Celebrity Access Shuttered

- Share via

After the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Jim Smeal’s phone didn’t ring for two weeks. The fax machine stopped spitting out press releases and party invitations. The e-mails dried up. Even when the clatter resumed, all he could hear was the sound of lost opportunity.

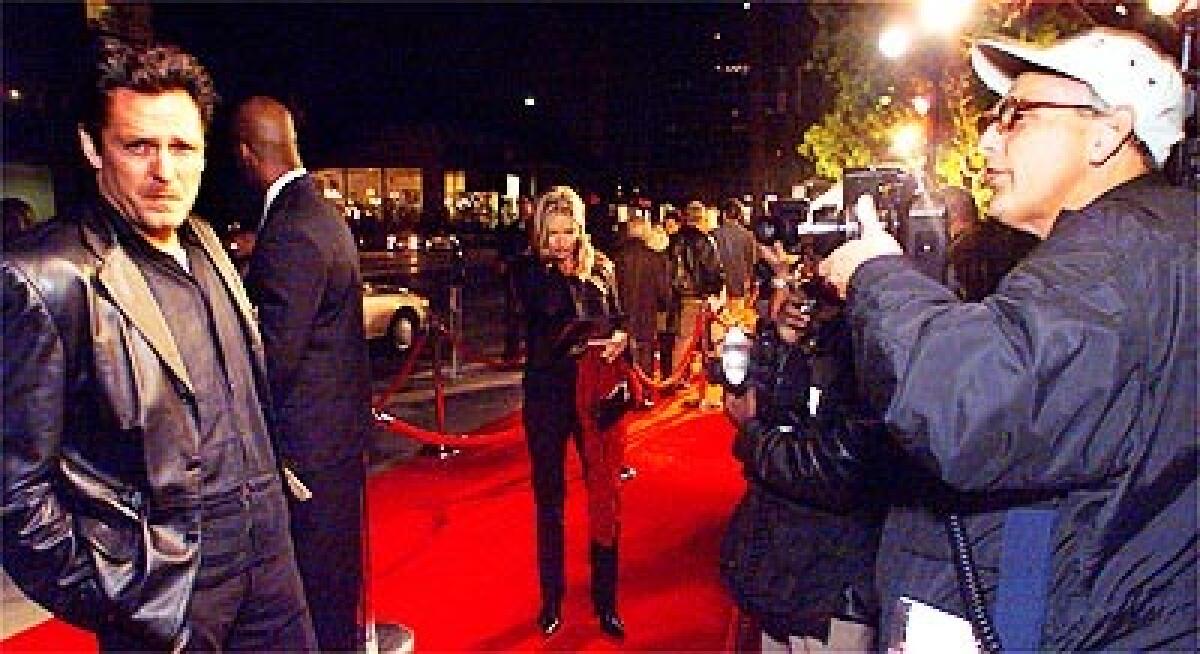

Smeal makes a living taking pictures of the stars who stroll Hollywood’s red carpet at movie premieres, charity fund-raisers and awards shows. He started September booked solid. Then, suddenly, the party was over.

Now that Hollywood is slowly rolling out the red carpet again, Smeal finds he’s persona non grata.

Among other events, the paparazzi weren’t invited to the Los Angeles premieres of Ben Stiller’s “Zoolander,” Mariah Carey’s “Glitter” and Michael Douglas’ “Don’t Say a Word.”

For the first time in 16 years, Smeal and his camera-toting colleagues were denied access as the stars arrived at the Shubert Theatre on Nov. 4 for the Prime Time Emmy Awards show. There simply wasn’t enough room for everyone, they were told.

Terrorism, war and fear of anthrax have wrought a major shift in the tense but symbiotic relationship between the ubiquitous paparazzi and Hollywood’s establishment, including the film studios, celebrities and publicists.

Increased security means smaller events--and less room for the paparazzi, who feed off the glamour but also help perpetuate it.

Like everyone else, the photographers are learning to live with intrusions such as having their backgrounds checked and their bags repeatedly searched. But they also gripe that security concerns have given movie studios and party organizers an excuse to restrict access. By excluding photographers they don’t like or can’t control, the studios can further influence the images that shape a celebrity-smitten culture.

“This is worse than Diana, big time,” Smeal said, referring to the backlash against the paparazzi who were following the princess of Wales in Paris in 1997 when she was killed in a car crash. “That was over in a month and a half. This isn’t going to be changing any time soon.”

The studio publicists, reluctant to speak on the record about anything related to security, deny they’re playing favorites. The rules changed when the world changed on Sept. 11, they say, and they owe it to the stars, the fans and even the photographers to keep everyone safe.

“The security is real for us,” said Geoffrey Godsick, director of publicity for 20th Century Fox. He said the Los Angeles Police Department has asked the studios to admit only credentialed photographers.

But the LAPD, which has conducted background checks and handed out its lime-green press passes to about 4,000 media representatives working in the city, won’t credential the entertainment media.

So the photographers are scrambling to establish an acceptable credential while they negotiate with the studios for better access.

A group of celebrity photographers already has formed an association that would issue credentials to members. To qualify, a photographer must demonstrate a track record--showing samples of his or her work in a major publication--win sponsorship by two charter members and submit to a background check.

In pre-Sept. 11 Los Angeles, more than 50 freelance and agency photographers could be found on any given night outside posh hotels in Beverly Hills, theaters in Westwood and hip nightclubs in West Hollywood. These are the regulars, mostly male and middle-age, and they provide a scruffy contrast to the glitz as they bark orders to the preening stars.

