Hezbollah warlord was an enigma

- Share via

BEIRUT — In Hezbollah’s inner circle they called him “The One Who Never Sleeps.”

Imad Mughniyah was one of the most hunted men in the world. Western security forces spent 25 years pursuing the Hezbollah warlord, the alleged mastermind of infamous attacks of the late 20th century and a pioneer of brutal tactics later emulated by Al Qaeda. In fact, he may have proved a more disciplined, effective master of asymmetric warfare than even Osama bin Laden.

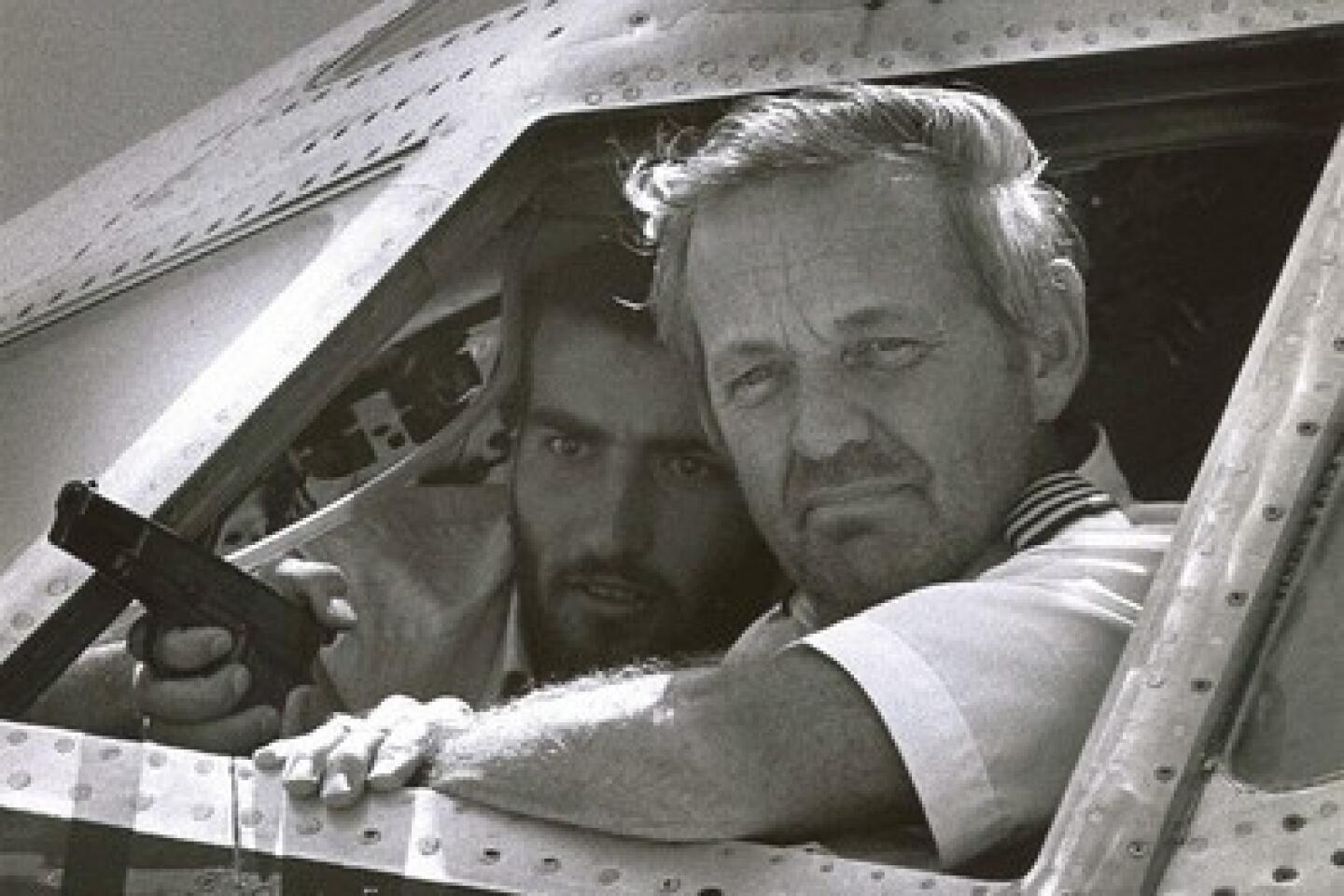

Mughniyah survived through anonymity: changing hide-outs, moving without bodyguards or drivers, a pistol always in his belt. On the evening of Feb. 12, he left a safe house in the Kfar Soussa neighborhood of Damascus, a warren of nearly identical towers that house the employees and headquarters of Syria’s vast intelligence apparatus.

He had just held a sit-down with a Syrian spy chief and was preparing for a secret meeting that night with President Bashar Assad, Western anti-terrorism officials say.

Seconds after Mughniyah got behind the wheel of his sport utility vehicle, an explosion incinerated him. The assassination in the heart of an authoritarian state ended his bloody odyssey through the modern history of terrorism.

His death at 45 remains as mysterious as his life. Interviews with anti-terrorism officials, diplomats and his associates reveal new details about the exploits of this secretive figure -- and about a slaying that may have been an inside job.

Mughniyah’s role at the hub of a murky alliance of Hezbollah, Syria and Iran made him powerful but vulnerable, officials say. The likeliest scenario is that Israel eliminated him. But the aftermath has reinforced signs of potential Syrian involvement and exposed tensions among Syria, Iran and Hezbollah, Western officials say.

“What’s troubling is that even if it was the Israelis, it happened in Damascus in a safe area meters from the office of [intelligence] chief Assef Shawkat,” said a Western diplomat in the Syrian capital.

Iran and Hezbollah have sworn revenge, putting Israel on worldwide alert for the kind of attacks that were once Mughniyah’s trademark.

Mughniyah sounded self-effacing in a rare interview he gave to a pro-Hezbollah newspaper not long before his death and published afterward.

