A well-rounded genius

- Share via

While thumbing through the weekend real estate ads six years ago, Steve Roden spotted a curious listing: Architect Wallace Neff’s last personal residence, the Shell House, was on the market in Pasadena. For $289,000, the buyer could own a 1,000-square-foot domed structure built out of gunite, rebar and concrete.

The World War II-era house — designed by Neff as an experiment in affordable housing — came with interesting amenities: a large cone-shaped fireplace and thick exterior walls to deflect cold, heat, termites, bombs and shrapnel.

Roden, an artist who had been searching for a modern house with his wife, Sari, for more than a year, had never heard of Neff, renowned for building Spanish Colonial Revival style houses for wealthy and famous California clients. Even so, Roden was intrigued.

“I kept thinking, ‘the Shell House? What is that?’ ” he said. “I figured, well, it’s under $300,000 so I’ll drive by it.” From the outside, the place didn’t look like much. Hidden behind a thick stand of mature trees in a neighborhood of wood-sided bungalows, it resembled a giant mud cake. “The outside was different, but nondescript. I went home and told Sari, ‘We have to go see this house because I can’t imagine what it looks like on the inside.’ ”

The couple set up an appointment with Crosby Doe, the real estate agent who was handling the listing. “We opened the front door,” Roden said, “and it was like we were stepping into the New York World Fair’s House of Tomorrow.” The home’s curved interior walls were 7 feet high while the domed ceiling stretched to 12 feet, giving the tiny house a feeling of space and openness. “It’s a little like being inside of an upside-down swimming pool.” Roden and his wife promptly abandoned their search for a square, modernist house, bought the property for $260,000 and moved in, inheriting a cache of vintage furnishings that once belonged to the architect. They even found a large pottery bowl, made by Neff, in the garden.

Since moving into the house in 1998, the 39-year-old artist has become an expert on the architect’s quest to address the global housing crisis by building domed structures — often referred to as shell, balloon or bubble houses. Although Neff built similar houses all over the world, few are still standing. The Pasadena Shell House — which will be featured on a tour of six Neff homes on March 28 — is the last remaining structure of its kind in the United States.

“It’s a little like being the caretaker of someone’s project,” said Roden, who is hoping to get a historic designation for the property. “The truth is, this house doesn’t really fit into the rest of Neff’s work. People who love his work don’t really appreciate it. And people who would appreciate it don’t because Neff wasn’t a hipster, or they don’t know about it.”

