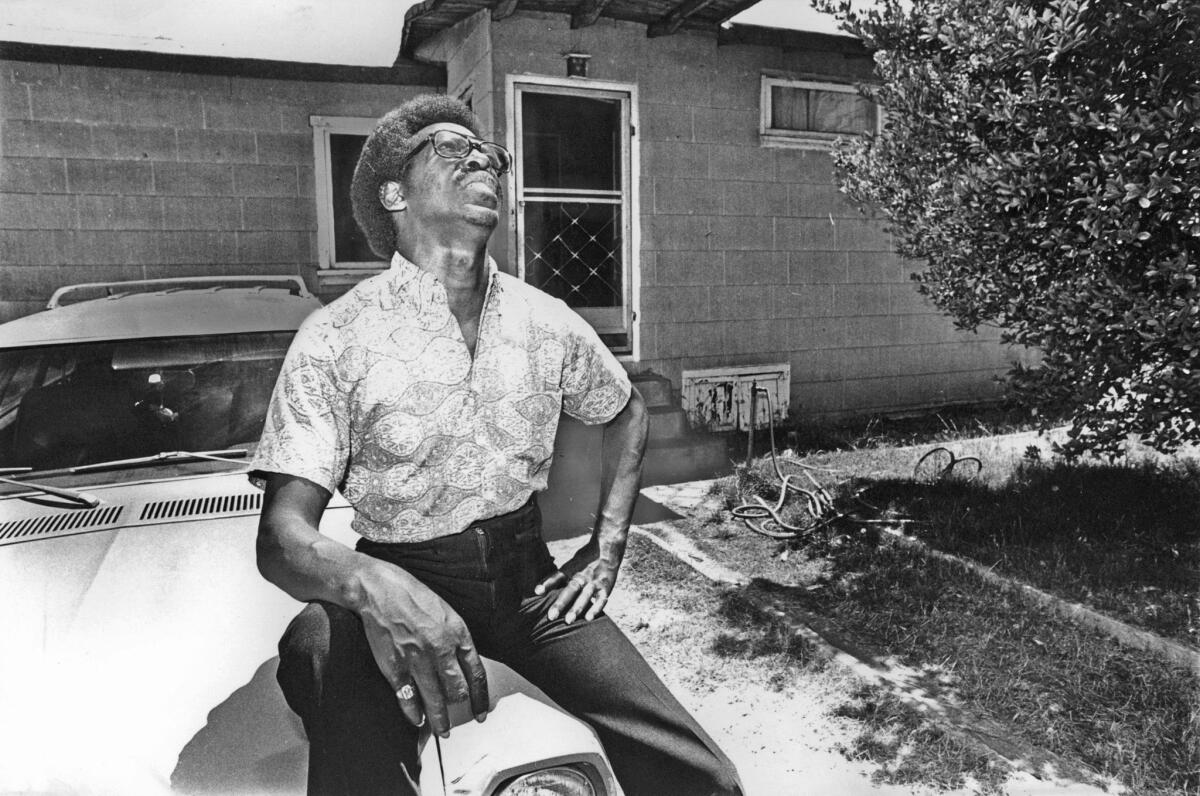

From the Archives: Marquette Frye, Whose Arrest Ignited the Watts Riots in 1965, Dies at Age 42

Marquette Frye, seen in 1980. His arrest sparked the 1965 Watts Riots. He died of pneumonia at the age of 42.

- Share via

Marquette Frye, whose arrest as a 21-year-old suspected drunk driver set off the Watts riots on Aug. 11, 1965, and whose later life was to become as tragic as the riots themselves, is dead of pneumonia, the coroner’s office reported Wednesday.

Frye, who was 42 and had been using his stepfather’s name, Price, because of the notoriety that nagged at him for the last 20 years, was found dead in his home on West 102nd Street last Saturday. Because the body was first identified as that of Marquette Price, Frye’s real identity was not realized until Wednesday.

And it was an identity that had haunted him since that sticky summer afternoon more than 20 years ago when he and his brother were driving along Avalon Boulevard in South-Central Los Angeles.

As he neared 116th Street, Officer Lee Minikus said he saw the car weave and pulled it over. Frye, in a jovial mood, admitted having a few drinks but told the officer that he was only trying to dodge potholes in the road.

Witnesses were later to recount that both the officer and Frye initially were joking with each other. Minikus acknowledged that “everything was doing just fine until his mother got there.”

What followed is still subject to debate, but most accounts reflect that Rena Frye hollered at her son for being drunk, that Frye then began to resist arrest and that someone shoved his mother.

Whatever the scenario, it proved deadly as rumors began to fly about Frye or his mother or both being brutalized by police. Frye himself, in a 1980 interview, said he remembered some of his friends saying as he was being led away: “Don’t worry; we’re going to burn this mother down.”

It proved a deadly prophetic comment.

Six days later, when peace was finally restored by police and the National Guard, the riot’s toll stood at 35 dead, 864 injured, thousands arrested and property damage of more than $200 million.

Those were the collective statistics. The individual damage to Frye was also devastating.

Superior Court Judge Stanley Malone, who as an attorney represented Frye, called him “a perfect example of a young black man who has been done in by society.”

‘Bright and Articulate’

Malone saw his client as “bright and articulate,” but because of the degree of visibility that stalked him after the Watts riot, “whatever possibility Marquette had of rising above his situation was beaten out of him. . . .”

Malone and Frye claimed that in the years immediately after the riot, police would arrest the then-young man on unlikely charges and when he was in custody, beat him and spray him with Mace. In return, Frye spoke at rallies and on television, becoming an embittered example of existence in the ghetto.

Then, as the races moved closer together in recent years, Frye’s popularity waned.

“It wasn’t cool to associate with Marquette,” said Tommy Jacquette, organizer of the Watts Summer Festival. “People said he was a troublemaker.”

Frye was arrested 28 times on a variety of charges, but the police were not his only real or imagined demons.

A son died, and Frye tried to kill himself with a knife. His health deteriorated, and he was forced on state disability.

And he died at only 42, seeing himself as an unwilling symbol, a man made old before his time. He had also grown to fervently wish that it had been someone else behind the wheel of the car on that long ago August day.

“It just happened to me, and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.