The work can be lucrative. During the prime party season, January through March, Smeal said, he can make $20,000 a month. He’s neither the highest-paid nor the lowest-paid photographer on the line.

These photographers long have bristled at being called paparazzi, preferring to separate themselves from the more aggressive of their craft, the long-lens cowboys who stake out their famous targets at home, at playgrounds, outside supermarkets and, occasionally, exiting the plastic surgeon’s office. Instead, they prefer to identify themselves as “red carpet” or “event” photographers.

But as far as the celebrity publicists are concerned, they take and sell pictures of movie, television and pop stars, and that makes them paparazzi.

The paparazzi genre was born Aug. 15, 1958, when one photographer snapped a grainy picture of another being throttled by an exiled playboy king at an outdoor cafe in Rome. Italian film director Federico Fellini used the scene in 1960’s “La Dolce Vita,” giving the photographer the name “Mr. Paparazzo,” after an annoying childhood friend.

More recently, paparazzo “just became a generic term for anyone who owned a camera who wasn’t on staff somewhere,” publicist Stan Rosenfield said.

Smeal, for example, is paid a base salary by Ron Gallela Ltd., the agency run by New York’s most notorious paparazzo. On top of his salary, Smeal makes commissions every time one of his shots is reprinted--say, for a magazine’s annual best- or worst-dressed list. The commissions helped him weather a weak September.

Out of desperation, Smeal and other paparazzi started showing up at smaller events they previously would have ignored. “I’m getting tired of shooting B-listers,” one complained in a New York-accented growl, standing outside a private home in Bel-Air on a recent Saturday night. “B-listers?” cracked another. “All I saw this week were C-listers and D-listers.”

They complained bitterly that chilly night about how the studios were using the crisis to exclude all but a few favored shooters. Among the favored is Alex Berliner, who runs Berliner Studios--founded three decades ago by his father. Berliner also works weddings, anniversary parties, bar mitzvahs--often for some very famous clients. And he is hired by the studios to photograph their events. He was the only photographer invited to the first few low-key Hollywood events after Sept. 11.

“Alex Berliner has the whole town sewn up,” said Caroline Graham, West Coast editor of Talk magazine, which is partially owned by Miramax Films. Miramax uses Berliner exclusively at its events, she said. “He has all the parties wired, and Hollywood is happy with it that way.” If anything, she said, Sept. 11 “probably improved his position. He’s now top dog, Super Dog.”

The other dogs are howling.

“You’re taking food from my mouth!” one freelancer complained to a 20th Century Fox publicist when there was no space for him on the red carpet at the Westwood premiere of “Shallow Hal,” starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Jack Black. The harried publicist warned she was in no mood for guilt trips or squabbling. It is a privilege, not a right to work the red carpet, she scolded, according to photographers who were there.

“There’s always been a lot of pushing, shoving, definitely a lot of backstabbing” among the red carpet photographers, Smeal said. “Lots of it. I’m not saying I’m an angel; I’ve been part of it. When things are not going great, everybody fights.”

Now, the photographers have tossed aside old rivalries and are working together to soothe the studios’ security concerns. If they don’t, they fear, “the studios will take over,” Smeal said.

He and Kathy Hutchins, who runs her own photo agency in Burbank, are so fiercely competitive they hadn’t spoken in years--until Smeal picked up the phone to enlist her help after Sept. 11. “I said, ‘We’ve got to do something about this.’ ”

They sent an open letter to the major studios and public relations firms, saying that “serious consequences have become immediately apparent to those of us who have supported the entertainment industry with publicity.”

The pair protested the “limiting or eliminating” of freelancers at events, pointing out that the “select” photographers who are given access aren’t interested in “the more obscure celebrities.” Security, they said, “is not automatically created by eliminating our coverage of events.”

On Oct. 15, the red-carpet photographers gathered, 40 strong, at Jerry’s Famous Deli on Beverly Boulevard to organize. Admittedly, it’s an endeavor comparable to herding cats. “We have a group of people who can’t even agree on the color of vanilla ice cream,” Hutchins said. But when they met again a month later, their ranks had grown to 60.

Elected to the board of the new association, L.A. Event Photographers, were Hutchins, Smeal, Fitzroy Barrett, Janet Gough, Paul Smith and Steve Granitz, the paparazzo responsible for a memorable shot of Tom and Penelope--Cruise and Cruz--leaving Spago after a lunch date.

The photographers agreed to work with security consultant Ralph Pipes, owner of Special Event Management, a company that provides security at about 400 events each year. Pipes had attended an earlier meeting at which the LAPD discussed security issues with Paramount, MGM, DreamWorks, Disney, 20th Century Fox, Universal and Warner Bros. He volunteered to work with the studios and photographers to set up a system both sides could live with.

The LAPD and the studios, Pipes said, “wanted to know who’s standing along the line.” It had become “very lax” and unmanageable, he said. Just five years ago, he said, “there would be between eight and 10 TV crews and maybe 15 photographers, and that was considered a big event. Today, we’ll have between 25 and 30 crews and between 40 and 50 photographers.”

The photographers agreed with Pipes to police themselves. With his help, they’ll arrange for background checks for members and issue identification cards. The cards should be ready by mid-December.

“All this is basically doing is giving each studio a comfort level,” Pipes said. “At a high-profile event, it’s nice to know who’s there.”

Granitz said he welcomes the background checks because they will weed out the riffraff. “We’re there to do a job,” he said. “The photographers have had problems as well. You don’t know who’s standing next to you. . . . Suddenly, something will be missing, like your lenses.”

Times staff writer Louise Roug contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.