Goldberg: Sci-fi worthy of Malthus

- Share via

In the new sci-fi movie “Oblivion,” Earth’s most precious resource is Tom Cruise. But running a close second (spoiler alert) is water. Aliens want it. All of it.

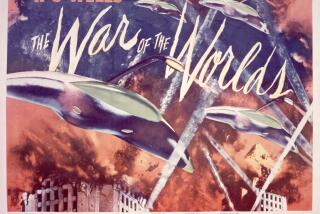

This is old hat, science fiction-wise. In “The War of the Worlds,” H.G. Wells had Martians coming to Earth to quench their thirst. The extraterrestrial lizards (cleverly disguised as human catalog models) in the 1980s TV series “V” came here to steal our water too — though they wanted it in part to wash down the meal they intended to make of us. In the more recent “Battle: Los Angeles,” pillaging Earth’s oceans was the only motivation we’re given for why aliens were laying waste to humanity.

The first problem with this plot device is that it’s pretty dumb. Hydrogen and oxygen are two of the most common elements in the universe. An alien race is savvy enough to master interstellar travel but too clueless to combine two Hs with one O to form H2O? C’mon.

At least in “Mars Needs Women,” the precious resource in question — Earth girls — by definition can be found only here, just as “real” Champagne must come from the region that bears its name. And though I have no doubt that Earth women really are the best, the logic of evolution suggests that compatibility issues for aliens would be a hurdle not even Match.com could overcome.

In “To Serve Man,” the famous “Twilight Zone” episode, the motivation was far more plausible: They wanted to eat us (“To Serve Man” — it’s a cookbook!). And who knows — maybe we’re delicious.

One rule of thumb in sci-fi is that the aliens are really us too. They reflect a good trait in humanity — think E.T., Spock or Mork — or a bad one. That’s why writers recycle ancient human motives — the desire to plunder, colonize, rape, enslave — as the motives of futuristic aliens.

That’s all fine. But science fiction is also supposed to raise ambitions for what humans can accomplish. And in that, Hollywood is failing.

For a while now, filmmakers have been churning out fare — like the horrendous remake of “The Day the Earth Stood Still” — based on the Malthusian assumption that resources are finite and if we keep going the way we are, the Earth will be “used up” (to borrow a phrase from the opening monologue of the canceled cult sensation “Firefly”). Either that or we’ll be invaded by aliens who appreciate our stuff more than we do.

The pessimism is infectious. Physicist and sci-fi nerd Stephen Hawking recently argued that maybe we should hide from aliens lest they rob us blind. When Newt Gingrich proposed a base on the moon, everyone guffawed as if such an optimistic ambition was absurd. The obsession with “peak oil” and the need to embrace “renewables” because we’re running out of fossil fuels are other symptoms of our malaise. Fracking and other breakthroughs demonstrate that, at least so far, whatever energy scarcity we’ve had has been imposed by policy, not nature.

Which gets us back to outer space. In our neighborhood alone, there are thousands of asteroids with enormous riches — in gold, platinum, rare earth metals, etc. Planetary Resources Inc., an asteroid mining firm started last year by director James Cameron (ironic given the politics of his film “Avatar”) and some Microsoft and Google billionaires, has its sights on several rocks worth anywhere from hundreds of billions to tens of trillions of dollars. And these are just the chunks scattered around our orbital backyard and near enough to exploit with existing technology. There are also plenty of balls of ice out there that might be convertible into fuel for further space exploration.

Thomas Malthus and his intellectual descendants saw humans as voracious consumers of finite resources, like a “virus” devouring its host, as Agent Smith says in “The Matrix.” But humans are better understood as creators who’ve consistently solved the problems of scarcity by inventing or discovering new paths to abundance. As the late anti-Malthusian hero Julian Simon said, human imagination is the ultimate resource.

Unfortunately, that resource is dismayingly scarce these days, in Washington and Hollywood.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.