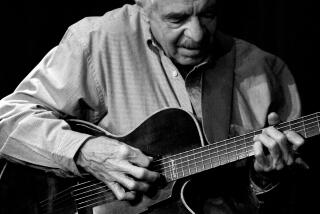

Ira Gitler, jazz historian and critic who chronicled the rise of bebop, dies at 90

- Share via

Ira Gitler -- who turned his childhood obsession with jazz into a career as a major behind-the-scenes figure as a critic, magazine editor, record producer and historian who documented the rise of modern jazz -- died Saturday at a nursing center in Manhattan. He was 90.

He had heart surgery five years ago, but the immediate cause of death was not known, his son, Fitz Gitler, said.

Gitler began writing about jazz while in high school in New York -- he covered a performance by bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie -- and later became a fixture at Prestige Records, where he helped produce albums by Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

Gitler wrote some of the first liner notes to be included on an album jacket, for “Swingin’ With Zoot Sims” (1951). In his notes accompanying John Coltrane’s 1958 album “Soultrane,” Gitler coined the term “sheets of sound” to describe the saxophonist’s cascading torrent of notes that could practically overwhelm a listener.

In addition to writing two books on jazz history, Gitler helped Leonard Feather, the longtime jazz critic at the Los Angeles Times, compile the comprehensive “Encyclopedia of Jazz,” first published in 1960. After Feather’s death, Gitler took over as primary editor of a revised 1999 edition, retitled “The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz.”

At various times, he was the New York editor of DownBeat magazine, a jazz concert producer and a professor at several colleges. For his varied contributions, Gitler was named a 2017 Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts, the country’s most prestigious honor in jazz.

“Most of all, Ira’s a witness,” critic Gary Giddins said at the 2017 Jazz Masters tribute concert at the Kennedy Center. “When you read an Ira Gitler review, you can agree or disagree, that’s immaterial. But you know it’s sincere, it’s smart, it’s deft, and it’s always discerning.”

Throughout his life, Gitler had a parallel career as a leading authority on ice hockey. He wrote several books on the sport, contributed articles frequently to the New York Rangers program and was a co-author of a 1969 history, “Hockey! The Story of the World’s Fastest Sport.”

It’s safe to say that many people who knew Gitler from either jazz or hockey had no idea that he was an expert in a completely different field.

“He saw certain similarities between jazz and hockey,” Fitz Gitler said in an interview. “Both required you to improvise at an up-tempo speed.”

Gitler was an amateur hockey player and coach into his 70s. His team, Gitler’s Gorillas, won many championships in a New York amateur league and was featured in the New Yorker magazine.

Nonetheless, he was better known for his contributions to music. Working for the Prestige label in 1953, Gitler produced the only recording session that featured Davis, Rollins and bebop innovator Charlie Parker. Because Parker was under contract to another label, he performed under the name “Charlie Chan” and played tenor saxophone instead of his customary alto.

Other recordings Gitler produced, including the Modern Jazz Quartet’s “Django” and several by Monk, Rollins and Davis, have become jazz classics.

Gitler’s first book, “Jazz Masters of the Forties” (later republished as “The Masters of Bebop”), chronicled the emergence of the dynamic music whose major innovators included Parker, Gillespie and Monk.

In his 1985 book, “Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition in Jazz in the 1940s,” Gitler wove together interviews with more than 60 musicians to describe how the dance-oriented swing music of the 1930s evolved into the more cerebral, musically daring bebop a decade later.

For Gitler, the book was the result of a lifelong devotion to the music and the people who made it.

“Bebop was characterized as weird but, to many, it was a music that lifted one with beauty and joy,” he wrote in “Swing to Bop.” “It was an expression of the finest black musical minds and, besides what it expressed explicitly, offered the human verities that jazz had communicated from its inception.”

Ira Gitler was born Dec. 18, 1928, in Brooklyn. His father worked in a family fur business and his mother was a homemaker.

Beginning at age 5, he studied piano with a cousin, composer Elie Siegmeister. Gitler later learned the alto saxophone. As a student at the University of Missouri, he often spent weekends at jazz clubs in St. Louis, Kansas City, Mo., and Chicago. He returned to New York in 1950 without a degree and began working for Prestige.

Gitler had stints as DownBeat’s New York editor in the 1960s and was the host of several radio programs. He taught jazz history at New York’s City College, the Mannes School of Music and, for 20 years, at the Manhattan School of Music, where he would teach students who would become jazz musicians.

He had his crotchets and blind spots, once panning Dave Brubeck’s classic recording “Take Five” in a review. Another time, his complaints about the political message in an album by singer Abbey Lincoln led DownBeat to call a conference on the issues surrounding jazz and race.

Survivors include his wife of 46 years, artist Mary Jo Schwalbach of New York; his son, Fitz Gitler; and two grandchildren.

Gitler often said he became interested in jazz as a child while listening to his older brother’s record collection. He began attending concerts and nightclubs while still in his teens and never hesitated to approach his musical heroes.

“I think the reason I embraced it quickly,” Gitler wrote in “Swing to Bop,” “was because I recognized all the qualities it had maintained from the previous jazz styles that I had been brought up on and loved so much: rhythmic propulsion and the happy-sad duality of the blues that infused so much of the music.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.