Eroni Kumana dies at 93; helped rescue JFK and his PT-109 crew

- Share via

On a moonless night in the summer of 1943, a Japanese destroyer tore through a U.S. Navy patrol-torpedo boat guarding the waters around the Solomon Islands. The boat was PT-109, skippered by a young lieutenant from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy.

Two of Kennedy’s 13 men were killed in the collision, and others were injured or sickened by the fuel that poured from their sinking vessel. Desperate for refuge, they swam for five hours to reach a small island. One man was so badly burned that Kennedy towed him with the strap from the wounded sailor’s life jacket clamped in his teeth.

Over the next days Kennedy returned repeatedly to the water, swimming past exhaustion in the hope he could spot rescuers and lead them to his battered crew. To improve their chances, he moved them to a larger island, but they were plagued by hunger, thirst and fear that Japanese forces would find them. They didn’t know the Navy had given them up for dead.

Their story might have ended there. That it didn’t was due in no small part to Solomon Islands native Eroni Kumana.

Kumana, who helped save the future president and his crew, died Aug. 2, six days shy of the 71st anniversary of their rescue. He was believed to be 93.

His death in the western province of the Solomon Islands was announced by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. No cause was given.

Kumana was barely out of his teens when World War II came to his corner of the world. Thousands of Japanese troops were garrisoned in the Solomons and depended on supplies from the “Tokyo Express,” a convoy of Japanese warships that made regular runs through Blackett Strait in the western Solomons.

PT-109 was part of a squadron patrolling the strait on the night of Aug. 1, 1943, when the Tokyo Express came steaming through. The Navy boats fired 30 torpedoes, none of which struck. All of the boats returned to base except for three that still had torpedoes. Kennedy’s boat was one of them.

Around 2 a.m. another Japanese destroyer, running without lights, suddenly appeared, headed straight for PT-109. With only one engine going to minimize detection, the Navy boat could not power up fast enough to avoid catastrophe. As the destroyer sliced through the boat, Kennedy lost the wheel. “In a moment he found himself on his back on the deck, looking up at the destroyer as it passed through his boat,” journalist John Hersey wrote in a famous account for the New Yorker in 1944.

The other boats took off, assuming that everyone on PT-109 perished in the huge fireball caused by the crash. Back at base, a memorial service was held.

Others had heard the explosion, including another young islander named Biuku Gasa, who worked with Kumana as a scout for an Australian coast-watcher helping the Allies. The coast-watcher instructed them to search for survivors.

On the fifth day after PT-109’s demise, Kennedy and one of his men left the others on Olasana Island and swam to the next island, Nauru, where they found the wreck of a Japanese vessel and some provisions.

More exciting, however, was the sight of two islanders on the beach. Kennedy shouted for their attention, but they fled in fright.

The two natives were Kumana and Gasa.

“We thought they were Japanese and we ran away,” Kumana recalled through a translator in the 2002 National Geographic film “The Search for Kennedy’s PT-109.”

He and Gasa paddled off in their canoe but made a fortuitous rest stop — at Olasana Island. There they discovered the other crew members, who convinced the pair they were Americans.

“Some of them cried, and some of them came and shook our hands,” Kumana said in an oral history. When Kennedy arrived, he embraced the island scouts.

He wanted them to take a message to his superiors. Lacking paper, Gasa suggested Kennedy use a coconut, so Kumana plucked one from a nearby tree.

Kennedy carved these words on the shell:

NAURO ISL.

COMMANDER...NATIVE KNOWS

POS’IT...HE CAN PILOT...11 ALIVE

NEED SMALL BOAT...KENNEDY

Kumana and Gasa paddled 38 miles at great risk through Japanese-controlled waters to deliver the message to the coast-watcher, who then radioed the news to the Navy squadron commander on Rendova Island. Two rescue boats brought PT-109’s survivors to the base early on the morning of Aug. 8.

