Editorial: Jailed Angelenos die, deputies shrug. Will this daily routine never end?

- Share via

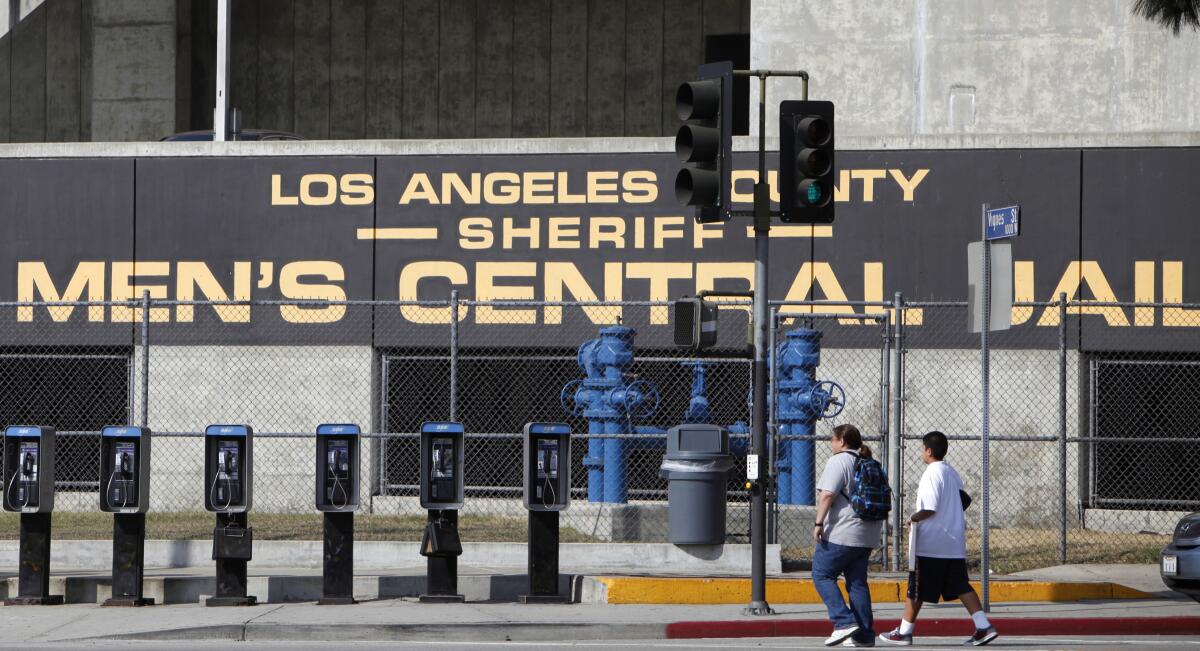

A man was beaten to death in Men’s Central Jail in June, and much to our collective shame, that’s hardly news. So far this year, 37 people have died in Los Angeles County jails.

The particularly noteworthy aspect about the killing of Masoud Rahmati is that for nearly four hours, sheriff’s deputies failed to notice he had been badly hurt and was dying.

In a news article on Thursday, Times staff writer Keri Blakinger reported that jail oversight inspectors had been sounding alarms for months about a lack of supervision in the dorm where Rahmati was attacked in the shower, beaten and then dragged to his bunk.

Political cowardice has given us a half-century of increasingly inhuman incarceration conditions and has diminished safety both inside and outside Los Angeles County jails.

Another man died of suicide in the adjacent Twin Towers jail last month. In a story in L.A. Public Press on Saturday, Emily Elena Dugdale reported that deputies who should have been walking the corridors every half-hour to check on the welfare of the incarcerated men, such as the man who died, were allegedly watching internet videos on county computers instead.

Streaming movies rather than conducting mandatory welfare checks may have been standard operating procedure in the jail. Dugdale cited a July report by the Sybil Brand Commission on Institutional Inspections — the county’s civilian body that inspects jails and reports to county leaders about conditions — that describes deputies bantering with inspectors about the movie they were watching while on shift, apparently unashamed that they weren’t doing their assigned rounds.

The decrepit lockup facility was to close today under Board of Supervisors’ two-year timeline, but it remains full with no end in sight.

The Sheriff’s Department has now reportedly restricted streaming in parts of the jail. That’s the least it can do, though it’s not enough.

The complex of Los Angeles County jails has been a cruel and violent place for so long that deadly conditions are too often ignored as merely routine. A consent decree resulting from a lawsuit filed nearly half a century ago remains in place but manages the crisis without ending it.

A Citizens Commission on Jail Violence sounded the alarm a decade ago and recommended steps to remedy the problem, but the end result is merely a jail where deputies themselves inflict less violence on people in custody, but appear to have little motivation to protect them. The Sybil Brand Commission and the grand jury repeatedly report horrendous conditions to the Board of Supervisors to little effect.

Cruel summer heat turns non-air-conditioned concrete prisons into ovens that cook the people inside alive. This is not justice. It is inhumane.

County officials note, correctly, that people die in jail all over the nation. Jails house many people who arrive in poor physical or mental health or are prone to violence and other predatory and antisocial behavior.

But rather than excusing the appalling conditions in Los Angeles, the fact of inhumane incarceration around the nation is merely a reminder of the widespread failure of the U.S. jail system. A civilized society has an obligation to provide a level of safe and appropriate care to those who are so sick, marginalized or uncontrollable that, at least for a time, they cannot live unsupervised.

The Sheriff’s Department has pleaded poverty, arguing that it could not fulfill its responsibility to those in its custody without additional funding for personnel and overtime. But there appears to be a cultural problem that more staff and dollars will not solve. The deaths and the inspectors’ reports suggest that the department is failing not because there are too few deputies to do the work, but because there is little understanding of the work that must be done. More deputies watching videos for more hours, obviously, would not enhance the safety of the jail for the incarcerated.

Nor is the problem a lack of oversight. There is abundant oversight. The Sybil Brand Commission could better document failures if it could conduct inspections more frequently, but the problems it has already noted ought to be sufficiently alarming to spur immediate change. Instead, its reports are little heeded.

There is a deficit of humanity, and a lack of acknowledgment that we and our institutions have a duty of care to people in jail. It would be foolish to believe that the contempt and indifference we funnel into our jails won’t eventually break out and destroy our community.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.