing their jobs.

While racism was a recurring theme on “Star Trek,” Earth in the 23rd century is portrayed as having moved beyond prejudice, and so within the context of the series there is nothing extraordinary about a Black woman in a position of responsibility — Nichols has described Uhura as “fourth in command” — which is exactly what made it extraordinary in the context of late-1960s television.

Nichols died of heart failure Saturday night at a hospital in Silver City, N.M.

“Where I come from, size, shape or color make no difference,” William Shatner’s Kirk tells little person Michael Dunn in “Plato’s Stepchildren,” the third-season episode in which Kirk and Uhura have their famous kiss — not television’s first interracial kiss, it has been pointed out, but as far as I can tell, the first between a Black woman and a white man. The fact that they’re forced into it by telekinetic aliens, robbing them of agency, makes the scene no less groundbreaking, and Uhura’s speech to Kirk just beforehand puts a deeper slant on things: “I’m thinking of all the times on the Enterprise when I was scared to death. And I would see you so busy at your command. And I would hear your voice from all parts of the ship. And my fears would fade. And now [the aliens] are making me tremble. But I’m not afraid.“

Kiss aside, there’s no question Nichols was underused in the series; in the hierarchy of the show, in terms of screen time, there are Kirk and Spock, and then McCoy and Scott, and then Uhura (and Sulu and Chekhov). A lot of dudes. (Majel Barrett’s recurring Nurse Chapel was the only other female element, notwithstanding various guest aliens, often scantily clad.) Uhura rarely joins a landing party. But even when she’s not the focus of a scene, she is regularly onscreen, even if just visible at her post on the bridge, completing the picture, contributing to the emotional tenor. (And when she isn’t there, you notice it.) As the communications officer, everything runs through Uhura: She’s the voice of what’s happening elsewhere on the ship, and what’s happening outside the ship, whether announcing the presence of some other spacecraft or relating what’s up with Planet X. Even reciting lines like “I’m receiving Class Two signals from the Romulan vessel” or “Revised estimate on cloud visual contact 3.7 minutes,” she is the picture of the professional. She builds exposition, asks important questions; wordlessly reacting to some bit of business on the viewing screen, she brings an emotion and energy into the scene different from that of her sometimes blustery male colleagues.

Still, in the series’ first episode, Uhura confesses that she’s “beginning to feel too much a part of that communications console.” And whenever she’s liberated from her post for a minute and allowed to do anything else at all, you notice and remember. Whether she’s in a crawl space rigging up a subspace bypass circuit, or speaking teasingly with Spock (“Why don’t you tell me I’m an attractive young lady or ask me if I’ve ever been in love? Tell me how your planet Vulcan looks on a lazy evening when the moon is full”), or pretending to be an evil mirror-universe version of herself, these excursions leave you wanting more. For all it accomplished, the series missed a few tricks when it came to Nichols.

There was more to her than “Star Trek,” before, after and during. A performer since her teens, Nichols had toured as a dancer (and at least one night as a replacement singer) with Duke Ellington and made her screen debut in the 1959 film of “Porgy and Bess.” She had originally set her sights on a career in musical theater. You get a glimpse of that performer in the series’ second episode, when, as Spock plays on his Vulcan lyre, Uhura begins to mischievously sing and move catlike through the ship’s lounge: “Oh, on the Starship Enterprise / There’s someone who’s in Satan’s guise / Whose devil ears and devil eyes / Could rip your heart from you.” (Nichols got a couple more chances to sing in the series and performed a fan dance in “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.”) It was to take a part in a Broadway-bound play that Nichols decided to leave the series after its first season, only to be persuaded to stay after an oft-recounted chance meeting with self-professed huge fan Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who, she later recalled, told her: “For the first time on television, we will be seen as we should be seen every day, as intelligent, quality, beautiful people who can sing, dance and can go to space.”

Full of ideas and emotions, the ever-expanding ‘Star Trek’ canon is still finding new ways to go where no TV show has gone before, 55 years on.

Apart from “Star Trek” films, which commenced in 1979, a decade after the series was canceled, Nichols continued sporadically to act, including episodes of “Heroes,” “Downward Dog” and “The Young and the Restless,” and movies of varying budget and quality, including Disney’s “Snow Dogs” and the zombie film “The Supernaturals”; perhaps her least Uhura-esque role is in the 1974 Isaac Hayes blaxploitation film “Truck Turner,” in which she plays an ice-cold, highly profane madam. (In 2008, she’d play another madam, a friendly one, in “Lady Magdalene’s,” a ridiculous low-budget action comedy.) Whatever the vehicle, her work always feels committed and self-assured.

But “Star Trek” remains her legacy, and her gift, and it shaped her life, leading Nichols to work with NASA, recruiting women and people of color to the space program (as recounted in the 2019 documentary “Woman in Motion”). Finally, it was home. In the 2007 feature-length fan film “Star Trek: Of Men and Gods,” directed by “Star Trek: Voyager” actor Tim Russ and also starring Nichols’ old castmate Walter “Chekhov” Koenig, Nichols played Uhura one final time, in a part that — with no Kirk, no Spock in the way — at last brought her to center stage. Currently available on YouTube, the film definitely feels homemade, but it is clearly a labor of love, and Nichols, white-haired and still beautiful, is wonderful in it. And Uhura still lives, in the person of Celia Rose Gooding, who plays the character’s younger self in “Star Trek: Strange New Worlds.” These days, “Trek” women get a lot to do. And often they are women of color.

“I believe it was fated,” Nichols said in a Television Academy interview of the encounter with Dr. King that sent her back to “Star Trek.” ”And I’ve never looked back, I never regretted it. Because I understood the universe had somehow, that universal mind had somehow put me there. And we have choices — are we going to walk down this road or are we going to walk down the other? And it was the right road for me.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.