Kennedy’s heroic actions to save his crew became central to his political success. After winning the presidency, he invited Kumana and Gasa to his inauguration in 1961, but British colonial officials blocked the trip. Kumana later told interviewers it was because neither he nor Gasa spoke English.

When Kumana learned of the president’s assassination in 1963, “I sat down ... and cried,” he recalled in the National Geographic film. He built a shrine to the late president near his home on Ranongga Island and named his son John F. Kennedy.

The coconut was preserved as a paperweight that Kennedy used in the Oval Office and now is kept at the presidential library.

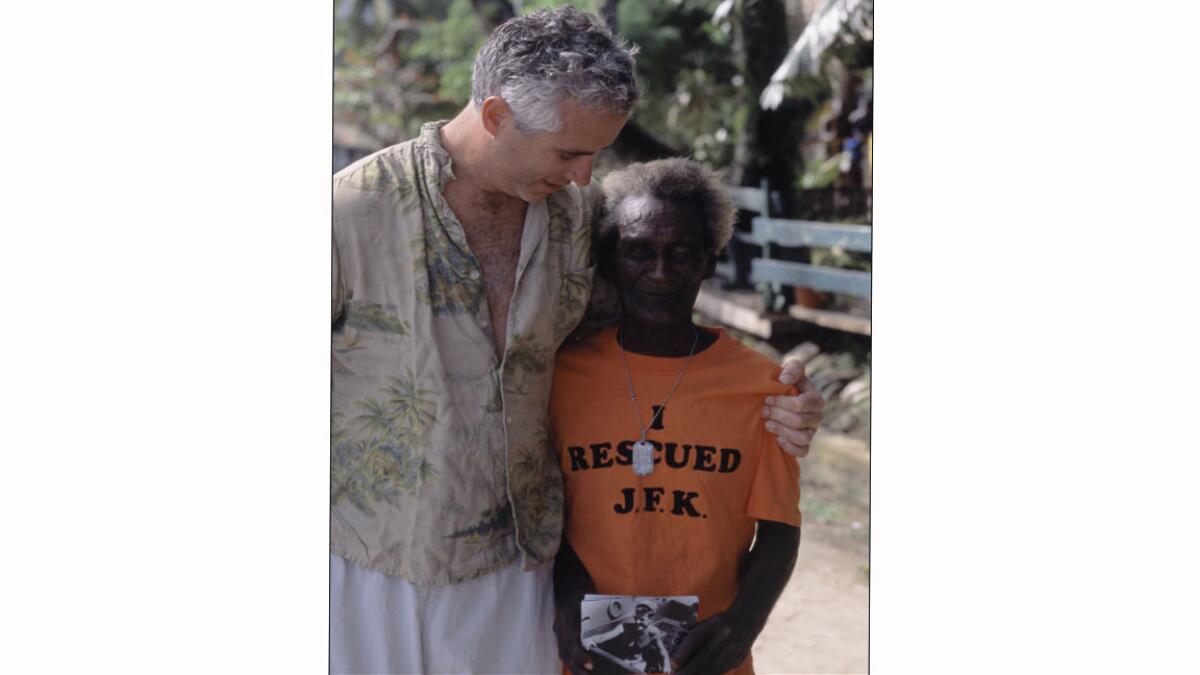

In 2002, Max Kennedy, one of the sons of Kennedy’s brother Robert, traveled to the Solomons with the National Geographic expedition to meet the islanders whose courage he had heard about since childhood. In an emotional high point in the film, Kumana sobs as the younger Kennedy embraces him.

Max Kennedy presented Kumana and Gasa with gifts, including a letter from another brother, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, who wrote that President Kennedy “never forgot you.”

“Both of them were extraordinarily charismatic men,” Max Kennedy said this week about Kumana and Gasa, who died in 2005.

He described the day he spent with Kumana as full of laughter.

“He was very, very funny and had a great sense of irony, which I think President Kennedy also had,” Max Kennedy said. “He was wearing a T-shirt that is very popular in the Solomon Islands. It read ‘I Rescued JFK.’”

Twitter: @ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.