Op-Ed: The need for radical transparency on U.S. torture

- Share via

Here’s a radical idea: Let the people decide.

Since the release of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on torture last week, we have been treated to a predictable barrage of overheated hyperbole. The left says the CIA program was utterly pointless and needlessly brutal; the right says it was completely successful and entirely appropriate. Many have demanded prosecutions; many more have attacked the report as partisan and incomplete. Both sides squared off before most had even read the report, let alone studied it closely.

And even if people had access to it, they would be studying a heavily redacted summary of a much larger report that remains secret. There are no plans to release the rest of the report or to reveal the content of the redactions. More important, no one — as far as I know — has even suggested releasing the underlying documentation so people could form their own conclusions.

And so we are left with a bitter but inconclusive debate about one of the most important programs in our nation’s history.

But what if, instead of vapid finger-pointing, we let the American people figure it out for themselves? What if we gathered everything about the program — not just the summary but the entire report, as well as all the underlying documentation — and let Americans make up their minds? What if, in other words, we tried radical transparency instead of mindless partisanship?

Scholars would probably take the deepest dives. Sociologists, political scientists, historians, psychologists and legal academics could plumb the depths of the material for decades, mining it for countless invaluable insights about the nature of the United States and the world in the 21st century.

Journalists also would be interested and could fill in gaps in the record, not simply by asking the questions they are paid to ask, but by digging deeper and unearthing the humanity of the men and women touched by the torture program. They’d thereby put a human face on the report’s lifeless bureaucratic prose.

But in many ways, the professionals are the least important audience. It would be valuable for high school students writing term papers, elementary school teachers developing lesson plans and just plain curious Americans who want to figure things out for themselves rather than be told what to think by talking heads on TV. This is the audience that matters. The knowledge would be available to everyone.

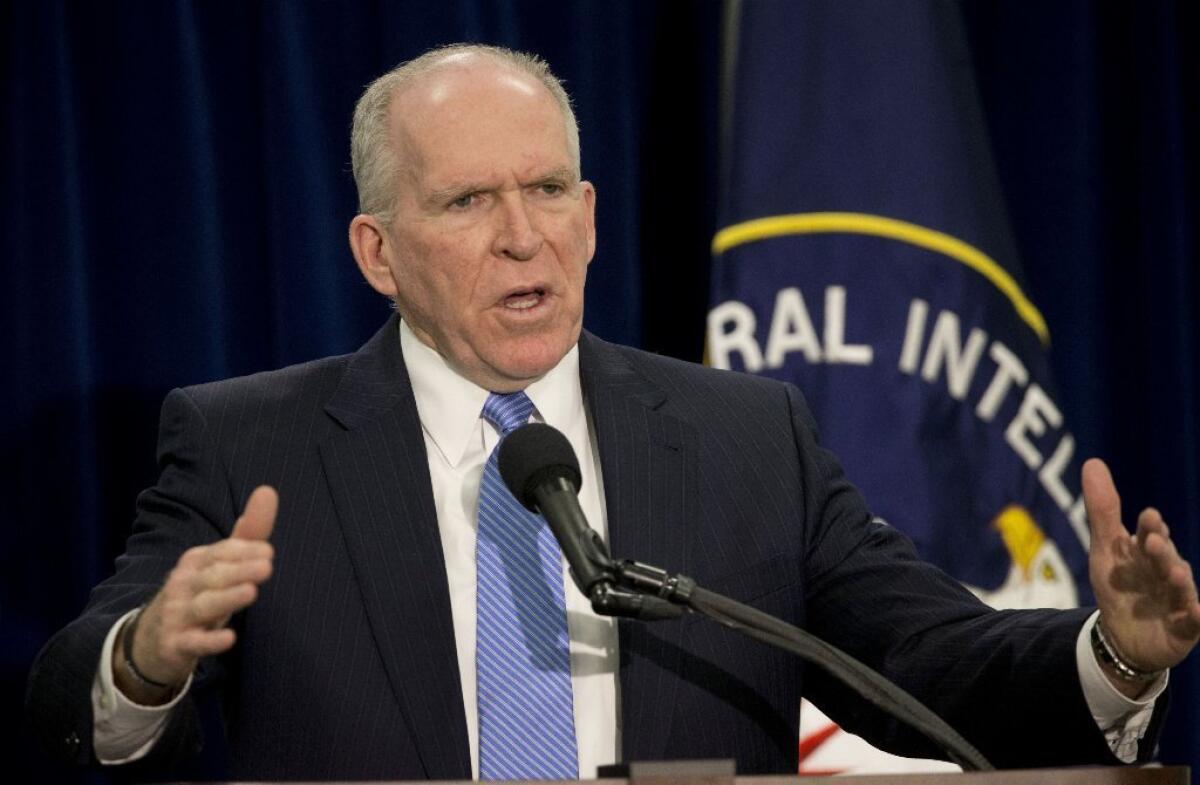

Surely much of this material could be made available immediately. When CIA Director John Brennan addressed the report he emphasized that the episode was long past and encouraged the country to move on. The program ended years ago and the techniques are no longer in use.

Indeed, the CIA insisted on redacting names and places that are already known. Psychologist James Mitchell, for instance, is one of the two principal architects of the “enhanced interrogation” program. He has given a number of interviews freely acknowledging his role, yet his name is redacted in the report or a pseudonym is used.

This is not a technologically challenging project. Virtually all this material is digitized, which means it can be organized and easily searched. Nor would it be particularly expensive to do.

So, is there any chance of this happening? Absolutely not. The odds of meaningful transparency surrounding this program are zero. In the United States today, no major political actor and precious few media outlets are interested in transparent debate about contentious issues. We should pay close attention to this resistance because it reveals something important about the nature of American democracy.

Selective dissemination of the sort surrounding the torture report encourages partisan finger-pointing. From the perspective of the major political parties, this has the salutary effect of invigorating their core constituencies. To put it plainly, selective dissemination gets those who care to care even more.

And since the major parties depend on these people for money and support, there is a chronic demand that the core stay molten hot. The parties thus have no incentive to encourage transparency because it tends to reveal nuances and complexity and therefore appeals primarily to the more moderate, and politically disengaged, middle.

The result is a predictable polarization. Elites within each party who espouse the most radical views become the media darlings du jour, which encourages them to swing for the fences in their public remarks. Fed a diet of raw meat, the energized extremes within each party grow increasingly enraged at the apparent depravity and evident hubris of the opposition.

The result? Dick Cheney, the man the left loves to hate, makes the run of TV talk shows gleefully assuring the faithful he would do it all again. Cue applause.

Radical transparency is not just a campaign slogan. It is a prescription for democratic repair. And that’s a pill the major parties will never swallow.

Joseph Margulies, a visiting professor of law and government at Cornell University, is counsel for Abu Zubaydah.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.