“The Americans are making up stories about me and hold me responsible for a lot of attacks against them that happened around the world,” he told Ibrahim al Amine of Lebanon’s Al Akhbar. “Sometimes they think of me as if I have the key to the universe. It is difficult for them to understand that I am part of an institution that patiently plans and designs its moves.”

Mughniyah had grown pudgy, his beard graying beneath round-rimmed glasses. He lived on the run among Iran, Syria and Lebanon and had two wives: a Lebanese in southern Lebanon and an Iranian in Damascus. He drove his own car, bought groceries alone and took catnaps while working nonstop, associates said. An associate in Damascus recalled how, during a heated group discussion, he curled up on a couch and went to sleep.

He oversaw foreign networks that he built after his terrorism campaign in Lebanon, including the 1983 bombings of the U.S. Embassy and Marine barracks. His cells allegedly carried out operations in France and Argentina, where two car bombings of Jewish targets left more than 100 dead. He also met in Sudan in the early 1990s with Osama bin Laden, whose militants got explosives training from Hezbollah experts.

Pursued by Israeli and U.S. forces, Mughniyah eluded several assassination attempts. His brother died in one attack in 1994; Mughniyah’s bulletproof vest took multiple hits in another ambush.

In the late 1990s, Hezbollah curtailed attacks outside the Middle East. Mughniyah was an architect of a shift to concentrate on political and military activity in Lebanon. He served on the shura, the militia’s leadership council, after being elected in 2001 under the alias Jawad Nur A-Din, Western officials say.

His post was secret, officials say, because Hezbollah claims to separate its political activity from its military wing, which is designated as a terrorist group by the United States and Israel.

Mughniyah’s duties included aiding Palestinian militant groups with training and arms procurement, and running security for Hezbollah leader Sheik Hassan Nasrallah, to whom he was close, experts and associates say.

On May 13, 2006, he met in Lebanon with Hassan Zarkani, a representative of Iraqi Shiite strongman Muqtada Sadr, and agreed to provide smuggled anti-tank missiles to Iraqi fighters and train them in their use, Western anti-terrorism officials say.