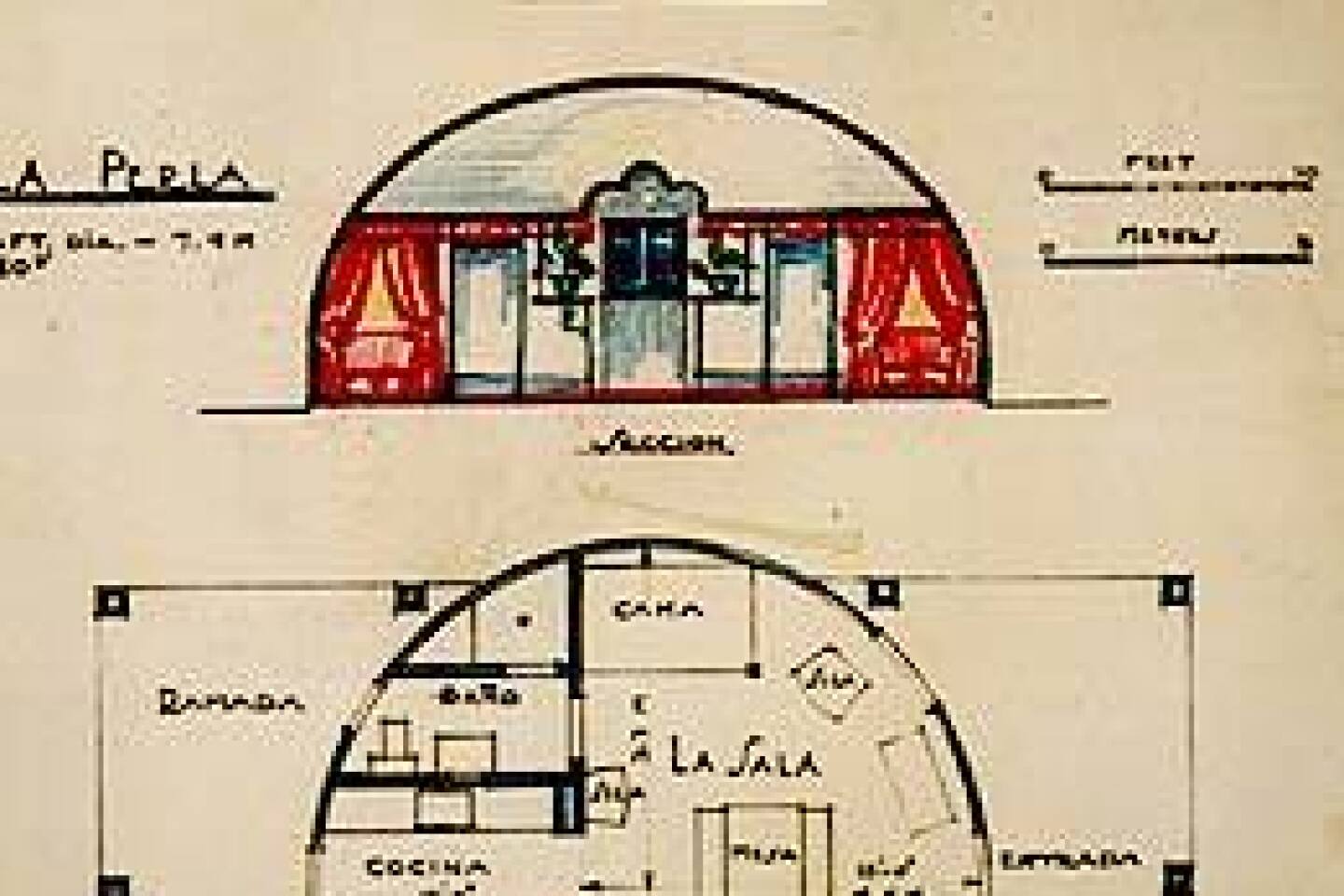

Neff began building the concrete structures, which he would call “airform construction,” in 1941. The airform construction technique is relatively simple. It requires inflating a giant, rubber coated balloon and then spraying it with gunite. Once the gunite is set, the balloon is deflated and removed though a door or window. The house is then insulated, reinforced with rebar and covered with another layer of concrete.

The architect’s first bubble house was built in Falls Church, Va., where it was used as housing for defense workers and other people displaced by the war. The following year, it was used as company housing for the Goodyear Rubber Co. — which manufactured the giant balloon used in the construction process — in Litchfield, Ariz. Neff also built similar houses in Mexico, Africa, South America and the Middle East.

The Pasadena house, designed for his brother, Andrew, is the largest and most sophisticated of all of the architect’s airform structures. Stories about the house abound.

“We heard that Elvis was in this house, I assume meeting with Neff about building him a mansion,” Roden said. “We heard that Gandhi was in this house. I don’t know how or when that would have been possible. There’s so many stories. This place is such a novelty.”

According to the book “Wallace Neff 1895-1982,” printed by Hennessey + Ingalls in 1998, Neff was seeking not only to make a major modernist statement but also to “resolve the dilemma of being an architect close to affluent clients and a designer for a mass of anonymous clients with low budgets.” It came as no surprise that Neff had taken a keen interest in dealing with world housing issues. As the grandson of Andrew McNally, the cartographer who founded Rand McNally and developed La Mirada and Altadena, he came from a family of forward thinkers

“There are a lot of architects with unique ideas on how to deal with the housing crisis,” said Doe, who has sold numerous Neff houses to celebrities in Southern California over the years. “This was Neff’s answer. It really is Wallace Neff at his most creative.”

During the 1940s, Neff said he simply found the design of his bubble houses aesthetically pleasing. “Beautiful flowing lines and curves come into being without effort . The absolute absence of girders, columns, and jigsaw trusses, startles the imagination,” he wrote in an article for Architectural Forum.

Doe lived just blocks from the Shell House when it was constructed in 1946. “I would have been about 6 years old when that house was built,” he said. “To a young child, it was like a colony had landed from Mars. It indelibly set in my mind the uniqueness.”

In addition to the domed structures, Neff also built his so-called “honeymoon cottage,” a name coined by one of the architect’s famous clients, Mary Pickford. The houses were mass-produced, portable and made to withstand earthquakes and storms. At the time, Neff said he was “possessed by the thought that there should be a demand for small homes of real charm within the reach of people of limited means.”

He told a Pasadena Historical Society panel in 1977 that he especially believed the bubble houses had “tremendous possibilities.”

“I always thought people would come rushing in by the thousands to buy houses,” Neff said. “But it never happened.”

By the mid-1980s, almost all of the architect’s airform homes had been destroyed, in many cases to make way for new development. Neff sold the Pasadena Shell House in the late 1970s when he moved to an assisted living facility, where he stayed until his death in 1982.

Although the Rodens say they were fortunate to buy the two-bedroom house at the bottom of the housing market six years ago, it is probably worth more than double the asking price now — far from the affordable housing unit that Neff had envisioned.

“We feel lucky to be here,” said Sari, a jewelry designer. “It’s like living in a sculpture, yet it’s very homey.”

They have kept the home largely unchanged, using old photographs as their guide. Almost all the furnishings are from the mid-1940s.

Neff left behind a curved sectional couch, which Roden recently re-covered in vintage red wool. The large curved living and dining area is also accented with a George Nelson for Herman Miller lighted end table, an Alvar Aalto circular side table and Eugene Deutch pottery. The dining table is by Able Sorensen for Knoll, the chairs by Eero Saarinen. George Nelson bubble lamps are on a ledge near the sculptural, circular fireplace, which Roden calls “the human sacrifice pit.”

An area of black concrete — an original detail that was uncovered by the Rodens after carpet and plaster were removed — surrounds the fireplace. Handcrafted wood cabinets hug the curved walls.

Roden — who shows his abstract paintings, drawings, sculptures and sound installations in galleries worldwide — has added a number of other details, including 1950s art by Ossip Zadkine and Irv Wyner and a collection of pottery found at flea markets. Two months ago, he spotted a large ceramic bowl at the Long Beach flea market that looked much like the one he had found in his frontyard. He turned it over to see if it was signed. It said, simply, “Neff.”

“Apparently Neff and his brother had tried to do this decorative pottery thing,” Roden said. “But you never see that referenced in any of the books about Neff.” He paid $60 for the bowl and took it home.

Roden views the flea-market find as symbolic of his and Sari’s experience as the self-described caretakers of the Shell House.

“If someday someone found all my work at the flea market, I hope they would take care of it and read some catalogs and try to do the right thing,” Roden said. “This house is something Neff believed in. I feel so strongly about his dream of what this thing could have been.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.