But his prime obsession was the destruction of Israel. Hezbollah insiders and Israeli officials say that during the 2006 war in Lebanon, he ordered battlefield tactics that surprised Israeli troops with their ferocity and effectiveness.

“We saw death in their eyes,” Mughniyah said of the Israelis, whose fighting skills he admired, according to Lebanese journalist Amine.

Although exhausted to the point of illness by the war, Mughniyah worked with Iran and Syria to rearm Hezbollah, associates and Western anti-terrorism officials say. He was uniquely placed in that triumvirate because of close ties to Iran, particularly the Revolutionary Guard. But the fact that he answered to multiple masters may have been his undoing.

Despite official claims, Syrian leaders knew he was in Damascus in February, Western officials say. During visits to the Syrian capital, he stayed in a building owned by a business partner of Rami Makhlouf, a cousin of Assad, officials say. The meeting in Kfar Soussa took place at a safe house used by Syrian intelligence near a well-guarded Iranian school, an area where Syrian spies work and live, officials say.

Mughniyah met with Shawkat, the chief of military security, and Mohammed Nasif Kheirbek, a special assistant to the vice president, the officials said. The discussion, centered on political conflict in Lebanon, was a prelude to a clandestine late-night appointment with Assad at the presidential palace, the officials say, citing intelligence from a source in Syria.

“Mughniyah had had a busy day,” a Western anti-terrorism official said. “And he was heading to meet Assad when he was killed.”

Syrian officials declined to comment. But the aftermath offered a rare look at apparent tensions among Syria, Iran and Hezbollah. Syria’s deputy foreign minister popped up in Tehran. Iran’s foreign minister announced a joint investigation. One of Mughniyah’s widows denounced the Syrians as “traitors,” suggesting that they had a hand in the killing, then retracted the remark.

Finally, the Syrians said they would investigate. But they let an April deadline pass without comment on the inquiry. And Shawkat, a once-powerful ally of Iran, was excluded from the investigation, Western officials say.

Syria’s behavior contrasted dramatically with the threats against Israel by Iran and Hezbollah. The government in Damascus has entered indirect peace talks with Israel and kept a tight lid on the investigation.

Some believe that Syrian leaders played a role in Mughniyah’s demise, perhaps as part of a deal with the West. The scenario of an assassination by the Israelis does not rule out Syrian involvement, a Western security official said.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the death of Mughniyah was part of an internal struggle,” said the official, who asked not to be identified because he does not speak publicly.

Why would Syria want to get rid of Mughniyah? One theory is that the U.S. and Israel exerted pressure on Damascus. They had leverage: an international court’s pending investigation of Syrian leaders in the killing of Lebanese leader Rafik Hariri in 2005. Assad’s innermost circle may have decided to accept a hit on Mughniyah in exchange for protection from indictments and for improved relations with the West, officials and experts say.

A simpler theory: Mughniyah somehow crossed his Syrian patrons and paid for it.

“Syria is very pragmatic,” said a diplomat in Damascus. “If you have to eliminate someone, you do it.”

But other experts doubt that Syria sacrificed an ally of such stature. An Israeli airstrike on an alleged nuclear site last year suggests that the Israelis “operate on their own with great effectiveness inside Syria,” a senior European anti-terrorism official said.

Israel does not confirm or deny having a role in the death. Iran and Hezbollah face a strategic dilemma, experts say. A rash move against Israel could bring foreign condemnation, even military action. And Iran must consider the potential effect on high-stakes talks over its nuclear program.

“Hezbollah can strike all over,” an Israeli security official said. “But they need an Iranian Embassy for support. It has been more than 10 years since they did something like that. They will have to consider if they want to go back to that era. If they do it now, we will hit them hard.”

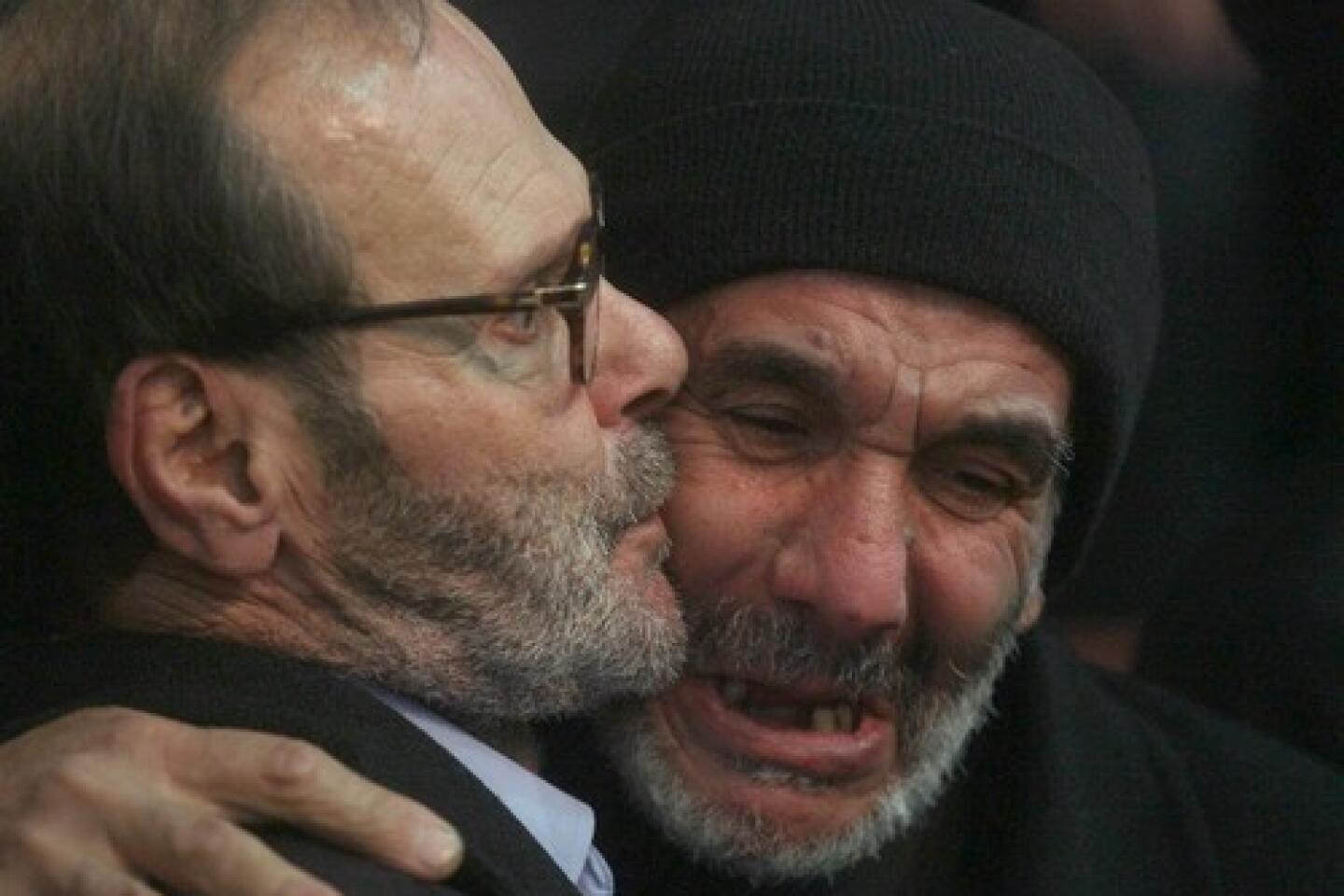

In south Beirut, meanwhile, a shrine draws mourners at all hours. The enclosure resembles a large outdoor restaurant assembled with cheap materials from a garden or hardware shop. Plastic flowers decorate a tomb at the center of a plot of artificial grass that covers the graves of about 100 fighters, adorned with small glass cases holding photos and other mementos.

On a recent afternoon, a bare-headed woman in a hot-pink shirt entered and knelt at the tomb. She touched it gently, then got up and left the place where Mughniyah finally sleeps.

Special correspondents Ziad Haydar in Damascus and Ramin Mostaghim in Tehran contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.